Molecule from Fat Burning Linked to Protein Clumps That Typify Parkinson’s in Study

A molecule created by the brain burning fat for fuel can accumulate in some people and turn toxic, playing a key role in their possibly developing Parkinson’s disease, researchers at Purdue University report.

These findings, in the study “Acrolein-mediated neuronal cell death and alpha-synuclein aggregation: implications for Parkinson’s Disease” published in Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, could also aid in earlier disease diagnosis and new treatment discoveries.

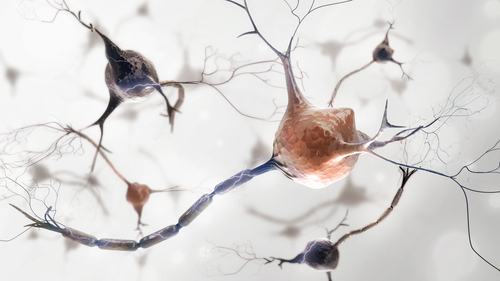

The researchers found that acrolein, a byproduct of burning fat — which brain uses as fuel — that is normally eliminated from the body can promote the accumulation of alpha-synuclein. This buildup, in turn, leads to nerve cell death in the substantia nigra, a brain area crucial for movement control. Damage to nerve cells in this region linked to clumping of the alpha-synuclein protein is a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease.

Using a rat model of Parkinson’s, the team observed that acrolein levels were unusually high in these rats and toxic, leading to alpha-synuclein clumps in their brains.

Importantly, they also found a molecule that in these animals addressed both the toxic protein accumulation and the disease symptoms linked to it.

“Acrolein is a novel therapeutic target, so this is the first time it’s been shown in an animal model that if you lower the acrolein level you can actually slow the progression of the disease,” Riyi Shi, PhD, the study’s senior author, said in a Purdue news article written by Steve Tally. “This is very exciting. We’ve been working on this for more than 10 years.”

Early promise an animal model, however, may or may not lead to discoveries that help patients. “In decades of research, we’ve found many ways to cure Parkinson’s disease in pre-clinical animal studies, and yet we still don’t have a disease therapy that stops the underlying neurodegeneration in human patients,” said Jean-Christophe Rochet, PhD, a study co-author.

Still, “it’s possible that a drug therapy could be developed based on this information,” Rochet added. “We’ve shown that acrolein isn’t just serving as a bystander in Parkinson’s disease. It’s playing a direct role in the death of neurons.”

The investigators found that hydralazine, a molecule that widens blood vessels and lowers blood pressure — and is an approved blood pressure treatment, eased behavioral problems in these rats, as well as in healthy rats injected with the compound.

Hydralazine, which scavenges acrolein, was also able to lessen neuronal death and lower levels of rotenone, another Parkinson’s-related toxin. “Luckily, this is a compound that can bind to the acrolein and remove it from the body,” Shi said. “It’s a drug already approved for use in humans, so we know there is no toxicity issue.”

Hydralazine may not be the best choice for Parkinson’s patients, however, due to its effects on blood pressure. But “we may find there is a therapeutic window, a lower dose, that could work without leading to unwanted side-effects,” Rochet said. “Regardless, this drug serves as a proof of principle for us to find other drugs that work as a scavenger for acrolein.”

In fact, the team has already “identified multiple candidates” that might “lower acrolein with similar or greater effectiveness, but without lowering blood pressure,” Rochet added.

This discovery might also allow earlier disease detection, Shi said, as acrolein levels “can be detected easily, such as using urine or blood,” meaning its levels could serve as a biomarker.

“The goal is that in the near future we can detect this toxin years before the onset of symptoms and initiate therapy to push back the disease … [maybe] indefinitely. That’s our theory and goal,” Shi added.

Rochet previously worked with a research team in Norway that showed that salbutamol, a common asthma medicine, could lower Parkinson’s risk by half, according to a University of Bergen 2017 report.

“Evidence suggests that salbutamol acts by a different mechanism than hydralazine — that is, by reducing alpha-synuclein accumulation — and thus perhaps salbutamol and an acrolein-scavenging drug could be used together to achieve an even greater therapeutic effect,” Rochet hypothesized.