Bacteria in Patients’ Guts Show Changes That May Weigh on Disease

Written by |

People with Parkinson’s disease have substantial changes in the bacteria living in their gut relative to people without this neurodegenerative disorder, an analysis underscores.

“This dysbiosis [microbial imbalance] might result in a pro-inflammatory status which could be linked to the recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms affecting PD [Parkinson’s disease] patients,” its researchers wrote.

These findings were in the study “Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation,” published in npj Parkinson’s Disease.

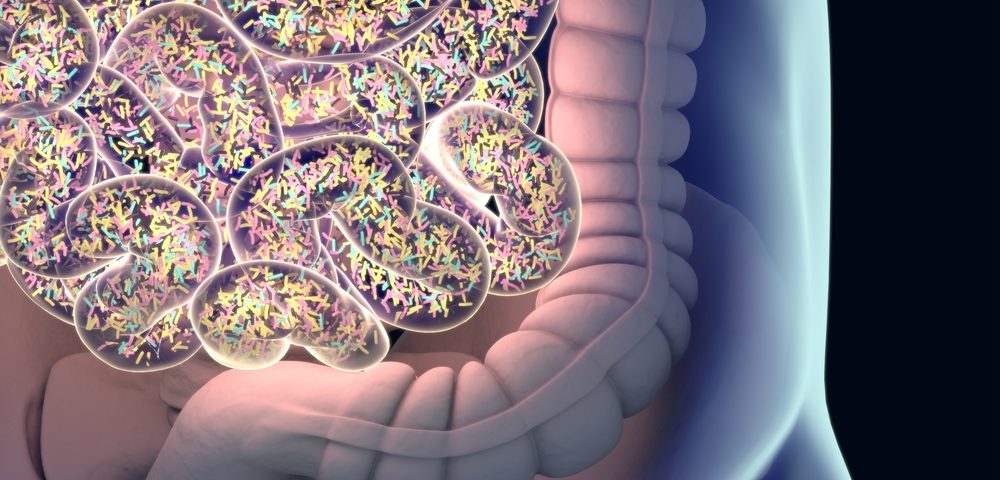

The human gut is home to billions of bacteria, called the gut microbiome. These bacteria have profound effects on, and are affected by, the health of the person in which they live.

Emerging research has indicated that the gut microbiome may be altered in Parkinson’s patients. However, individual studies often find inconsistent — or even contradictory — results, which has made it difficult for researchers to get a holistic understanding of the relationship between Parkinson’s and the gut microbiome.

A team of researchers with the Quadram Institute Bioscience, in the UK, conducted a meta-analysis to better understand this relationship. A meta-analysis is a type of study in which scientists synthesize data from multiple, previously published studies. Because they assess data from multiple works, meta-analyses generally have more statistical power than individual studies.

Researchers analyzed data from 10 previously studies, which reported data on nine groups of people (two studies covered the same group at different points in time). All were case-control studies, meaning they analyzed and compared the gut microbiomes of cases (people with Parkinson’s) compared with controls (people without Parkinson’s). Collectively, the studies included data on 1,269 people with and without Parkinson’s.

All of the studies used 16S rRNA-gene amplicon sequencing to assess the gut microbiome. Simply put, this technique determines what types of bacteria are in a given sample by sequencing a specific part of the bacteria’s genetic code.

A major finding from this meta-analysis was that, even though all these studies used the same overall technique, there were many methodological details that differed study-to-study.

“Various sampling protocols were used across studies, with considerable variation in the methods adopted to preserve the samples before processing,” the researchers wrote. “In some cases, samples were kept at room temperature for up to 48 hours before analysis, in others, samples were stored either in DNA preservative or on ice. DNA extractions and sequencing strategies also varied across studies.”

Statistical analyses on the pooled data found a greater effect on the variance of the gut microbiome than disease status. In other words, study-to-study differences in the gut microbiome were more profound, in a statistical sense, than differences between Parkinson’s cases and control individuals.

Methodological differences, the researchers wrote, “might be the main reasons for the heterogeneity [variability] across the datasets we considered.” They noted a need for further research in this area, and for efforts to better standardize data collecting methodologies.

The researchers then performed additional statistical analyses, which attempted to account for intra-study variability, in order to look for differences in the gut microbiome of people with or without Parkinson’s.

They found a few noteworthy results. For example, people with Parkinson’s generally had more diverse gut microbiomes. Specifically, Parkinson’s patients tended to have lower levels of bacteria that are usually abundant in the guts of healthy people, and higher levels of bacteria that are typically rare in the healthy gut.

Parkinson’s patients also tended to have lower levels of bacteria that produce butyrate, a compound important for the activity of the cells that line the gut and for mediating cross-talk between the gut and the nervous system, the team reported. Increased levels of bacteria that produce methane were also evident, which the researchers speculated could, together with bacteria that deplete mucus, be tied to constipation in Parkinson’s patients.

Such alteration in the diversity and abundance of different types of bacteria “points towards an important role of the gut microbiota in modulating the immune function in this disease,” the researchers wrote.

While the “variability across studies is very big… we can still detect differences between the gut microbiome of patients and controls. This means that microbiome alterations in Parkinson’s disease are consistent across sampling cohorts [groups],” Stefano Romano, PhD, a researcher at Quadram and study co-author, said in a press release.

“The restoration of a balanced microbiome in patients might alleviate some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s, and this is a really exciting route of research we are exploring,” Romano added.

A noteworthy limitation of this study is that the analyses were not designed to find cause-and-effect relationships. That is, it is not clear whether Parkinson’s causes alterations to the gut microbiome, or whether changes in the gut microbiome predispose a person to Parkinson’s and affect its course.

Additionally, most patients in these studies were actively receiving treatment, making it difficult to tease out whether effects seen are due to Parkinson’s itself or to its medications.