Low White Blood Cell Counts May Indicate Early Stages of Parkinson’s

People with low levels of lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, may be at higher risk of Parkinson’s disease later in life, a large database study reports.

While noting that low white blood cell counts may be a consequence of early Parkinson’s or of a yet unknown cause — these blood cells being part of the immune system — the scientists said their measures still can help to identify people at very early stages of the disease.

“Lower lymphocyte [white blood cell] count, although lacking specificity as a biomarker in isolation, may enhance efforts to identify patients who are at the earliest (i.e. pre-clinical) stages of PD [Parkinson’s disease],” the researchers wrote.

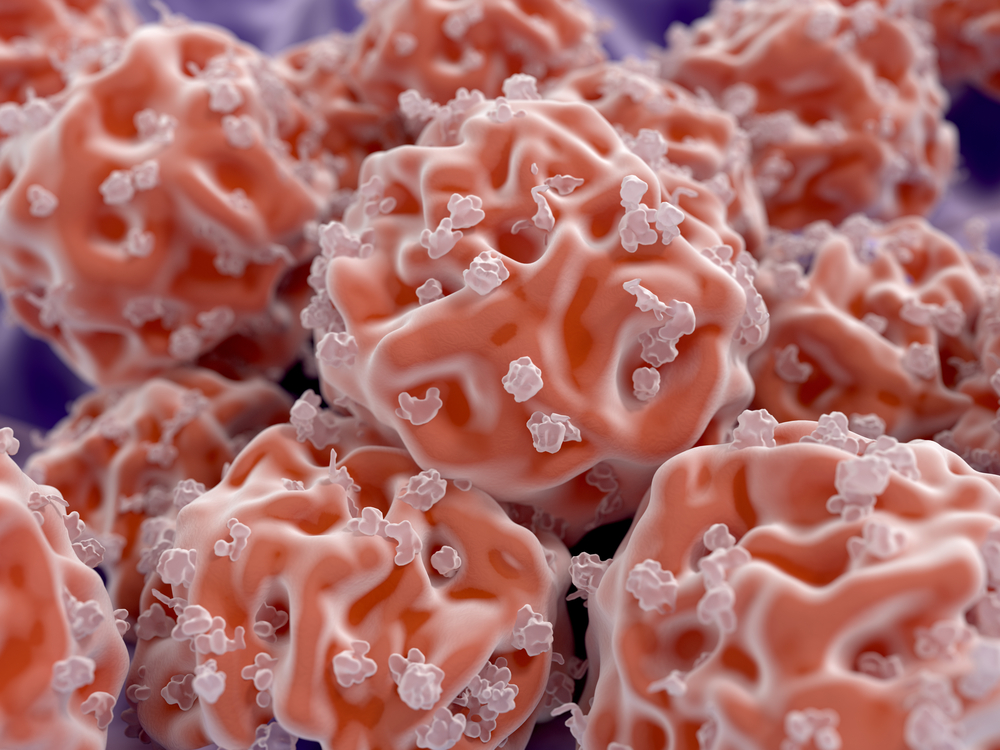

Lymphocytes include such immune system cells as natural killer cells, T-cells, and B-cells.

These findings were reported in the study, “Lower lymphocyte count is associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease,” published in the journal Annals of Neurology.

Parkinson’s, a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons, affects around 2% of adults ages 65 and older.

It typically is only identified after motor problems are evident, but at that point about 50% of a person’s dopamine-producing neurons are already lost, the scientists wrote. For this reason, “there is an urgent unmet clinical need for earlier identification of PD [Parkinson’s disease] and development of therapies which could slow, prevent, or reverse the progression of the disease.”

Previous studies have shown that Parkinson’s patients tend to have lower white blood cell counts than their healthy peers, suggesting that immune system dysregulation may play a role in disease development and certain blood measures may be useful in predicting its onset.

To explore a possible link between white blood cell counts and Parkinson’s, researchers analyzed long-term clinical records of more than 500,000 people, ages 40–69, who were part of the U.K. Biobank, a large biomedical database. Their goal was to determine if “immune dysregulation is detectable in the years prior to PD diagnosis.”

A total of 2,134 Parkinson’s patients were among these people. After excluding both those with comorbidities (like asthma or diabetes) that could influence immune cell levels and patients diagnosed prior to entering the U.K. Biobank, investigators identified 465 Parkinson’s patients to be included in their analyses.

These people were matched by sex and approximate age to 312,125 people without Parkinson’s, serving as controls. Statistical analyses were used to assess the relationship between blood measures made at entrance into the U.K. Biobank (baseline measures) and the development of Parkinson’s.

Low lymphocyte counts were found to associate with an increased risk of Parkinson’s, with risk rising by 18% each time lymphocyte counts dropped by one standard deviation, analyses showed. (Standard deviation is a statistical measure of the amount of variation or dispersion from the mean for a given parameter, in this case, white blood cell counts. One standard deviation normally includes about one-third of all possible values for that parameter.)

Analyses also indicated that low levels of monocytes and eosinophils — two other types of white blood cells — along with low levels of C-reactive protein, an inflammation marker, were all associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s later in life.

Of these various blood parameters, however, only lower lymphocyte counts were linked to a greater risk of Parkinson’s in subsequent analyses.

“In conclusion we report that lower lymphocyte count is associated with higher risk of subsequent diagnosis of PD in a large UK cohort,” the researchers wrote.

Evidence also suggested the relationship between low white blood cell counts and Parkinson’s may be causal, meaning one (low counts) leads to the other (the disease). More studies, however, will be needed to clarify this, the researchers wrote.

“PD is known to have a long latency between biological onset and clinical presentation. As such a proportion of the incident PD cases included may have been clinically incident but biologically prevalent at the time of [patient] recruitment,” the researchers wrote. “We cannot be certain that lymphopenia precedes biological disease onset and it could therefore be a marker of pre-clinical PD.”

Still, “there is evidence to support a mechanistic link between lower lymphocyte count and PD,” they continued. “Further work is required to replicate these findings in other cohorts, and to address the mechanisms underpinning this relationship.”