Exploring the Potential of a Brain Therapy Model for Parkinson’s

Written by |

For my PhD research, I wanted to examine in more detail the processes by which humans move from traumatic injury, like traumatic brain injury, to a place of well-being. My clinical experience led me to consider two things that people drew upon.

I found that, firstly, they drew upon cognitive processes when recovering from trauma. Secondly, the recovery process was helped by the relationship between the injured and those who are deemed healing practitioners. I witnessed a special kind of relationship that directly affects healing.

It is this healing relationship that became the focal point for my PhD. But I never let go of my deep belief in neural plasticity and our ability to cultivate our own neural sprouting. Little did I know then that I’d be applying healthy doses of brain therapy fertilizer to my own neural branches in fighting the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s is complex in presentation, and it’s difficult to find a set of symptoms along with their progression that fits anything more than about half of the disease population. It’s been frustrating trying to advance my own cerebral rehab in the face of unclear guidelines. Whatever brain activities I choose each day are going to affect my brain health. To decide which brain activities are best, I need some clear brain therapy guidelines.

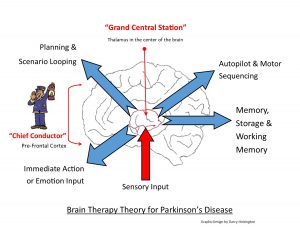

In my columns, I’ve written about creating a wellness map. This is a metaphor for brain therapy. Much of what I have written is tied to a brain model based on functional neuroanatomy — the connections between the prefrontal cortex and the thalamus. This relationship is illustrated in the following graphic:

The graphic shows a “Grand Central Station” where sensory stimulus input comes in and gets routed back out to the appropriate destination. There are several “most popular” destinations: motor sequencing autopilot, making and carrying out plans, short-term and long-term memory, and actions or thoughts that are deemed to need more immediate attention, which often are emotion-laden.

Overseeing all of this is the open “conductor.” The conductor’s main responsibility is to make sure that the most important things get onto the tracks leaving the station before the less important things. The theory proposed here is that scenario-looping breakdowns, a malfunctioning autopilot, and exaggerated stimuli input are happening with information coming out of the station. This is information that got on the tracks without conductor intervention.

This theory proposes that these “conductor-Grand Central Station malfunctions” are major contributors to Parkinson’s symptoms. If we can decrease the effects of scenario-looping breakdowns, the malfunctioning autopilot, and exaggerated emotional stimuli, then the effects of Parkinson’s disease should be reduced.

The second part of this theory states that the conductor is still able to direct traffic out of the station. In addition to this, neural plasticity is a process that’s still available in the senior years of life, albeit more slowly. The conductor resides in the front part of our brain (frontal lobe) and is often referred to as “executive functioning.” I think that this term is too broad and lacks the specificity needed for me to design brain therapy. The success of my personal brain rehabilitation depends on my success with training the conductor. This is one of those frontiers of the exploration of wisdom.

I had been hesitant about putting such an immature theory into the public domain, but I was encouraged by a few short paragraphs in neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi’s book, “When Breath Becomes Air.” He describes performing deep brain stimulation (DBS) on a Parkinson’s patient. In the middle of the procedure, the doctor needed to shift the electrode a few millimeters within the thalamus. The patient was complaining of intense mood surges that had no connection to context, but a small shift of the electric stimulus provided relief.

What intrigued me was that the stimulation of the thalamus triggered surges of exaggerated mood that had no link to the context. I’ve termed them SEM (surges of exaggerated mood) attacks. It was exciting to discover that a tiny shift in the electrode was all that was needed and — poof! — emotions were stable and tremor was reduced. I thought, “Perhaps I can train my brain to do its own natural version of DBS?”

I am just beginning this journey and would appreciate any thoughts. I look forward to hearing from you in the comments below.

***

Note: Parkinson’s News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Parkinson’s News Today or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to Parkinson’s disease.

Learner1

I'd be very interested in your thoughts on hyperbaric oxygen therapy as well as the recent article on mitochondrial correction by Thomas Seyfried, Dominic D'agostino, and Garth Nicolson, as well as the use of supplements like curcumin, boswellia, and glutathione.

Holden Hohaia

Really interesting article. I find if I focus on calming my emotions during tremor inducing situations (eg public speaking) I can generally get through most situations. It's a balance though because you need some emotional content say, for example, when you're public speaking or engaging in a group conversation. Is the key to perhaps try and stay relaxed emotionally no matter what? PS I was diagnosed about a year ago.

Dr. C

Hi Holden ~ Thanks for the comment. In the early stages of Parkinson's one might experience subtle changes in emotional control while others experience major disruptions. I share some insights on threshold management in my columns. There will be good days, bad days and ugly days. The key, I think, is to recognize the early signs of emotional lability and manage those early signs. It may become more challenging as the disease progresses.

I hope you continue to read my columns and those of the other PD columnists and share your experiences and insights with the PD community through BioNews Today.

Dr. C.

Michael skyn

A promising brain therapy model for Parkinson’s aims to restore neural function by targeting damaged dopamine pathways. Techniques like deep brain stimulation, gene therapy, and neuroplasticity-based Rosecrans Care Center Gardena CA treatments offer hope for slowing disease progression. By enhancing brain connectivity and reducing symptoms, these innovations could significantly improve mobility, cognition, and quality of life for Parkinson’s patients.