Dopaminergic Medication Lowers Patients’ Sensitivity to Negative Outcomes in Learning, Study Shows

Written by |

Dopaminergic medication (i.e., levodopa) for Parkinson’s disease appears to bring sensitivity to negative outcomes in learning down to normal levels, a new study shows.

The study, “Dopaminergic medication reduces striatal sensitivity to negative outcomes in Parkinson’s disease,” was published in the journal bioRxiv.

The ability to learn from trial and error plays a major role in decision-making.

Dopamine-producing neurons facilitate learning via trial and error by calculating a value known as the reward prediction error, which refers to the difference between expected and actual reward.

The neurons in the substantia nigra (which are lost in Parkinson’s disease) use bursts and dips of dopamine signaling to relay positive and negative reward prediction error to other parts of the brain, which activates the so-called “Go” and “NoGo” pathways.

When the “Go” pathway is activated, it conveys a signal saying it is OK to proceed with an activity. When the “NoGo” pathway is more active, the action is suppressed.

In Parkinson’s, however, patients lose a substantial portion of dopamine-producing neurons, leading to the depletion of dopamine signaling.

Dopamine medication used by these patients has previously been linked to either behavioral changes during trial-and-error learning or adjustments in approach/avoidance behavior after learning.

But little is known about how dopamine medication leads to differences during learning and how that translates into subsequent changes in approach/avoidance tendencies in patients.

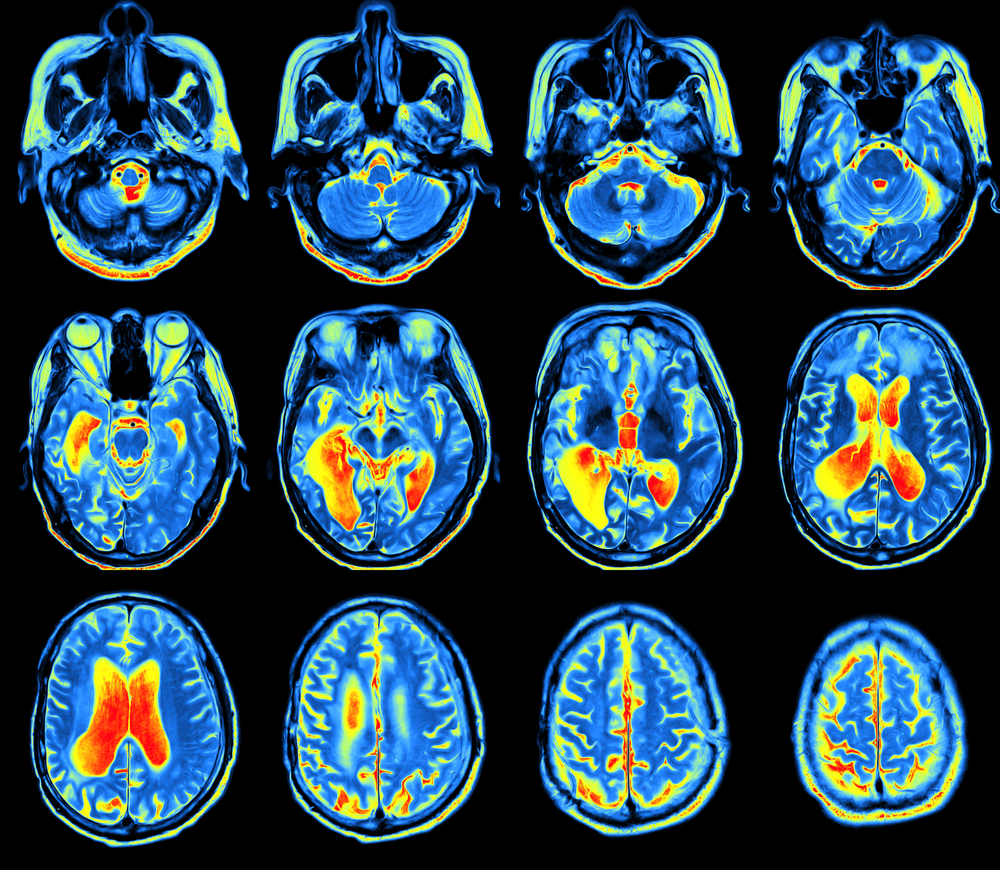

Researchers assessed 24 Parkinson’s patients on and off dopaminergic medication and 24 healthy controls who performed a learning task while undergoing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The Parkinson’s Disease News Today forums are a place to connect with other patients, share tips and talk about the latest research. Sign up today!

In the first stage of the experiment — the learning phase — participants gradually learned to make better choices regarding three fixed pairs of stimulus options according to how well they were rewarded (reward feedback).

In the second stage — the transfer stage — participants used their learning phase experience to guide their choices when presented with new combinations of options, without receiving any further feedback.

The decisions during the transfer phase were examined using an approach/avoidance framework.

Additionally, researchers developed a model-based fMRI analysis, which they used to examine medication-related changes in blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) brain signals in response to reward prediction error during learning.

Blood-oxygen-level dependent imaging, or BOLD-contrast imaging, is a method used in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to observe different areas of the brain or other organs, which are found to be active at any given time.

Results indicated that, during learning, medication use in Parkinson’s patients reduced an overemphasis on negative outcomes. Hence, patients tended to be less concerned with negative outcomes.

This finding is similar to other studies that show “a [dopamine] medication-driven impairment in behavioral responses relating to negative feedback.”

The shift toward lower sensitivity to negative outcomes in Parkinson’s patients on medication reflects a partially restorative effect of the medication, as sensitivity to negative outcomes became more similar to that observed in healthy controls.

These behavioral adaptations were tied to BOLD changes in the dorsal striatum (the area of the brain directly related to decision-making).

“Medication-induced shifts in negative learning rates were predictive of changes in approach/avoidance choice patterns after learning, and these changes were accompanied by striatal BOLD response alterations,” investigators said.

“These findings highlight dopamine-driven learning differences in PD and provide new insight into how changes in learning impact the transfer of learned value to approach/avoidance responses in novel contexts,” they concluded.