Spectrum Stage Theory Seeks a Better Understanding of Parkinson’s

Written by |

When I was struggling with healthcare providers to arrive at the right diagnosis, I kept wondering, why is Parkinson’s so difficult to diagnose?

I asked my favorite neurologist, Dr. Donald Higgins Jr., “Has anyone come up with a good theory explaining the large variability in how Parkinson’s presents?” He answered that there was none. This column is dedicated to him.

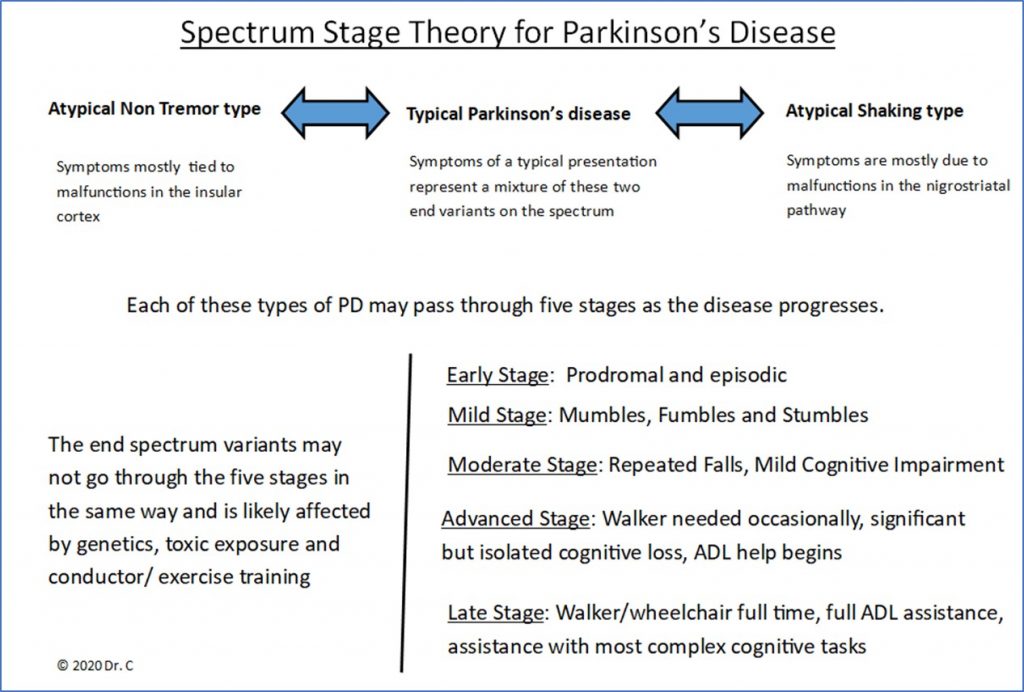

Other Parkinson’s patients have told me, “If you have seen one PD patient, then that’s what you’ve seen.” The following figure represents an early version of a new theory to help explain the wide range of clinical features associated with Parkinson’s disease:

The evidence to support the features in this new theory has been presented in earlier columns. Let’s review:

1. Growing evidence suggests that this disorder may actually be two diseases; one is more brain-centered, while the other is body-centered. Reader comments to my columns suggest many people have nontremor Parkinson’s. Readers report a striking similarity of shared symptoms that do not necessarily include tremors.

2. A second major area in the brain, called the insular cortex, is linked to dopamine use. This second dopamine center is thought to be tied to many of Parkinson’s nonmotor symptoms. I present as a case study for atypical nontremor Parkinson’s, at the opposite end of the spectrum from the more obvious shaking PD.

3. The new theory needs a new definition of early-stage PD. Research on prodromal features has been accumulating, pointing us toward a better understanding of early PD. Many readers of my columns report symptoms 10 to 20 years before final diagnosis of Parkinson’s.

4. Early intervention with conductor training and physical exercise may have strong influence on the presentation, management, and progression of Parkinson’s. Not only do mixtures of the two variants in the spectrum contribute to a diverse presentation, but also to premorbid and comorbid statuses. Readers report success with physical and mental exercise. If you don’t use it, you lose it.

There is no reason to assume that the disease process attacking dopamine neurons would be uniform across the population. Viewing Parkinson’s as a spectrum between two extreme variants of the disease (influenced by brain, body, and lifestyle) helps to explain the varied clinical presentations, including the reason that about half of those diagnosed with PD acquire depression or anxiety only after diagnosis.

Simply put, how you use your brain affects how it functions, especially following trauma or brain disease. The brain is malleable and responds to what we do most with it. It develops easy-to-use neural pathways along well-worn paths of feeling, thought, and action. Some PD variability is likely due to these paths being disrupted by the disease and then modified as we try to cope (sometimes ineffectually). With this new theory, we can develop brain retraining programs that could mitigate some effects of Parkinson’s.

It all starts with a theory that better describes the way the disease presents. In commentary on an article by Melissa J. Armstrong and Michael S. Okun in the journal JAMA Neurology, titled “Time for a New Image of Parkinson Disease,” David Blacker, a physician at the Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, offers a refreshingly honest perception: “What we say as doctors to patients is highly impactful; words need to be chosen carefully and perceptions of illness count. I suspect that mental perception of PD may even influence progression; if a negative, nihilistic image is formed around the time of diagnosis, the self-fulfilling prophecy concept, combined with apathy, could contribute to lack of engagement in physical therapy and mobility, which I suspect accelerates progression.”

Blacker reveals his journey in a most insightful manner in his article, “A Neurologist with Parkinson’s Disease,” published in the journal Practical Neurology. He notes that, “I now feel much more confident with the early diagnosis and management and have a much greater insight into the condition.”

Another comment by Jonny Acheson, a physician at University Hospitals of Leicester in the U.K., agrees that what is needed is a “modern image that a person with Parkinson’s can look at and relate to, something that says: yes this is me.”

The Spectrum Stage Theory offers a more complete picture of the disease. However, it is a fledgling construct and should probably be called a “rudimentary theory.” It is the coat hanger waiting for the coat. This theory sketch is presented for peer review, for discussion, and most of all, for improvement in our perceptions.

And we are pleased to announce that my book “Possibilities with Parkinson’s and the Spectrum Theory” has been accepted for publication!

***

Note: Parkinson’s News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Parkinson’s News Today or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to Parkinson’s disease.

Rob W

Dr. C I recently read your article on spectrum stage theory and I found it quite interesting. I was 33 when diagnosed, (now I am 47) have no tremor, and have a really hard time focusing on one task and I cry like a baby at the dumbest things! It's really quite embarrassing. My symptoms substantially improve most of the time with exercise such that I can sometimes skip a dose of Sinemet or else I get severe dyskinesia. I'm assuming per this model I would fit more on the left side of the chart. Do you have any recommendations for further reading or research?