Worse GI Symptoms Predict Anxiety, Depression, and Vice-versa

Written by |

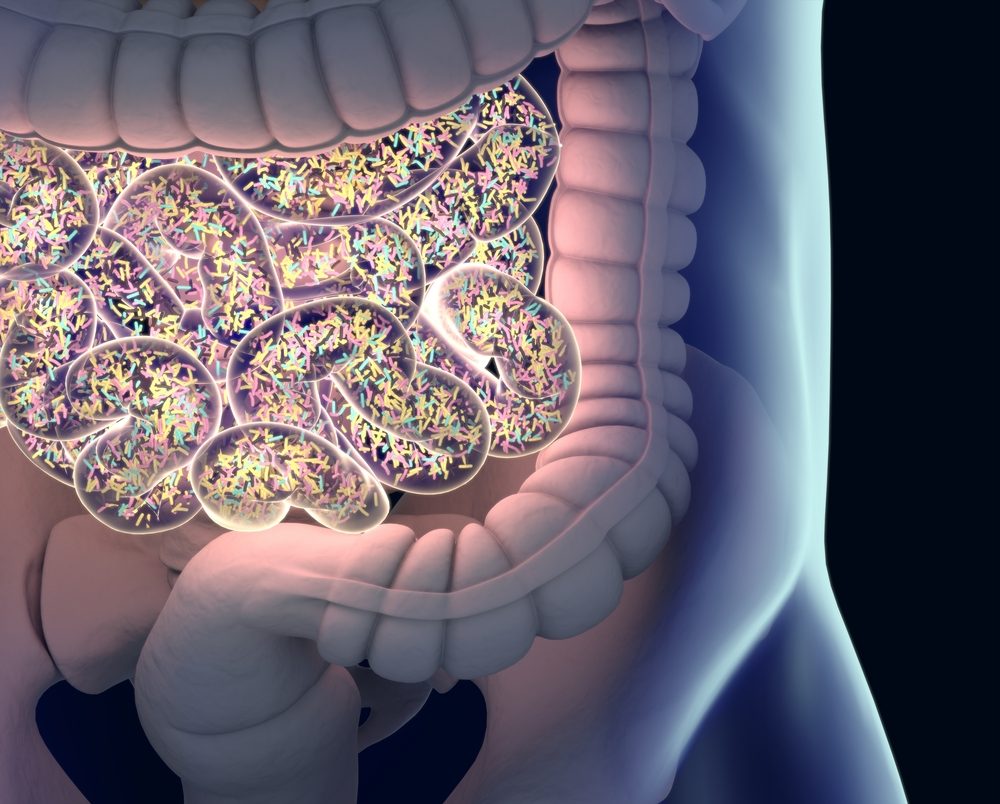

Anatomy Image/Shutterstock

Worse gastrointestinal symptoms predict more severe anxiety and depression, and vice-versa, within the same year and in the following year in people with Parkinson’s disease, a study shows.

This bidirectional link between gut and mental health suggests a potential cyclical relationship, in which gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms increase the risk of worsening mood symptoms, and exacerbated mood symptoms, in turn, increase the chances of worsening GI problems, according to the researchers.

These findings add to the increasing body of evidence highlighting the importance of the gut-brain axis in several neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s. Indeed, this team of scientists had previously shown that constipation among newly diagnosed Parkinson’s patients was a risk factor for future cognitive decline.

Further research may help pinpoint the underlying mechanisms behind the gut-brain axis and subsequently identify new therapeutic approaches, the researchers said.

The study, “A bidirectional relationship between anxiety, depression and gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson’s disease,” was published in the journal Clinical Parkinsonism & Related Disorders.

Besides its well-known motor symptoms, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by non-motor symptoms such as gastrointestinal problems, cognitive impairment, anxiety, and depression.

These non-motor problems may occur years before the onset of motor symptoms, studies have found, with research suggesting that the disruption of gut microbiota “contributes to the progression of a variety of motor and non-motor symptoms,” the investigators wrote.

Gut microbiota comprises the vast community of friendly bacteria, fungi, and viruses that colonize the gastrointestinal tract. This community helps to maintain a balanced gut function and protect against disease-causing organisms. It also influences the host’s immune system and inflammatory responses.

Additionally, “there is evidence of a bidirectional association between mental health and gut health among individuals with GI disorders,” the researchers wrote.

However, whether this is the case in Parkinson’s disease remains unclear.

Now, a team of researchers in the U.S. evaluated the longitudinal (over time) and directional associations between GI symptoms and anxiety and depression among 487 people newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s. These new patients were followed for up to five years within the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI), an observational study designed to collect and catalog as much information as possible on Parkinson’s and its various features over an individual’s lifetime.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the results of validated questionnaires on anxiety, depression, and gastrointestinal symptoms completed by the patients at each annual visit. Motor symptom severity was assessed with the Unified Disease Rating Scale – Part III.

The patients’ mean age was 61.1 years, 94.9% were Caucasian, and 65.1% were men. They generally reported minimal to mild symptoms of anxiety and depression, but 35.9% were classified as clinically depressed during at least one visit during the five-year study period.

The results showed that both anxiety and depression were predicted by both current and past year gastrointestinal symptoms. Specifically, more severe GI symptoms were significantly associated with worse anxiety and depression in the same year and in the subsequent year.

Fewer years of education, and more severe motor symptoms, also significantly predicted more severe anxiety and depression. Meanwhile, younger age was significantly associated with worse anxiety only.

The researchers also found evidence of the inverse relationship, with more severe anxiety and depression significantly predicting worse GI symptoms concurrently and in the following year.

Notably, older age, male gender, more severe motor symptoms, and gastrointestinal symptoms becoming more frequent over time also were risk factors of more severe GI symptoms.

These findings suggest that gastrointestinal problems and anxiety/depression are bidirectional risk factors — meaning each one is a risk factor for the other — for people living with Parkinson’s.

Preliminary evidence also pointed to a cyclical relationship between gut health and mental health in Parkinson’s, “where GI symptoms increase an individual’s risk for worsening mood symptoms, which subsequently increase their risk for worsening GI symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

The fact that depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s patients are associated with markers of inflammation, which in turn were shown to be linked to gut microbiota parameters, further support the hypothesis that this link between gut and mental health is mediated by bidirectional communication along the gut-brain axis, according to the researchers.

Further studies involving measures of microbiota composition and function are needed to clarify whether the gut-brain axis plays a mechanistic role in Parkinson’s, not only in early disease, but also in late-stage patients, who also more often have clinical depression and/or anxiety.

New data may help to identify new avenues of treatment for helping patients, the researchers said.

“Knowledge of mechanisms underlying the association between gut/immune health and mental health may potentially play an important role in detecting and treating mental health disorders in [Parkinsons’s],” the team wrote.

Increasing interest has focused on potential therapeutic approaches based on changes in the gut microbiota to improve mental health and reduce mood symptoms in diseases such as Parkinson’s.