Parkinson’s clinical trial recruiting patients at USC, other locations

Treatment aims to repair patients' motor function, improve quality of life

Written by |

- A Phase 1 trial of a cell therapy is recruiting moderate to severe Parkinson's patients.

- The therapy uses iPSCs to replace lost dopamine-producing neurons.

- The trial monitors safety and motor function for up to five years.

The University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine is recruiting patients for a Phase 1 clinical trial evaluating RNDP-001, an experimental cell replacement therapy being developed by Kenai Therapeutics for moderate to severe Parkinson’s disease.

The company-sponsored REPLACE (NCT07106021), which began dosing late last year, is recruiting up to 12 adults with moderate to severe idiopathic (of unknown cause) Parkinson’s, ages 45 to 75. Two other locations, one at the University of Arizona and another at Ohio State University, are also open for recruitment.

While the trial’s main goal is to test how safe and well tolerated RNDP-001 is, the “ultimate goal is to pioneer a technique that can repair patients’ motor function and offer them a better quality of life,” Brian Lee, MD, PhD, a neurosurgeon at Keck Medicine and principal investigator of the clinical trial, said in a university press release.

Reprogramming stem cells

Parkinson’s is caused by the loss of dopaminergic neurons, the nerve cells that produce dopamine in the brain. Dopamine is a signaling chemical essential for initiating and coordinating voluntary movement. In Parkinson’s, the buildup of abnormal proteins damages dopaminergic neurons, leading to motor and nonmotor symptoms.

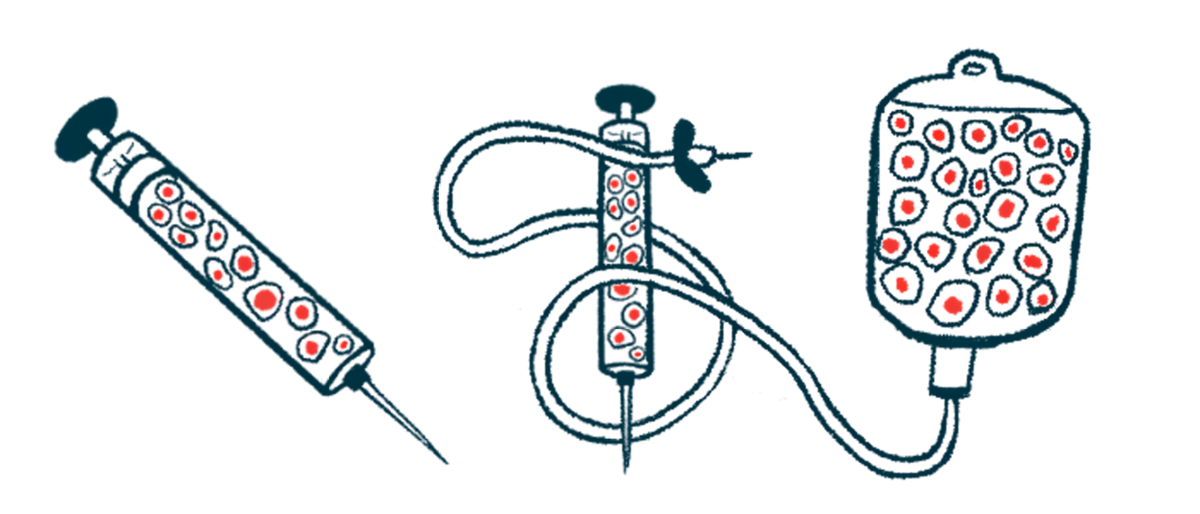

RNDP-001 is derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), adult cells that are reset and reprogrammed so they can become almost any type of cell in the body. These iPSCs can be guided to develop into dopaminergic neurons. The goal is for them to replace the lost nerve cells, repair damaged brain circuits, and ease symptoms.

“We believe that these iPSCs can reliably mature into dopamine-producing brain cells, and offer the best chance of jump-starting the brain’s dopamine production,” said Xenos Mason, MD, a neurologist at Keck Medicine and co-principal investigator of the REPLACE trial.

During the procedure, Lee drills a small hole in the patient’s skull to reach the brain and uses MRI to guide a low or high dose of RNDP-001 into the basal ganglia, the part of the brain that controls movement.

“If the brain can once again produce normal levels of dopamine, Parkinson’s disease may be slowed down and motor function restored,” Lee said.

Patients are closely monitored for 12 to 15 months after the procedure. In addition to testing safety and tolerability, researchers will look for changes in dopaminergic signaling and in on time, periods when symptoms are well controlled with medication. Patients will be followed for up to five years to assess the treatment’s long-term effects.