LRRK2 Gene Variant in Parkinson’s Tied to Novel Cell Death Mechanism

In new research, mutation linked to excessive inflammation, tissue damage

Written by |

A specific mutation in the LRRK2 gene — whose variants are often associated with Parkinson’s disease – renders immune cells called macrophages more susceptible to death after infection, according to new research that the scientists say gets back to basics.

The team say this genetic variant, known as the G2019S mutation, alters the shape and function of mitochondria, which are the powerhouses of cells.

Most importantly, the mutation triggers a new cell death mechanism that is linked with excessive inflammation and tissue damage. The data suggest that a similar mechanism may be involved in cells of the central nervous system (CNS), comprised of the brain and spinal cord.

Such findings have clear implications for the management of Parkinson’s, according to researchers.

“As mutations in LRRK2 are notoriously associated with both inherited and sporadic PD [Parkinson’s disease], it will be important to translate our findings to cells in the CNS,” the team wrote.

Investigating LRRK2 gene mutations

The study, “Mitochondrial ROS promotes susceptibility to infection via gasdermin D-mediated necroptosis,” was published in the journal Cell.

While the causes of Parkinson’s remain incompletely understood, genetics are known to play a role in determining disease susceptibility. Numerous mutations in the mitochondrial-associated LRRK2 gene have been tied not only to altered Parkinson’s risk, but to other disparate inflammatory human diseases. These include cancer and IBD, or inflammatory bowel disease.

“Mutations in the protein LRRK2 have been associated with multiple important human diseases that, at face value, have very little to do with each other — Parkinson’s disease, leprosy, inflammatory bowel and Crohn’s disease, and cancer,” Kristin L. Patrick, PhD, the study’s co-lead researcher and an assistant professor at Texas A&M University School of Medicine, said in a press release. Patrick is working with co-lead Robert O. Watson, PhD, an associate professor at the same institution.

While mitochondria are traditionally known as the cell’s powerhouses, an increasing body of research show they play key roles in immune defenses and how cells die. However, how perturbations to mitochondria may drive inflammation and lead to awry immune responses remains little understood.

Learning how mutations in mitochondrial-associated genes may impact immune system responses could offer a glimpse to the intricacies underlying many diseases, including Parkinson’s, and open potential new avenues for treatments, according to the scientists.

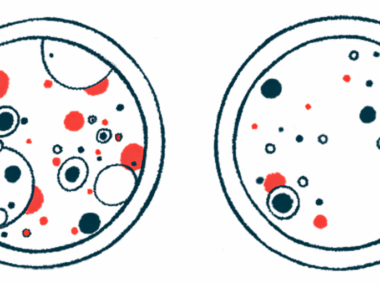

In this new study, the team focused on the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 gene. Using mice macrophages, a type of immune cell that can detect and kill bacteria and other harmful organisms, the researchers first observed that the mutated LRRK2 protein caused the mitochondria to look fragmented when compared when macrophages from healthy (wild-type, WT) mice. The WT mice served as controls.

Also, the same fragmented mitochondria were seen when the mutation was introduced in fat cells of Drosophila melanogaster — commonly known as fruit fly — an often-used animal model of disease.

To understand how the macrophages would respond to an infection, the researchers infected both WT and mutated macrophages with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is the bacterium that causes tuberculosis.

Researchers observed that mutated macrophages were more prone to die after infection when compared with controls, but also that the infection triggered a switch in the cells’ death mechanism. Specifically, they found that the altered mitochondria in the mutated LRRK2 macrophages triggered a new type of cell death, called necroptosis.

When cells die from necroptosis, they release chemical signals that trigger an aggressive inflammatory immune response. Mice carrying the mutated LRRK2 gene, when exposed to M. tuberculosis bacteria, had excessive inflammation in the infected tissues, which was linked with worse outcomes.

While the study focused primarily on macrophages and tuberculosis infection, the novel unveiled mechanism of how the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 gene impacts cellular fate may have wider implications.

“Our work demonstrates that a common mutation in LRRK2 triggers a new type of cell death that elicits hyperinflammation in response to infection,” Patrick said. “Cell death and inflammation could be the thing that connects LRRK2 to all these disparate human diseases.”

The findings support the potential of using LRRK2 inhibitors — already being developed by pharmaceutical companies — to treat diseases like Parkinson’s.

“Our research has positioned us to take these drugs and study them in the context of the immune response,” said Patrick. “We are about to embark on studies to see whether drugging LRRK2, as well as other proteins involved in this new cell death pathway, could improve tuberculosis infection outcomes.”

The research, developed in academia, is yet another example of how studying basic mechanisms of disease may translate into new treatment options for patients with Parkinson’s and other disorders.

“It’s exciting to see how basic science research that digs deep into how molecules work can identify unexpected connections between seemingly unrelated diseases and open up new avenues for therapeutic intervention,” Patrick said.