Appendix Removal Early in Life Reduces Risk of Developing Parkinson’s, Study Shows

Written by |

The healthy human appendix contains Parkinson’s disease-related alpha-synuclein aggregates, and removing the organ early in a person’s life reduces the risk of developing the disease, a study has found.

The study, “The vermiform appendix impacts the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease,” was published in Science Translational Medicine. The work was led by researchers at the Center for Neurodegenerative Science at the Van Andel Research Institute in Michigan.

“Our results point to the appendix as a site of origin for Parkinson’s and provide a path forward for devising new treatment strategies that leverage the gastrointestinal tract’s role in the development of the disease,” Viviane Labrie, PhD, an assistant professor at Van Andel and senior author of the study, said in a press release.

In the brains of Parkinson’s patients, there is a buildup of a protein called alpha-synuclein that forms clumps known as Lewy bodies. These clumps are toxic and lead to neuronal death.

“Gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction is a common nonmotor symptom of PD [Parkinson’s disease], often preceding the onset of motor symptoms by as many as 20 years,” the researchers wrote.

In addition, it has been shown that neurons innervating the intestines of Parkinson’s patients contain aggregated alpha-synuclein.

“Accumulation of alpha-synuclein in the GI tract not only may contribute to the nonmotor symptoms of PD but also has been hypothesized to contribute to PD pathology in the brain,” the researchers said.

Studies have revealed the existence of many alpha-synuclein aggregates in the appendixes of early-stage and established Parkinson’s patients, as well as in neurologically intact subjects.

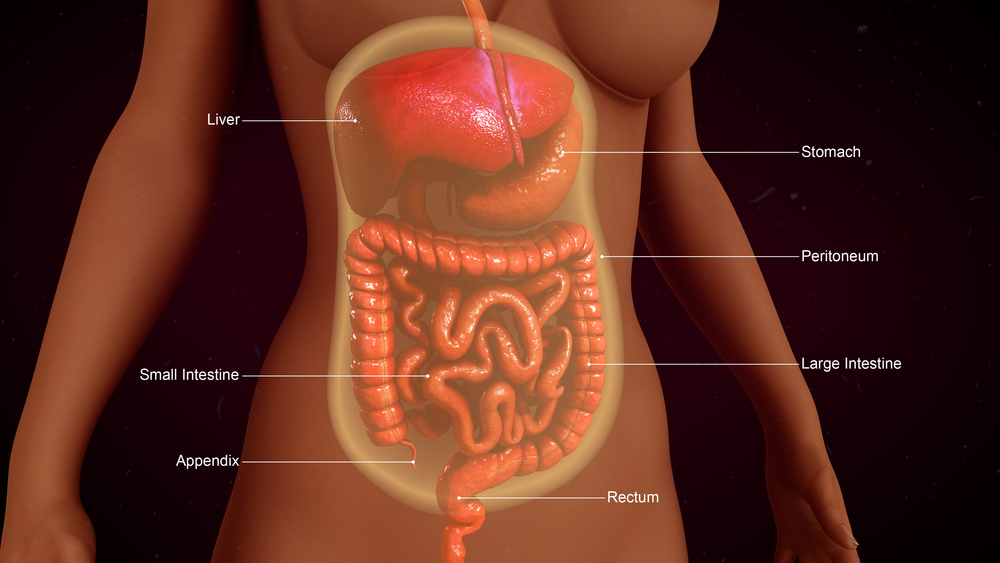

The appendix — a worm-like organ that sticks out of the large bowel in the lower right side of the abdomen — helps the immune system detect and eliminate harmful microorganisms, while regulating the gut’s bacterial composition.

In this study, researchers investigated whether this tiny organ contributes to Parkinson’s disease risk.

They analyzed two separate, yet complementary, epidemiological data sets: the nationwide Swedish National Patient Registry (SNPR) and the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI).

The SNPR contains information on 1.6 million individuals with a follow-up period of up to 52 years. Investigators identified all individuals who had had an appendectomy (surgical removal of the appendix) from 1964 to 2015 and obtained data on their surgical procedure, year of birth, year of surgical procedure, sex, geographic location (municipality), and, when applicable, date and cause of death. For each patient who underwent an appendectomy, there were two control participants who had not had their appendix removed matched in year of birth, sex, and geographic area.

This data-set analysis revealed that appendix removal was associated with a 19.3% lower risk of developing Parkinson’s than controls. Parkinson’s was diagnosed in 1.17 out of every 1,000 patients who had an appendectomy compared with 1.4 per 1,000 in the general population.

The surgery had the greatest impact on those living in rural areas, with a significant 25.4% reduction in Parkinson’s risk, indicating that removal of the appendix might influence environmental risk factors for the disease. Interestingly, no appendectomy-related benefit was observed in the urban area sample.

“The age of PD diagnosis was, on average, 1.6 years later in individuals who had an appendectomy occurring 20 or more years prior than in cases without an appendectomy. We also observed a significant delay in age of PD onset in individuals with an appendectomy 30 or more years prior, but a limited size in this longer latency group precluded further analysis,” the scientists said.

Researchers then looked at the PPMI data set, which contained detailed information about Parkinson’s diagnosis, age of onset, and other demographic factors, as well as the genetic information of 849 patients.

The team chose to focus on individuals who had their appendix removed at least 30 years before being diagnosed with Parkinson’s, because the early-stage phase of Parkinson’s can last for decades before an accurate diagnosis.

Results showed that age at disease onset was significantly delayed by 3.6 years in those who had undergone an appendectomy (54 individuals, representing 6.4% of the Parkinson’s sample), compared with those who had not.

Disease occurrence was not linked to immune disorders not affecting the gastrointestinal tract, nor was it related to the surgical event itself.

Once a Parkinson’s diagnosis had been established, there were no differences in symptom severity between people with and without a history of appendectomy, suggesting the appendix can potentially impact disease mechanism before the clinical onset of symptoms.

The team then explored the interaction between the appendix and environmental/genetic Parkinson’s risk factors. They reported that the surgical procedure delayed the age of onset in subjects with a family history — meaning those with one or two family members with Parkinson’s — but had no effect in individuals without a family history of the disease.

Importantly, those with a mutation in the LRRK2, GBA, or SNCA gene — which are common in hereditary Parkinson’s cases — did not benefit from the appendectomy, indicating that removal of the appendix may be more protective against environmental causes of Parkinson’s rather than genetic ones.

Tissue analysis showed that the mucosa and neurons within the healthy human appendix were filled with aggregated alpha-synuclein. Such accumulation was evident in all age groups, including subjects younger than 20.

Although appendixes of both people with and without Parkinson’s contained disease-prone forms of alpha-synuclein that tend to aggregate rapidly, the Parkinson’s group’s “diseased” protein content was higher than that of the control group.

“We were surprised that pathogenic forms of alpha-synuclein were so pervasive in the appendixes of people both with and without Parkinson’s. It appears that these aggregates — although toxic when in the brain — are quite normal when in the appendix. This clearly suggests their presence alone cannot be the cause of the disease,” Labrie said.

Next, the scientists will search for which appendix-related factor(s) may contribute to Parkinson’s disease.