Long-term tai chi may slow Parkinson’s, lower medication need

Greatest reductions in dyskinesia, cognitive impairment, restless leg syndrome

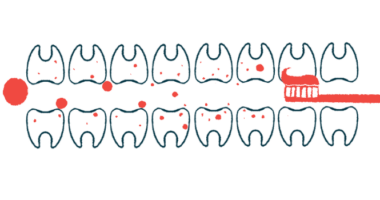

Regularly practicing the Chinese martial art tai chi may slow the progression of motor and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, and delay needing to increase the dosage of medication over time, a study suggests.

The benefits of one-year of tai chi extended to an overall reduction in complications linked to Parkinson’s, with the greatest differences seen for erratic, involuntary movements, called dyskinesia, cognitive impairment, and restless leg syndrome, which is an uncontrolled urge to move the legs.

“Tai chi training was found to have a long-term beneficial effect on [Parkinson’s], with improvement in motor and nonmotor symptoms and a reduction in the prevalence of complications,” wrote a team of researchers at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. “The long-term beneficial effect on [Parkinson’s] could prolong the time during which patients are nondisabled, resulting in a higher quality of life, a lower caregiver burden and less drug usage.”

The study, “Effect of long-term Tai Chi training on Parkinson’s disease: a 3.5-year follow-up cohort study,” was published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Does tai chi have long-term benefits?

Many of the symptoms of Parkinson’s occur as a result of the progressive loss of dopamine-producing nerve cells in a brain region that controls movement and coordination. Dopamine is a major chemical messenger involved in nerve cell communication.

Medication and surgery are used to help people with Parkinson’s manage their symptoms. But getting regular exercise can help to maintain mobility, improve balance and coordination, and ease nonmotor symptoms.

Tai chi involves sequences of very slow, controlled movements that are combined with breathing control.

The researchers had previously shown that a year of regular tai chi improved waking skills and balance in early-stage Parkinson’s patients.

“Previously published research suggests that tai chi eases Parkinson’s symptoms in the short term, but whether this improvement can be sustained over the long term isn’t known,” according to a press release from BMJ, the journal’s publisher.

In the new study (NCT05447975), the researchers examined the long-term benefits of tai chi with Parkinson’s. They compared 143 adults (78 men, 65 women; mean age 66.7) who practiced tai chi twice a week for an hour with 187 patients who served as controls and who didn’t exercise but were matched for age, sex, disease duration, and disability.

All were followed over an average of 4.3 years. Motor and nonmotor experiences of daily living and complications of Parkinson’s were evaluated using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) at the study’s start, or baseline, and in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Improved UPDRS scores, reduced medicine needs

Tai chi practice significantly slowed down the yearly progression of Parkinson’s — the total UPDRS scores increased (got worse) by about 3 points among tai chi participants versus nearly 5 points among controls in each year from 2019 to 2021.

Tai chi practice was also associated with significantly smaller score increases in the UPDRS part III, which assesses motor symptoms, indicating slower progression. Tai chi patients also performed better on the Timed Up and Go test, which measure how fast one can walk, and on the Berg Balance Scale, which assesses balance.

Practicing tai chi also slowed down worsening of cognitive function, autonomic symptoms, sleep, and quality of life. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary bodily functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and gastrointestinal function.

It was significantly less common for tai chi participants to have dyskinesia (1.4% vs. 7.5%), off episodes, which occur when the effect of treatment wears off (1.4% vs. 6.4%), dystonia or spasms (0% vs. 1.6%), hallucinations (0% vs. 2.1%), mild cognitive impairment (2.8% vs. 9.6%), and restless legs syndrome (7% vs. 15.5%).

Dizziness, back pain, falls, and bone fractures caused by falls, however, were about as common among tai chi participants as controls.

The proportion of patients who needed to increase their medication was significantly lower among those who engaged in tai chi both in 2019 (70.6% vs. 83.4%) and 2020 (87.4% vs. 96.3%).

In 2021, while all the patients in both groups needed to increase their medication, the average increase in levodopa equivalent daily dose — the sum of all Parkinson’s medications taken — was significantly lower among tai chi participants (204 vs. 436.8 units per day).

“In our study, delayed progression in motor function … and continuous improvement in quality of life … sleep … and cognition … were found in the tai chi group,” the researchers wrote, adding “the prevalence of complications (dyskinesia, wearing-off phenomenon, dystonia) and several nonmotor symptoms (hallucinations, [mild cognitive impairment] and restless legs syndrome) were lower in the tai chi group.”

The researchers said theirs was the first study they knew of that showed tai chi can “maintain its long-term beneficial effect on [Parkinson’s disease],” but noted it “can’t establish cause and effect,” because it was an observational study. They also acknowledged that the “number of study participants was relatively small and they weren’t randomly assigned to their group.”