Parkinson’s Mice Show Gains From Exercise, Cholesterol Medication

Mice in a treadmill program showed a significantly reduced loss of dopamine-producing neurons

Written by |

Regular treadmill exercise significantly reduced the aggregation and spread of alpha-synuclein in the brain — a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease — prevented neurodegeneration, and lessened motor deficits in a mouse model of Parkinson’s, a study showed.

These benefits were found to be associated with the activation of a receptor protein called peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha) in the brain. The receptor is known to activate genes that promote growth, maturation, and survival of dopaminergic neurons, which are progressively lost in Parkinson’s disease.

Also, fenofibrate, a medication typically used to lower cholesterol and other fatty molecules in the blood and is known to activate PPAR-alpha, resulted in similar benefits to treadmill exercise in the mouse model.

These findings suggest regular exercise on a treadmill or PPAR-alpha-activating medications such as fenofibrate may have beneficial effects in people with Parkinson’s, the researchers noted.

“We’re very excited about the results,” Kalipada Pahan, PhD, the study’s senior author and a professor of neurological sciences, biochemistry, pharmacology at the RUSH University Medical Center, Illinois, said in a university news release.

“Our hope is that we can use this as a jumping off point for furthering our ability to help Parkinson’s patients manage their symptoms,” Pahan, who is also the Floyd A. Davis endowed chair in neurology at RUSH, said.

The study, “Treadmill exercise reduces α-synuclein spreading via PPARα,” was published in Cell Reports.

Several neurodegenerative diseases are associated with the abnormal, toxic accumulation and spread of aggregates of a protein called alpha-synuclein in the brain and spinal cord. Known as alpha-synucleinopathies, these conditions include Parkinson’s, Lewy body dementia (LBD), and multiple system atrophy (MSA).

“However, until now, no effective therapy has been available to prevent [alpha-synuclein] spreading in human brains of [alpha-synucleinopathies],” the researchers wrote.

Increasing evidence supports a link between physical activity and brain health, with regular exercise helping to delay brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s.

Phase 2 trial data also showed high-intensity treadmill training was more effective at preventing motor function worsening in Parkinson’s patients than a moderate-intensity program. A Phase 3 trial, called SPARX3 (NCT04284436), is now confirming these findings. Enrollment remains open at sites in North America.

Pahan and his team looked at the effects of regular treadmill exercise in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease that produces A53T, a mutant form of alpha-synuclein known to form clumps. These mice are known to develop significant neuron-specific alpha-synuclein aggregation and motor impairments starting from 7 to 8 months of age.

The researchers first analyzed mice with early alpha-synuclein aggregation due to the injection of preformed fibrils (PFF) of the protein in the animals’ brain at 2 months old.

Two months after, the mice were subjected to treadmill exercise six days a week for two months. Exercise sessions lasted 30 minutes and involved an increase in speed over the two months.

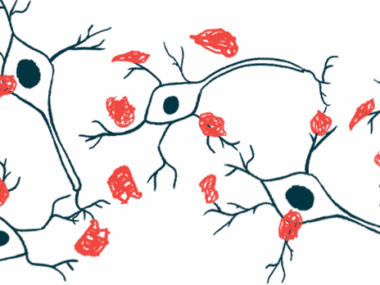

Results showed regular treadmill exercise significantly reduced not only alpha-synuclein aggregation, but also its spread through the brain in these mice, relative to no exercise program.

Mice undergoing the treadmill program also showed a significantly reduced loss of dopaminergic, or dopamine-producing, neurons, and of dopamine and its byproducts. Dopamine is a major chemical messenger in the brain and its loss leads to Parkinson’s characteristic motor and non-motor symptoms.

Treadmill training was also associated with a nearly complete reversal of motor deficits in these animals, further supporting its ability to reduce both molecular hallmarks of the disease and its clinical symptoms.

Similar results were obtained in non-PFF-injected A53T mice (aged 8 months) with treadmill exercise being additionally linked to a restoration of spatial memory.

“Treadmill exercise may be beneficial in patients with PD, MSA, and DLB,” the researchers wrote.

Pahan added that “understanding how the treadmill helps the brain is important to developing treadmill-associated drugs that can inhibit [alpha-synuclein-associated damage], protect the brain, and stop the progression of Lewy body diseases.”

Further analyses showed the exercise program’s beneficial effects were associated with the activation of PPAR-alpha in dopaminergic neurons, which was impaired in the mouse model.

This receptor protein is known to activate genes involved not only in these neurons’ survival, but also in the degradation of protein aggregates, which is deficient in almost all forms of alpha-synucleinopathies.

In agreement, the researchers detected significant increases in the levels of molecules involved in protein clumps’ breakdown and recycling, such as TFEB, a master regulator of these processes.

The team then evaluated whether PPAR-alpha activation alone was sufficient to suppress alpha-synuclein aggregation and spreading.

They treated the PFF-injected mice with fenofibrate, a known activator of PPAR-alpha. The medication is sold as Triglide, Antara, and other brand names to treat higher than normal blood levels of fatty molecules.

One month of daily treatment with fenofibrate resulted in benefits similar to those of two months of regular treadmill exercise.

“Collectively, these findings clearly state that activation of [PPAR-alpha] solely by its agonist fenofibrate is sufficient to reduce [alpha-synuclein-associated disease] and attenuate parkinsonian features in mice,” the researchers wrote.

“If taking fenofibrate can replicate the same effects of running on a treadmill then it would be a notable advance in the treatment of these devastating neurological disorders,” Pahan said.

Notably, FHL-301, a PPAR-alpha activator, is being developed by Forest Hills Lab for Parkinson’s. It was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last year for testing in a Phase 2 clinical trial.