2 Markers of Parkinson’s Progression May Help Trials in Newly Diagnosed Patients, Study Says

Written by |

Clinical trials in patients with early stage Parkinson’s may benefit from assessing markers of disease progression — namely, changes in the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) and dopamine transporter imaging, according to five-year results in a major observational study.

The study, “Longitudinal Change of Clinical and Biological Measures in Early Parkinson’s Disease: Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative Cohort,” was published in the journal Movement Disorders.

A lack of reliable and objective measures of Parkinson’s progression is a major stumbling block for researchers trying to develop disease treatments.

The Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) is an ongoing observational study that opened in 2010 and is now running at sites in 11 countries and involves about 1,000 people. It aims to speed the development of Parkinson’s therapies by evaluating the efficacy of several markers of disease progression in a large cohort of newly diagnosed Parkinson’s patients and healthy controls.

In total, 423 Parkinson’s patients were recruited for this study, and 358 remained with it for the five years. All were untreated at the study’s start, but soon began treatment with dopaminergic therapies, such as levopoda or dopamine agonists, or other Parkinson’s medications (non-dopaminergic).

Participants were evaluated every six months for a set of different clinical parameters, including MDS-UPDRS, the most commonly used and preferred scale for measuring Parkinson’s disability. But current data is limited on the long-term rate of change for this scale in newly diagnosed patients.

In the study, MDS-UPDRS scores were assessed at two different stages — during off-time periods, typically more than six hours after the last dose of dopamine therapy, and on-time periods or about one hour after taking this treatment.

Patients using non-dopaminergic therapies were assessed during on-time periods only.

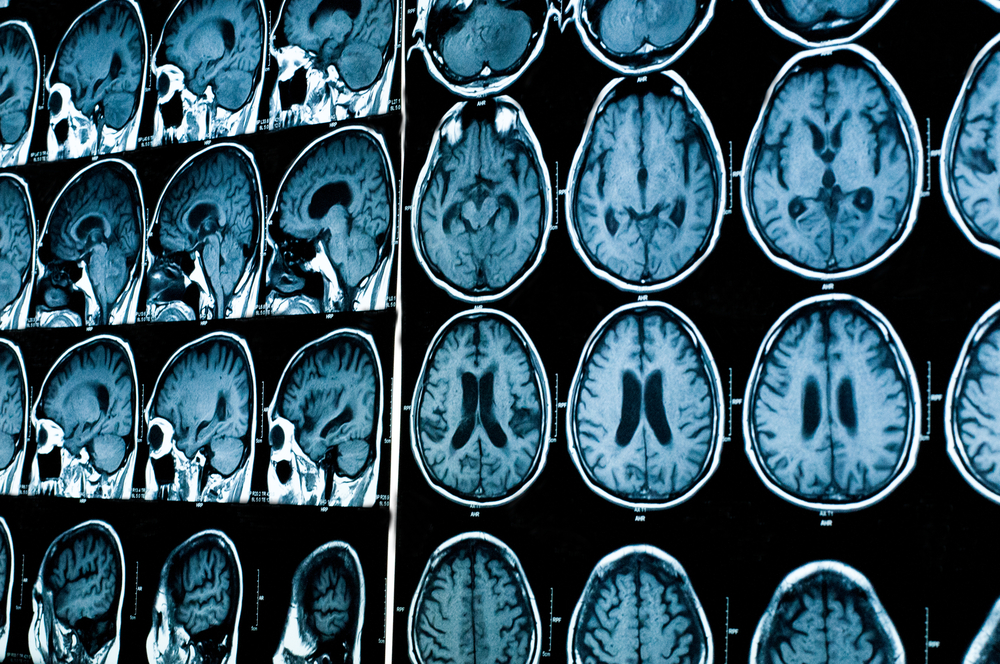

All underwent dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging at baseline (study’s start) and at years one, two, and four of the study. DAT can establish the presence of presynaptic dopamine deficiency, and is increasingly used in clinical trials to exclude people without evidence of such deficiency because they are unlikely to have the pathology that typically causes Parkinson’s.

Data showed significant differences in the rate of change in MDS-UPDRS in those who began dopaminergic therapy compared to those who remained untreated throughout the first year.

“Dopaminergic therapy provides a robust symptomatic benefit in early Parkinson’s, and once dopaminergic therapy is initiated, the rate of change of motor disability flattens until participants reach more advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease dominated by levodopa-resistant symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

A fraction of those treated with non-dopaminergic therapies also showed a change in MDS- UPDRS, but the changes were closer to untreated patients.

“These data reflect the lower potency of these agents,” the researchers said.

People who had no need to begin dopaminergic therapies had milder disease at baseline.

During the study, the researchers saw a marked decrease in dopamine transporter binding, with higher levels evident in the study’s first year compared to years two and four.

Changes in MDS-UPDRS scores and dopamine transporter imaging data did not correlate directly, the team reported, suggesting these two measures are valid on their own as they measure different aspects of Parkinson’s disease that can occur at the same time.

“Our results provide a framework for designing studies that incorporate clinical and DAT imaging measures in de novo Parkinson’s disease participants,” the researchers wrote. “Such studies may signal a more accurate and efficient process toward the development of disease-modifying treatments for Parkinson’s disease.”