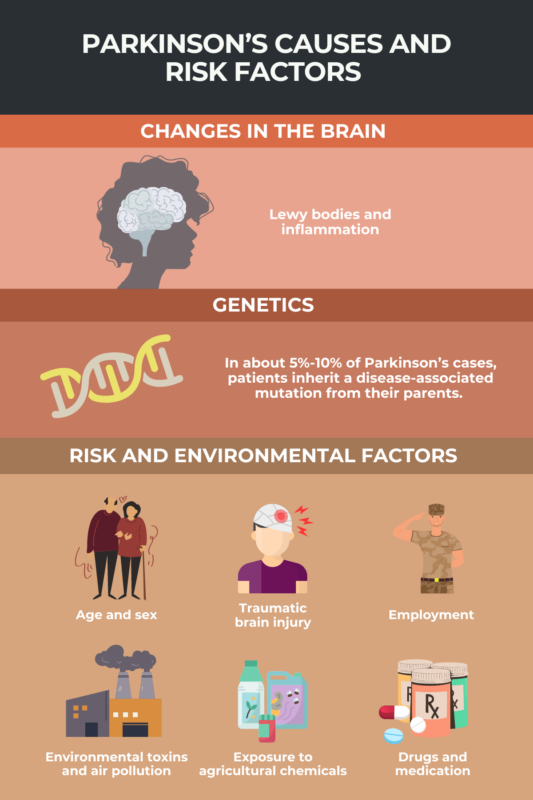

FAQs about Parkinson’s disease causes

In about 5% to 10% of cases, Parkinson’s disease is caused by a genetic mutation. However, most cases of Parkinson’s are not associated with a known genetic cause.

In the vast majority of Parkinson’s disease cases, there is no clear cause. The condition is thought to result from a combination of genetic changes and environmental factors that lead to the progressive dysfunction and death of neurons responsible for producing the neurotransmitter dopamine, called dopaminergic neurons, which ultimately causes the disease’s symptoms.

Parkinson’s disease most frequently occurs in adults age 60 and older, and it is roughly twice as common in men than in women. People with a family history of the disease also may be at increased risk.

The risk of Parkinson’s disease may be higher in people who have been exposed to certain chemicals — such as trichloroethylene (TCE) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) — toxins, heavy metals, pesticides and herbicides, and air pollution. People with a history of traumatic brain injury are also at increased risk of developing the disease.

Men are about twice as likely to get Parkinson’s compared with women. However, women tend to have a faster disease progression.

Fact-checked by

Fact-checked by