FAQs about Parkinson's disease diagnosis

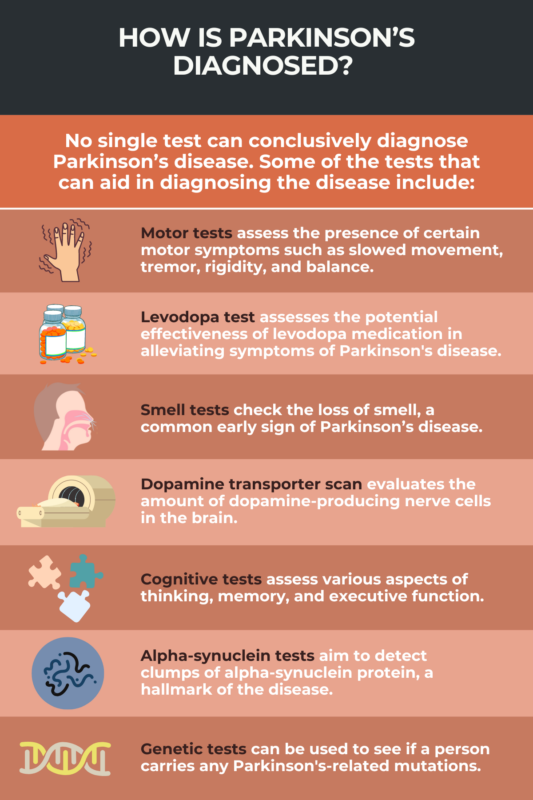

No test can confirm a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Instead, a Parkinson’s diagnosis is established by a clinician examining a patient’s symptoms, especially his motor symptoms. Tests to look for common signs of Parkinson’s and to rule out other explanations for them aren’t required, but can help support a diagnosis.

Parkinson’s disease is typically diagnosed by a neurologist, who specializes in disorders that affect the brain and nervous system.

Typically a person will be evaluated for Parkinson’s disease if they are having symptoms that indicate the disorder, such as slowed movements, tremor, and/or rigidity.

To confirm a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, a patient must have bradykinesia (slowed movement) and at least one other motor symptom, such as tremor, rigidity, or problems with balance. The diagnosis can be made once these symptoms are established and other potential causes have been ruled out. Most people with Parkinson’s notice their first symptoms when they are 60 or older, but in about 10-20% of cases, Parkinson’s can be diagnosed before a person turns 50, where it’s called early-onset Parkinson’s.

Since diagnosing Parkinson’s requires testing for disease-typical symptoms and ruling out other possible causes for symptoms, confirming Parkinson’s usually takes some time. Studies suggest most people are diagnosed within the first six months after seeking medical attention for Parkinson’s-like symptoms, but it’s not uncommon to go up to about three years before a diagnosis is confirmed.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by