Heart PET scans help to spot Parkinson’s years before symptoms

At-risk group with cardiac marker later develop disease or Lewy body dementia

Written by |

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans of the heart can help to identify people, known to be at risk for Parkinson’s disease or Lewy body dementia, up to seven years before they go on to develop these disorders, a small study suggests.

In the National Institutes of Health (NIH) study, the loss of norepinephrine in the heart preceded a loss of dopamine in the brain and the onset of Parkinson’s symptoms or those of Lewy body dementia. Norepinephrine is a signaling molecule derived from the dopamine, the chemical messenger lost to patients.

Symptoms often occur after considerable damage has been done to the brain’s dopamine-producing neurons (nerve cells). Diagnosing Parkinson’s before symptoms are evident can allow for interventions, from lifestyle and dietary changes to medications, to start early, when they are likely to be most effective.

The study, “Cardiac noradrenergic deficiency revealed by 18F-dopamine positron emission tomography identifies preclinical central Lewy body diseases,” was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Study into an early Parkinson’s disease diagnosis in people with risk factors

“Once symptoms begin, most of the damage has already been done,” David S. Goldstein, MD, PhD, principal investigator at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the NIH, said in an institute release. “You want to be able to detect the disease early on.”

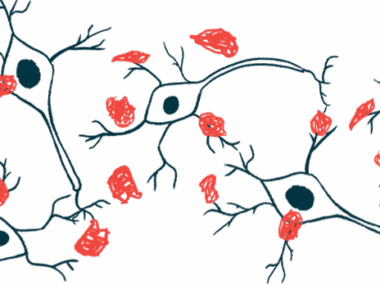

Both Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia are caused by abnormal clumps of the protein alpha-synuclein, known as Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies are toxic to neurons, and are able to spread from one neuron to the next, driving progressive damage.

Earlier work by Goldstein and others showed that alpha-synuclein clumps build in neurons that supply the gut, skin, and glands, affecting the autonomic nervous system that regulates involuntary body processes, such as heart rate and blood pressure.

Goldstein also knew that people with Lewy body diseases, including Parkinson’s, have a severe lack of cardiac norepinephrine, which normally is stored and released by nerves that supply the heart.

“Although it is widely suspected that the pathogenetic process leading to PD [Parkinson’s disease] can begin outside the brain, with early involvement of the autonomic nervous system, to date this key issue has not been addressed directly in a prospective, long-term follow-up study,” the researchers noted.

In the PDRisk study (NCT00775853), a biomarker study for people with a known disease risk, Goldstein’s team used the 18F-dopamine PET tracer, whose signal parallels the level of norepinephrine in the heart, to determine if it could identify those who years later develop Parkinson’s or Lewy body dementia.

18F-dopamine PET scans were given to 34 people every 18 months at the NIH Clinical Center, continuing for about 7.5 years or until a disease diagnosis.

All participants had three or more Parkinson’s risk factors. These include a family history of the disease; a loss of the sense of smell, a common Parkinson’s nonmotor symptom; dream enactment behavior, a sleep condition in which people act out their dreams and can precede the disease; and low blood pressure or orthostatic intolerance, such as lightheadedness upon standing.

Eight of nine people with initial low signal go on to develop disease

Nine had an initial low 18F-dopamine signal in their first PET scan of the heart, while the 25 others had a signal within the normal range. At seven years of follow-up, disease developed in eight of those with a low signal and in one person with a normal initial signal, but that signal was low at diagnosis, the researchers noted.

Among these nine people, 26% of the total study group, six went on to develop Parkinson’s, two developed Lewy body dementia, and one developed Parkinson’s with dementia. This is “a larger percentage than would be expected in the general population,” the scientists wrote.

While the study included a small number of participants, “cardiac [heart] 18F-dopamine PET highly efficiently distinguishes at-risk individuals who are diagnosed subsequently with a central LBD [Lewy body disease] from those who are not,” the researchers concluded.

“Low 18F-dopamine-derived radioactivity increased to a virtual certainty the likelihood of developing a central LBD,” while a normal signaling “decreased to near zero the likelihood of a subsequent central LBD, despite the same risk factors,” they added.

“The loss of norepinephrine in the heart predicts and precedes the loss of dopamine in the brain in Lewy body diseases,” Goldstein said. “If you could salvage the dopamine terminals that are sick but not yet dead, then you might be able to prolong the time before the person shows symptoms.”