Molecule Protected Dopamine Neurons in Mice with Parkinson’s

Written by |

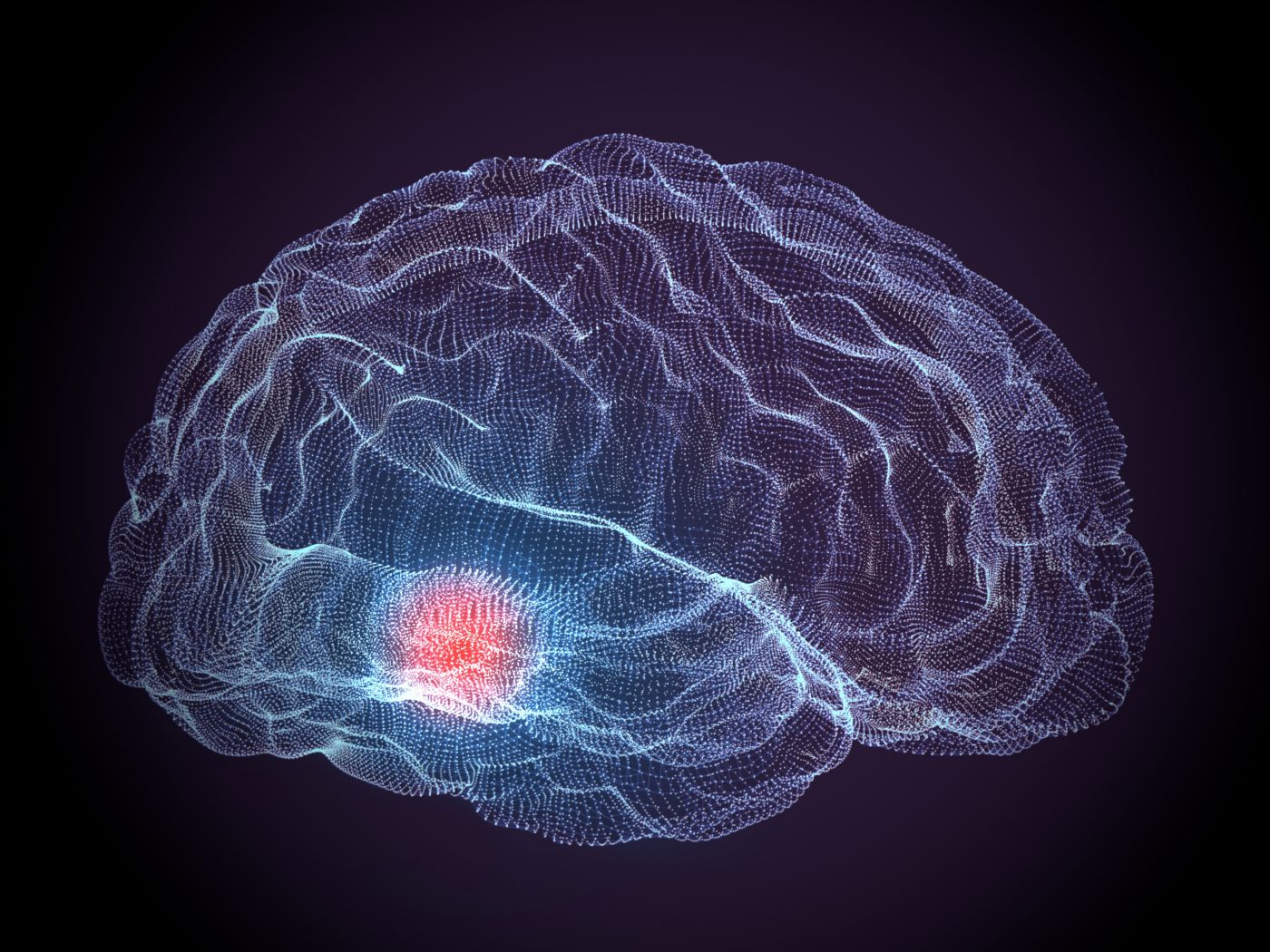

Administering a naturally occurring growth factor to a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease reduced inflammation and prevented neurons from dying, suggesting that such factors have the potential to stop or slow the progression of disease.

The study, “Activin A Inhibits MPTP and LPS-Induced Increases in Inflammatory Cell Populations and Loss of Dopamine Neurons in the Mouse Midbrain In Vivo,” supports the idea that growth factors may be beneficial in neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s. The work was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Since Parkinson’s disease is usually not discovered until symptoms start showing — and a large portion of the dopamine-producing neurons are already gone — researchers are trying to find ways to prevent the rest of the neurons from the same fate.

One idea is to use naturally occurring growth factors. Researchers at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia discovered that one such molecule, known as activin A, protects dopamine neurons from death in mice.

They tested the factor in mice exposed to two different treatments that cause the death of dopamine neurons. In both cases, activin A protected dopamine and other types of neurons from further damage.

“Despite decades of research, the underlying causes of Parkinson’s remain unknown and the most effective treatment is only symptomatic and comes with its own set of complications over time,” Bryce Vissel, a professor of neuroscience and senior author of the study, said in a press release.

“We’ve taken activin A, a growth factor that occurs naturally in the body, applied it into the brains of mice in laboratory tests and found exciting beneficial effects.”

One of the key findings was that the growth factor lowered the brain inflammation in the mice. According to Vissel, this provides additional proof that inflammation contributes to driving the development of Parkinson’s.

“This study shows that activin A can slow loss of dopamine nerve cells, providing a possible approach to slowing the disease,” Vissel said. “An exciting aspect of our previous research is that we’ve shown the activin A molecule has the potential to trigger regeneration in the nervous system. It raises the question as to whether this could lead to a treatment that could also repair the damaged brain areas in Parkinson’s disease.”

The research is still in early stages and there are some aspects the team does not understand. In Parkinson’s disease, dopamine neurons in a tiny area of the brain called the substantia nigra die first. This leads to the loss of dopamine and dopamine neurons in another region, the striatum, which controls movement. The study showed that while activin A prevented the death of nerve cells in the substantia nigra, it didn’t protect them in the striatum.

“Our goal is to try to slow down or halt further degeneration in the brain by protecting the surviving neurons,” said Dr. Sandy Stayte, the study’s first author and a neuroscientist who has been studying Parkinson’s disease with Vissel for nearly a decade.

For such an approach to be as effective as possible, it is necessary to identify the disease before movement symptoms start appearing. There is currently plenty of research that aims to find markers of the disease that are measurable at earlier stages.

“There is a much higher chance of being able to deliver a therapeutic strategy that will halt the cell death process if we can identify the disease earlier,” Stayte said.