Gut Microbes Linked to Progression of Neurodegenerative Disorders, Study Finds

Microorganisms living in the gut can influence the progression of neurodegenerative diseases through two types of brain cells, and understanding more about how they suppress inflammation could lead to new therapies for diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s, a study found.

The research, “Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites,” was published in the journal Nature.

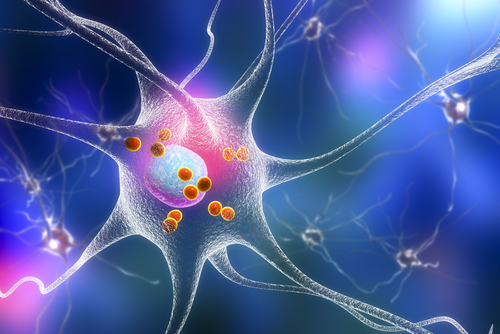

Scientists from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) addressed the influence of gut microbes on two types of central nervous system cells that play key roles in inflammation and degeneration – microglia and astrocytes.

Microglia are the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, or CNS, responsible for clearing cellular debris, plaques, and dead neurons. However, microglia can also release molecules with toxic effects on astrocytes, a cell type with various functions including the formation of the blood-brain barrier and response to injury.

Damaged astrocytes are thought to contribute to MS development and that of other neurologic diseases, including Parkinson’s.

Brigham researchers have previously explored the gut-brain connection to gain insights into MS. Some studies have examined how byproducts from organisms in the gut may promote brain inflammation, but this study is the first to report on how microbial products may act directly on microglia to prevent inflammation.

Using a mouse model of MS called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the team found that microglia release two types of proteins that regulate astrocytes and disease development: TGF-alpha and VEGF-B.

While TGF-alpha limits astrocytes’ detrimental effects and prevents EAE development, VEGF-B has the opposite effect.

Experiments performed in brain samples of humans with MS showed that TGF-alpha and VEGF-B mediate microglia’s regulation of astrocytes and that production of these two proteins correlates with MS lesion stage.

Researchers found that metabolites derived from microbes’ break down of tryptophan – an amino acid, or the building block of proteins, found in turkey, eggs, and salmon – may limit inflammation in the CNS through influence on microglia and regulation of gene expression in astrocytes.

The compounds may cross the blood-brain barrier — a semipermeable membrane that separates brain blood vessels from outside fluid — and ease inflammation and degeneration in the brain.

“These findings define a pathway through which microbial metabolites limit pathogenic activities of microglia and astrocytes, and suppress CNS inflammation,” researchers wrote.

“Now that we have an idea of the players involved, we can begin to go after them to develop new therapies,” Francisco Quintana, PhD, the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

This molecular pathway has recently been linked to Alzheimer’s and glioblastoma. Researchers at BWH are looking at small molecules and probiotics to identify additional elements that participate in the pathway, which could lead to therapy advances in Parkinson’s, MS, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The insights gained from the study could guide researchers toward new therapies for neurodegenerative diseases, Quintana said.