Heart Drug Found to Slow Plaque Build-up in Blood Vessels in the Brains of Mice

Written by |

Platelets contribute to amyloid-β deposits in blood vessels in the brain by promoting the formation of Aβ aggregates that are central to Parkinson’s disease, but a heart medication — the anti-platelet drug clopidogrel — can help to stop these plaques from forming, researchers at Örebro University in Sweden reported. This last finding, from a study conducted in mice, could constitute a way of alleviating plaque formation and, consequently, dementia, if the mechanism holds for humans.

The research article, “Platelets contribute to amyloid-β aggregation in cerebral vessels through integrin αIIbβ3–induced outside-in signaling and clusterin release,” was published in Science Signaling.

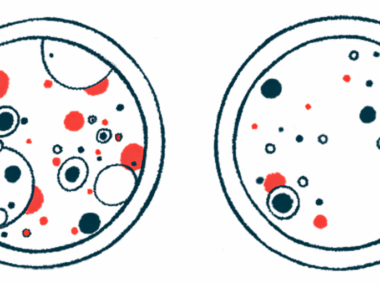

The build-up of pathological amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a vascular dysfunction disorder caused by these plaques, are major contributors to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression and the onset of dementia. Platelets, blood cells with essential functions in blood clotting, are known to accumulate in vascular Aβ deposits, which in turn are the major characteristic of the vascular dysfunction disorder CAA.

Researchers found that platelets directly contribute to CAA by promoting the formation of Aβ aggregates, and that the Aβ aggregates, in turn, activate platelets, creating a pathologic loop that furthers disease.

“Our study is an example of solid biomedical basic research at the cell and molecular levels which points to a link that was previously unknown. What is shown is that cells in the blood may play a significant role in the development of plaque, which is found in patients with Alzheimer’s disease,” Professor Magnus Grenegård said in a news release.

Next, they tested a common heart drug used to prevent blood clots, the anti-platelet agent clopidogrel, in mouse models of AD, and found that this drug reduced Aβ aggregation, slowing down the process of neurodegeneration. The finding showed the drug has the potential to not only reduce the build-up of plaque in blood vessels, but in the brain tissue as well.

“In deep structures of the brain, where certain memory functions are controlled, there was a clear trend of reduced plaque presence,” Professor Grenegård said.

“We do not know if this is transferrable to humans; if the effect would be the same. To find out, new follow-up studies are required. Unfortunately, this is a lengthy process — it will be years before we know. But at least we have identified a new, interesting approach with respect to plaque formation,” he concluded.