Study Examines Proteins’ Roles in Mitochondrial Recycling

Written by |

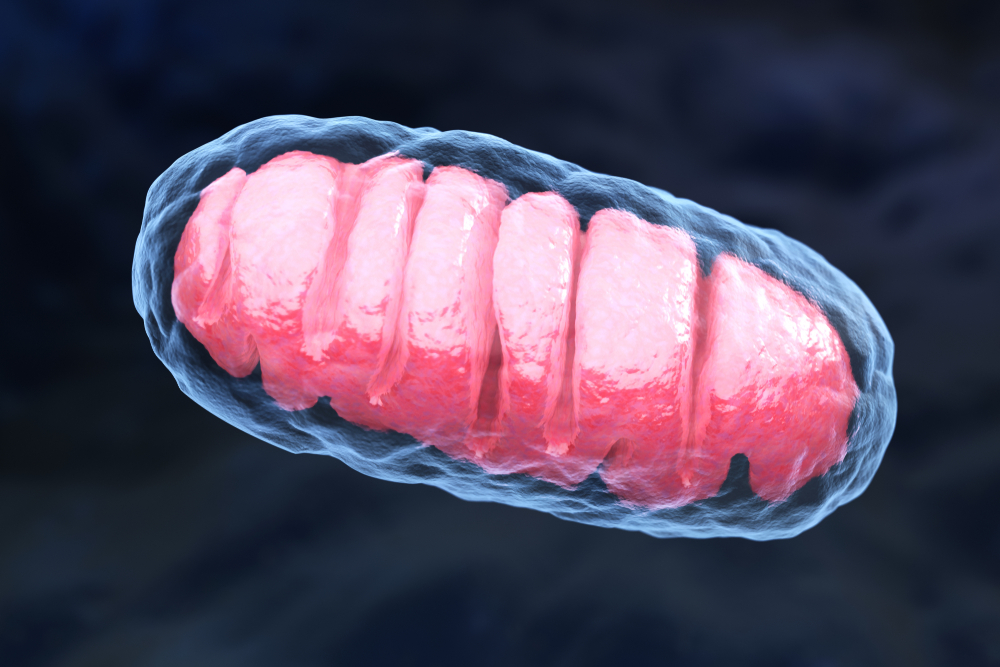

Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock

PINK1 and Parkin — two proteins whose deficiency has been linked to early-onset Parkinson’s — are involved in the degradation and recycling of mitochondria in neurons, a study shows.

While these proteins were known to contribute to mitochondrial recycling in other cell types, this study provides a closer look into mitochondria’s life cycle in neurons, confirming not only PINK1 and Parkin’s role, but also uncovering a new recycling pathway.

“This work gives us unprecedented insight into mitochondria’s life cycle and how they are recycled by key proteins that, when mutated, cause Parkinson’s disease,” Ken Nakamura, MD, PhD, said in a press release. Nakamura is the study’s senior author and an associate investigator at Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco.

“It suggests that mitochondrial recycling is critical to maintaining healthy mitochondria, and disruptions to this process can contribute to neurodegeneration,” added Nakamura, who is also an associate professor of neurology at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF).

The researchers now plan to use the high-resolution approach that allowed them to closely monitor mitochondria’s life cycle in neurons to “investigate how these pathways contribute to disease and how they can be targeted therapeutically,” Nakamura said.

The study, “Longitudinal tracking of neuronal mitochondria delineates PINK1/Parkin-dependent mechanisms of mitochondrial recycling and degradation,” was published in the journal Science Advances.

Mitochondria are the cells’ powerhouses. Mitochondrial deficits are implicated in the development of several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s. The dopamine-producing neurons that are progressively lost in Parkinson’s are sensitive to changes in mitochondrial structure and dynamics, as well as mutations in genes that provide instructions for making proteins involved in such processes.

Notably, mutations in the PINK1 and PRKN genes are associated with early-onset Parkinson’s, or disease onset before age 50. Their resulting proteins, PINK1 and Parkin, have been shown to play key roles in mitochondrial recycling — a process known as mitophagy — in many cell types.

However, whether these proteins have the same role in neurons — which have unusually high energy needs and whose mitochondria appear to be more resistant to Parkin-induced degradation — remains unclear.

Now, by combining time-lapse imaging with powerful microscopy, Nakamura and his team were able to track individual mitochondria inside rodent living neurons over time, and assess how PINK1 and Parkin affected their fate.

“We had to develop a new way of tracking individual mitochondria over long periods of time, almost a full day,” said Zak Doric, the study’s co-first author and a graduate student at Gladstone and UCSF. “Getting that technique up and running was quite a challenge.”

Besides confirming that PINK1 and Parkin also are involved in mitophagy in nerve cells, they were able “to visualize these steps at a level that hasn’t been done before in any cell type,” Nakamura said.

Notably, Parkin was found to be recruited to damaged mitochondria by direct and indirect mechanisms.

In the direct pathway, Parkin is gradually recruited directly into the inside of mitochondria “over many hours, as mitochondria concurrently undergo mild acidification through undefined mechanisms,” the researchers wrote.

In the indirect pathway, Parkin binds to the outer membrane of damaged mitochondria, driving the formation of mitochondria-degrading structures called mitolysosomes, which, to the researchers’ surprise, were dynamic and persisted for hours.

While scientists had assumed that mitolysosomes rapidly broke down mitochondria into molecules that the cell could reuse to build new powerhouses from scratch, Nakamura and his team showed that these mitochondria-degrading structures survived for hours inside cells.

“Until now, nobody has known what happens next to these mitolysosomes,” Nakamura said.

The team found that some of these structures were engulfed by healthy mitochondria, likely representing “a mechanism to enable the recycling of mitochondrial contents, which may be a more efficient process than fully degrading mitochondria before rebuilding them,” the researchers wrote.

Other mitolysosomes were found to spontaneously burst and release their contents, including some functional proteins, into the interior of the cell, “which could enable some contents to be reused by other organelles and others to be degraded further,” by other degrading machinery, the team added.

“This appears to be a new mitochondrial quality control, recycling system,” said Huihui Li, PhD, the study’s co-first author and a Gladstone postdoctoral scholar.

“We think we’ve uncovered a pathway of mitochondrial recycling — which is like salvaging valuable furniture in a house before demolishing it,” Li added.

These findings “define a distinct neuronal mitochondrial life cycle, revealing potential mechanisms of mitochondrial recycling and signaling relevant to neurodegeneration,” the researchers wrote.

“Our study advances our understanding of how these two key Parkinson’s disease proteins degrade and recycle mitochondria.” Nakamura said.

Their high-resolution approach will allow them to conduct future studies aimed at understanding with great precision how Parkin and PINK1 affect mitochondrial recycling in Parkinson’s disease.

More research is needed to assess whether these mechanisms, including the release of mitochondrial contents into the cell, “may initiate immune and other signaling pathways and contribute to the selective vulnerability of neurons to PINK1 and Parkin mutations,” the team concluded.