Study Sheds Light on Mechanisms of Protein Involved in Genetic Form of Parkinson’s

Canadian researchers have gained new insight into the activation of a protein that plays an important role in the genetic form of Parkinson’s disease.

Findings were published in the study, “Mechanism of parkin activation by phosphorylation,” published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra — the part of the brain responsible for movement.

While most cases occur sporadically, approximately 5-10 percent of Parkinson’s cases are caused by genetic mutations. Specifically, mutations in the genes PARK2, which provides instructions for the making of the parkin protein, and PINK1, which provides instructions for the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 protein, are responsible for an early-onset form of Parkinson’s disease.

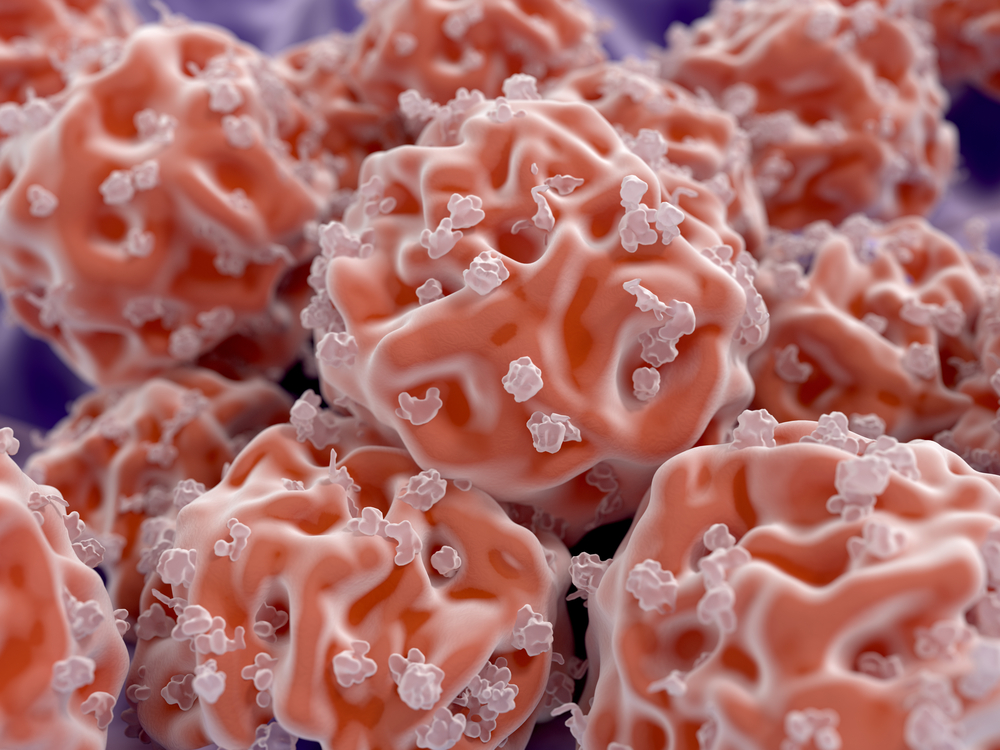

Parkin and PINK1 are part of the mitochondrial quality-control system. Mitochondria play a central role in energy production in cells.

Parkin is a type of enzyme, called an ubiquitin ligase, that carries out a process called ubiquitination. Ubiquitination is like a cellular tagging system: By adding an ubiquitin molecule to a protein, it marks it for degradation. As such, parkin plays a role in clearing away defective mitochondria — a process called mitophagy — by marking them for ubiquitination.

To restrict their ubiquitination function, many ubiquitin ligases are auto-inhibited when their activity is not required. In other words, the structure of parkin is designed in such a manner that its activation sites are not exposed to avoid rampant degradation in the cell.

Activation of parkin requires a change in its structure to bring the site where the ubiquitin molecule binds together with the site responsible for transferring this molecule to the mitochondria — thus marking it for degradation.

McGill University researchers, funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, used powerful X-ray beams and discovered that this process is initiated when PINK1 starts to accumulate on the mitochondrial outer membrane. Then PINK1 chemically adds phosphate compounds — a process called phosphorylation — to nearby ubiquitin molecules. This catches the attention of parkin, which has an affinity for phosphorylated ubiquitin and proceeds to bind the phosphorylated ubiquitin.

Through a mechanism of activation that involves several changes in structure, parkin is able to receive the ubiquitin molecule and eventually transfer it.

“The results provide a complete picture of the activation of parkin,” the researchers wrote.

Understanding parkin’s structure and how it is activated offers hope for targeting this protein as a therapeutic agent to slow or prevent the progression of Parkinson’s disease.