Combined DBS approach found safe, feasible in Parkinson’s

Data suggest more DBS-Plus study warranted, researchers say

Written by |

Inserting a piece of nerve tissue from a patient’s ankle into the brain during deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery appears a safe and feasible way to support damaged dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease, with the goal of slowing symptom progression.

That’s according to results from a Phase 1 clinical study (NCT02369003) watching for any side effects of that combined approach, called DBS-Plus, over the course of 15 years. The most common complaint during the first two years was pain or tingling in the foot or ankle, which eased over time and wasn’t bothersome.

“The results from this study encourage us to perform more clinical trials on this procedure in the future,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Two-year feasibility and safety of open-label autologous peripheral nerve tissue implantation during deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease,” was published in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. Craig van Horne, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon and professor of neurosurgery at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, led the research team.

Parkinson’s disease occurs when dopaminergic neurons in a part of the brain called substantia nigra are damaged. Dopaminergic neurons are responsible for producing dopamine, a chemical that signals for motor control, so their loss results in motor symptoms like tremor, slow or stiff movements, and problems with walking.

DBS and Parkinson’s

The team is testing whether taking a piece of a patient’s peripheral nerve tissue, found outside the brain and spinal cord, and inserting it into the substantia nigra while the patient undergoes DBS is a safe and feasible way to support damaged dopaminergic neurons.

Unlike neurons in the brain, peripheral nerves are likely to regenerate and may release chemicals that support the survival and function of dopaminergic neurons. This would be expected to stop or even reverse damage, slowing Parkinson’s progression over time.

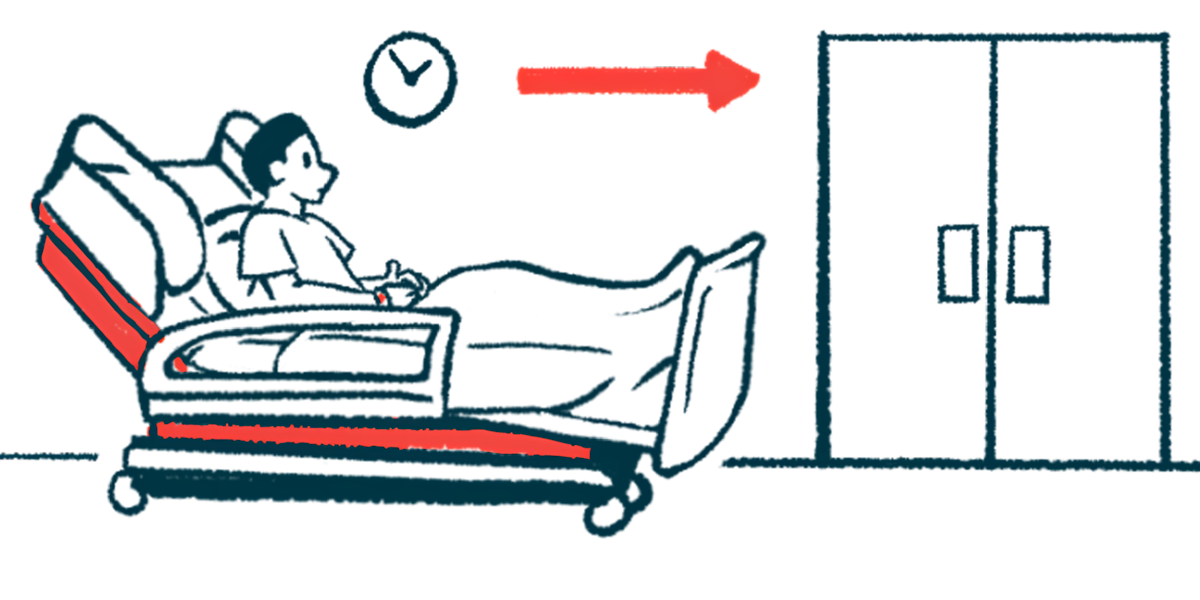

The study involved 13 men and five women with Parkinson’s, with an average age of 62, who were planning to have DBS surgery. The procedure involves placing small wires in the brain to send electrical signals to fine-tune the activity of specific parts of the brain to ease motor symptoms.

All 18 patients underwent DBS surgery in both sides of the brain. Then a small piece of the sural nerve, which runs just below the skin’s surface in the back of the leg down to the ankle, was taken and implanted into one side of the brain, opposite the side with more severe motor symptoms.

The team aimed to check patients’ motor symptoms at five visits over two years. Of the 18 patients, 17 completed all the follow-up visits within that time frame, the exception being a patient who completed the final visit 15 months later due to medical and personal issues unrelated to the study. Of a total of 90 visits, patients attended 83 (92%). Patients “were willing to return for study visits and exams,” the researchers wrote.

MRI scans didn’t reveal any abnormalities potentially related to the implant or the implant procedure. Consistent with the safety profile reported during the study’s first year, the most common side effect was loss of sensation in the foot or ankle (71%), followed by extreme sensitivity (14%) and wound infection (14%) in the ankle.

“No additional study-related adverse events were reported beyond the results presented in our one-year interim report,” the researchers wrote. Likewise, “MRI scans conducted at the two-year mark did not identify any indication of anomalous growth or signs of infection,” suggesting that DBS-Plus is safe, they wrote.

Patients also underwent neurocognitive assessments. Despite changes in working memory and color naming, reductions were small and typical of DBS. All scores remained in the normal range, suggesting DBS-Plus didn’t “add incremental risk of cognitive changes beyond those expected following standard of care DBS.”

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part 3 measures motor symptoms, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms. Beginning at six months, there was a significant, 9.4-point reduction, which remained stable, suggesting no decline in motor function.

Results also showed a reduction in dyskinesia, involuntary movements that occur in Parkinson’s patients.

The study “met its primary endpoints of feasibility and safety,” and the results “encourage additional work and support the concept of future blinded clinical trials,” the researchers wrote.