Motor imagery impaired in Parkinson’s patients, study finds

Disease changes how people imagine movements for more affected body side

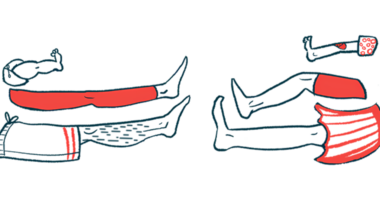

Besides motor challenges, people with Parkinson’s disease have difficulty with motor imagery, or generating a mental representation of a movement, a study showed. That’s particularly true for the more affected side of the body.

“Even when people with Parkinson’s think about movement, it’s different for their more affected side,” Kathryn Lambert, the study’s first author and a PhD candidate at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, said in a university news story. “If someone is perceiving their movement wrong, it can actually be quite dangerous,” increasing the risk of falling or tripping, Lambert said.

Rehabilitation interventions addressing motor imagery issues, such as providing visual information and other cues, may help ease movement difficulties, the researchers noted.

The study, “The lateralized effects of Parkinson’s Disease on motor imagery: Evidence from mental chronometry,” was published in Brain and Cognition.

Information to the brain

Parkinson’s is characterized by motor symptoms that include slowness of movements, muscle stiffness, tremors, and postural instability. These symptoms result from a dysfunction in the brain mechanisms that support the planning, coordination, and execution of voluntary movements.

All goal-directed movements start with a mental representation of the intended action, meaning that before a physical movement occurs, the brain compiles sensory information on the body’s position and envisions the steps needed to execute movements, a process called motor imagery.

“We do this really quickly and automatically,” Lambert said. “Then the brain takes that plan and transforms it into an action in our body.”

However, people with Parkinson’s may have deficits in proprioception (sense of body position) and kinesthesia (sense of body movement) that lead to disruptions in this process.

“If you have impairments in proprioception and kinesthesia, it may be a little harder to generate an accurate motor image in your head because you have less accurate information coming in from your senses,” Lambert said.

As Parkinson’s motor symptoms typically start in one side of the body, the researchers analyzed whether patients’ motor imagery was different when the task involved the most affected side versus the less affected side.

Thirty-eight Parkinson’s patients, with a mean age of 68.7, were recruited at several organizations and clinics in Canada. All were diagnosed at age 50 or older, and had been living with the disease for a mean of 5.2 years.

Most (76%) had tremors, 21% had postural instability, and all had more severe symptoms in one side of the body, most commonly in the dominant side. Nearly all were on dopaminergic medication, which continued during the study.

Results from a test assessing the time patients took to move 12 blocks from one box compartment to another showed that temporal accuracy — the sense of how long it takes to perform a movement — was different when the task was performed with the more affected versus less affected side of the body.

Participants were more likely to overestimate the speed of movements, and took longer to complete the task, when the task involved their more affected side.

“These results indicate that people with [Parkinson’s disease] imagine movements differently when the target actions their more affected versus less affected side,” the researchers wrote.

Therapy for cognitive processes

Poorer cognitive function, higher self-reported intensity of the imagined movement sensation, and lower self-reported clarity of the movement visual image predicted shorter mental, as opposed to physical, movement times for the more affected side alone.

Data suggested that “side-specific deficits in kinaesthesia and proprioception contribute to inaccurate mental representations of action characteristics” in people with Parkinson’s, the researchers wrote.

“These results demonstrate that motor images generated by people with PD differ according to the side of the body involved in the movement, suggesting underlying differences in the action representations that are used to generate the images,” they added.

Given that difficulties with motor imagery could contribute to or worsen the physical impairments in Parkinson’s patients, rehabilitation and compensatory approaches targeting these issues, “with a greater reliance on visual information and cognitive processes,” may help ease Parkinson’s motor symptoms, the team wrote.

These approaches may involve the patient listening to a song whose beat matches the pace they want to achieve while walking or recording themselves walking and watching that video.

“It’s a matter of providing additional support before they do the movement to help keep them on track,” Lambert said.