Toxoplasma Brain Parasite Modulates Signaling Pathways Common in Parkinson’s Disease

Written by |

Infection with the brain parasite Toxoplasma gondii may increase the likelihood for certain brain disorders, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease, a systematic analysis suggests.

The study, “Toxoplasma Modulates Signature Pathways of Human Epilepsy, Neurodegeneration & Cancer,” was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

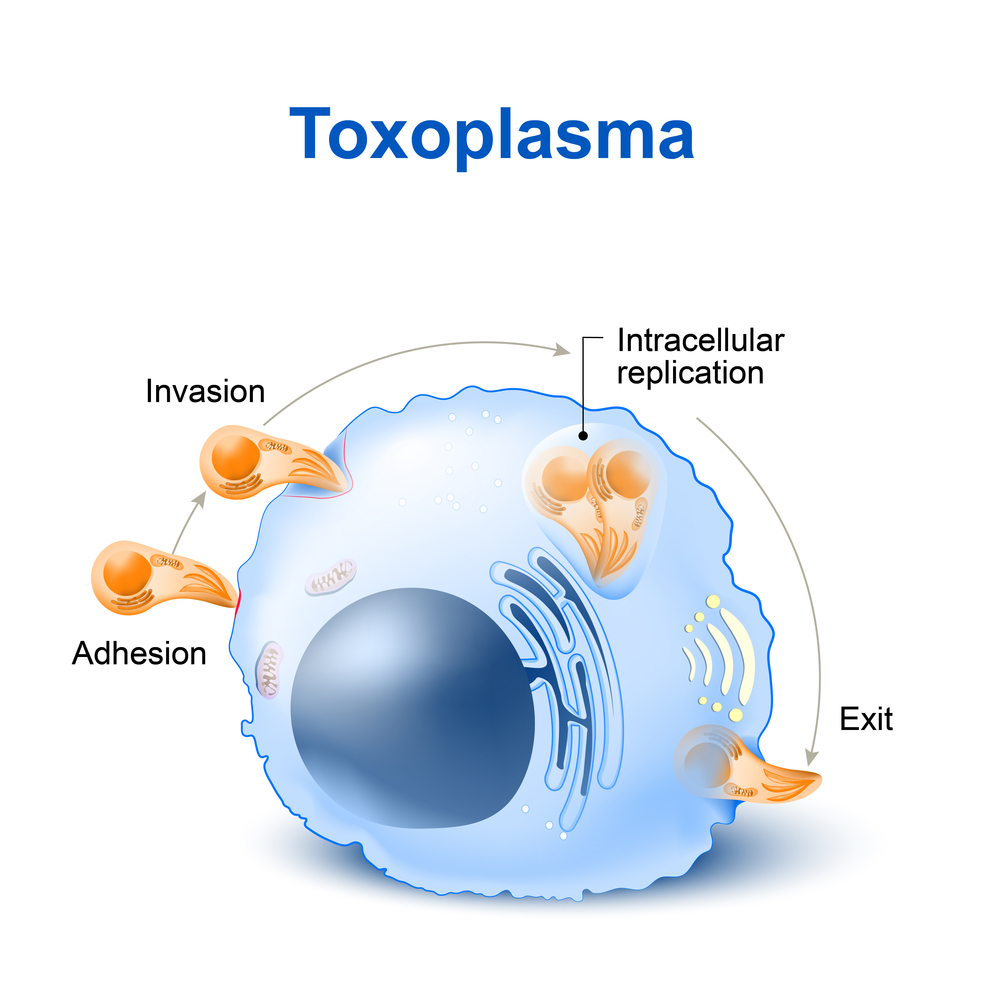

Over two billion people are infected with the brain parasite T. gondii. The infection has been reported as dangerous for pregnant women, as infection in their unborn child might lead to severe damages to the brain, nervous system, and eyes. But recent studies suggest that becoming infected later in life may also carry detrimental consequences.

“We wanted to understand how this parasite, which lives in the brain, might contribute to and shed light on pathogenesis of other brain diseases,” Rima McLeod, MD, medical director of the Toxoplasmosis Center at the University of Chicago and the study’s lead author, said in a press release.

Researchers focused particularly on how the infection may change or even increase the risk for several brain disorders, including epilepsy, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and certain cancers.

“We suspect it involves multiple factors,” McLeod said. “At the core is alignment of characteristics of the parasite itself, the genes it expresses in the infected brain, susceptibility genes that could limit the host’s ability to prevent infection, and genes that control susceptibility to other diseases present in the human host.

“Other factors may include pregnancy, stress, additional infections, and a deficient microbiome. We hypothesized that when there is confluence of these factors, disease may occur.”

Studies with mice and rats showed that acute and chronic infection led to alterations in neurotransmitters, memory, seizures, and neurobehaviors.

And other epidemiologic studies have shown “associations between seropositivity for T. gondii and human neurologic diseases, for example, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases,” the team wrote.

Now, University of Chicago researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of the infected brain to better understand what this parasite does to human brains. They used data from the National Collaborative Chicago-Based Congenital Toxoplasmosis Study, which includes 246 people infected from birth, as well as their families, since 1981.

Teaming up with researchers at J Craig Venter Institute and the Institute of Systems Biology Scientists, they analyzed how gene and protein expression of primary neuronal stem cells from the human brain was perturbed upon Toxoplasma infection.

Using a “reconstruction and deconvolution,” approach, they found that Toxoplasma-affected pathways associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Specifically, they identified certain regulatory small RNAs (microRNAs) and proteins found deregulated in children with severe toxoplasmosis were common in patients with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

Moreover, the parasite manipulates 12 human olfactory receptors, and may likely increase the risk of epilepsy. A wide network of genes altered in many cancers was also modulated by Toxoplasma infection.

“Our results provide insights into mechanisms whereby this parasite could cause these associated diseases under some circumstances,” researchers wrote. “This work provides a systems roadmap to design medicines and vaccines to repair and prevent neuropathological effects of T. gondii on the human brain.”

“This study is a paradigm shifter,” said Dennis Steinler, PhD, director of the Neuroscience and Aging Lab at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University. “We now have to insert infectious disease into the equation of neurodegenerative diseases, epilepsy and neural cancers.”

“At the same time, we have to translate aspects of this study into preventive treatments that include everything from drugs to diet to lifestyle, in order to delay disease onset and progression,” added Steinler, who is also the study’s co-lead author.