Urine Levels of Compound Rise Quickly After Brain Injuries Linked to Parkinson’s, Study Finds

Written by |

Explosions that cause even mild traumatic brain injury can trigger molecular changes that, later in life, lead to neuroinflammation and degeneration, and a greater risk of Parkinson’s disease.

But work by researchers at Purdue University also found that analyzing urine levels of a compound called acrolein may help within days of such injury to identify people — like military veterans — at risk of developing Parkinson’s or other neurodegenerative disorders.

The study, “Acrolein-mediated alpha-synuclein pathology involvement in the early postinjury pathogenesis of mild blast-induced Parkinsonian neurodegeneration,” was published in Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience.

Parkinson’s is characterized by the build-up of damaging alpha-synuclein clumps inside nerve cells. These aggregates, also known as Lewy bodies, can become toxic to cells, triggering neuroniflammation and eventually killing nerve cells.

Blast-induced brain injury is a leading cause of injuries in veterans, as are traumatic brain injuries to athletes like football players and boxers. They associate with a greater susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease compared to the general population. However, information is limited on the underlying mechanisms linking such injury to the disease.

Earlier studies demonstrated that hours and days after even a mild blast-induced brain injury, microvascular and nerve cell damage and neuroinflammation are evident, as are increased levels of harmful oxidative stress.

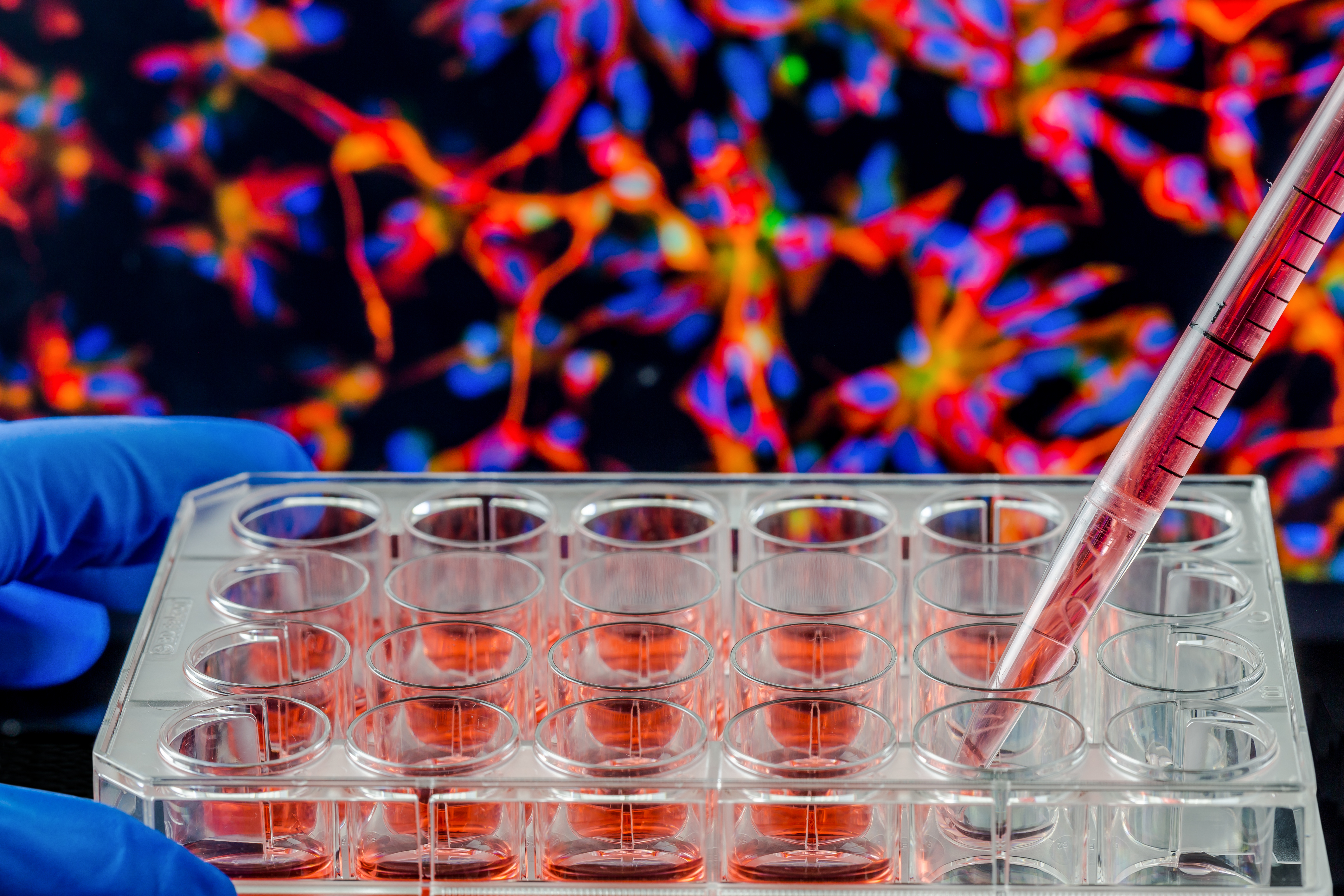

To better understand these processes, the Purdue researchers evaluated rats exposed to mild, blast-induced traumatic brain injury. They focused on analyzing changes in the alpha-synuclein protein and in acrolein, a marker of oxidative stress.

“Most people have heard that traumatic brain injuries are linked to Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, dating back as far as to Muhammad Ali and even earlier. The seriousness of this relationship is readily apparent,” Riyi Shi, PhD, professor at Purdue University’s department of basic medical sciences, said in a university news release by Cynthia Sequin.

“[W]e want to, for the first time, implement a mechanism or protocol capable of connecting brain injuries to these diseases,” Shi added.

The team found that within seven days of their blast-induced brain injury, the animals showed significantly higher levels of acrolein in the urine and the brain, specifically in the substantia nigra and striatum — two brain areas crucial for motor control and both greatly affected by Parkinson’s disease.

“Even at one day post injury, a simple urine analysis can reveal elevations in the neurotoxin acrolein. The presence of this ‘biomarker’ alerts us to the injury, creating an opportunity for intervention,” Shi said.

In addition to higher acrolein levels, increases in the levels of alpha-synuclein variants that are prone to form aggregates were also evident.

Further experiments revealed that acrolein and alpha-synuclein are co-localized in the same brain areas, and can interact in brain injury. In particular, acrolein was found to directly contribute to the clumping of alpha-synuclein and Lewy body formation.

“Taken together, our data suggests acrolein likely plays an important role in inducing [Parkinson’s disease] following [blast-induced traumatic brain injury] by encouraging alpha-synuclein aggregation,” the researchers wrote.

“This study establishes a solid link between the two and opens the door for faster treatments utilizing acrolein urine tests during the days following a traumatic episode,” Shi said. “This early detection and subsequent treatment window could offer tremendous benefits for long-term patient neurological health.”