Late-stage Patients Show Benefit with Deep Brain Stimulation, Small Study Finds

Written by |

Most people with late-stage Parkinson’s disease showed benefit from continued treatment with subthalamic deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) in a small study in Italy.

The researchers also provided an algorithm intended to help guide treatment decisions for those with late-stage disease.

Their study, “Should We Consider Deep Brain Stimulation Discontinuation in Late‐Stage Parkinson’s Disease?” was published in the journal Movement Disorders.

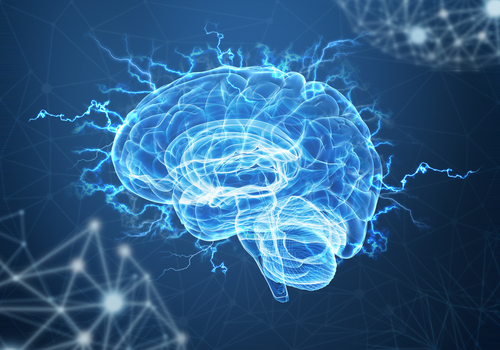

STN-DBS consists of surgically implanting an electrode in the brain to stimulate the subthalamic nucleus — an area involved in motor function — with electric pulses. These charge-balanced, voltage-controlled pulses are generated by a neurostimulator placed under the skin and connected through subcutaneous wires.

STN-DBS is effective in managing Parkinson’s motor symptoms, especially in people with advanced disease whose motor problems no longer improve with medication.

However, its benefits in late-stage Parkinson’s remain unclear, and there are no clear guidelines to help physicians decide when and how STN-DBS discontinuation should be considered in this patient population, often not included in clinical trials.

Sustained use of STN-DBS can require a hospital admission and surgical interventions to replace the neurostimulator (usually every four to five years for non-rechargeable devices).

“For these reasons, the decision to submit a frail and often elderly PD [Parkinson’s disease] patient to this procedure should be supported by a supposed benefit in terms of efficacy on symptoms and [quality of life],” the researchers wrote.

Researchers in Italy set out to evaluate the real “usefulness” of subthalamic deep brain stimulation in people with late-stage Parkinson’s by assessing the percentage of “poor responders.” This was used to develop a treatment decision algorithm to guide physicians about “whether and when DBS discontinuation may be considered.”

The study included 36 late-stage Parkinson’s patients (20 men and 16 women) treated with STN-DBS for at least five years, and whose stimulation parameters and antiparkinsonian medication were stable for at least three months before enrollment.

Patients, recruited at eight Italian DBS-experienced centers, had a mean age of 71.1, mean disease duration of 27.2 years, and had been treated with deep brain stimulation for a mean of 14.1 years.

Their response to STN-DBS was evaluated through changes in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)-part III (which measures motor function) between two conditions: stimulation turned “on,” and stimulation turned “off” (stimulation challenge test).

Each stimulation condition was maintained for at least one hour before assessment, and the sequence of conditions was random, with both patients and physicians being blinded to it. In both conditions, patients had taken their last medication at least 12 hours before the test (off-medication).

Participants were considered “poor responders” if improvements in motor function between the “off” and “on” conditions were less than 10%, as changes of 11% were previously considered as “minimally meaningful.”

Those showing motor improvements of at least 10% were kept on STN-DBS and ended the study, while “poor responders” had their stimulation turned “off” for one month and continued with their medication, after which their motor function was re-assessed.

If a patient’s motor function did not worsen after a month and no adverse events were reported, stimulation was kept “off” after a discussion among the treating physician, patient, and caregiver. But if a person’s symptoms worsened, stimulation was turned “on” again.

Results from the 35 treated patients (one left the study) showed a mean motor improvement of 17% when stimulation was turned “on,” which was statistically significant and considered clinically meaningful.

Significant improvements were mainly observed in patients’ rigidity, slowness of movement, resting tremor, and postural stability. No significant changes were found in speech, rising from chair, freezing of gait, posture, and gait.

Seven patients (20%) were classified as “poor responders.” Symptom worsening occurred in four of them (57%) in the first two weeks without stimulation, and one patient needed to switch “on” the stimulation after three days.

Six patients completed the second assessment, with four showing an increase in their daily dose of levodopa and three requiring the stimulation to be switched “on” again due to symptom worsening.

“Stimulation effect, when present, is usually perceived well during an acute stimulation challenge test, but its entire effect may take days to fully disappear after discontinuation,” the researchers wrote.

Only three of these 35 patients remained with STN-DBS switched “off” after the study ended, “suggesting that the vast majority (92%) of LSPD [late-stage Parkinson’s disease] patients still benefitted from continuous STN-DBS,” they added.

Researchers found no particular patient feature that could predict a “poor response” to this treatment.

“Considering that our protocol was safe and reasonably simple, we propose to translate it into a practical decisional algorithm applicable in DBS-specialized centers, strictly for LSPD patients,” they wrote.

The team also noted that future, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings and improve the management of late-stage Parkinson’s disease under long-term DBS.