Dopamine Transporter Levels May Predict Parkinson’s Earlier

Written by |

Lower levels of dopamine transporter protein in the striatum — a brain region affected significantly in Parkinson’s — may predict the development of the neurodegenerative disease up to eight years earlier in older adults carrying the most common genetic risk factor, a small study suggests.

However, the observed variability in the rate of decline in dopamine transporter protein (DaT) over time, even in the same individual, may limit its use as a biomarker or a predictor of conversion to Parkinson’s in this high-risk population, the researchers noted.

Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings and validate the predictive value of DaT levels in the pre-motor stage of the disease. the researchers added.

The study, “Serial DaT-SPECT imaging in asymptomatic carriers of LRRK2 G2019S mutation: 8-years follow-up,” was published in the European Journal of Neurology.

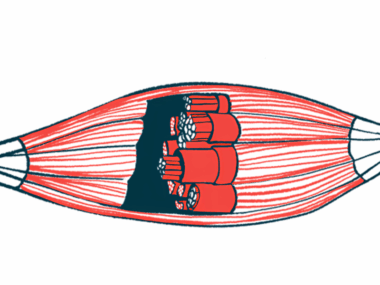

Parkinson’s disease is characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons — those producing dopamine, one of the major chemical messengers in the brain — and dopamine signaling in the substantia nigra and the striatum, two brain regions involved in the control of voluntary movement.

The onset of dopaminergic neuron loss in Parkinson’s “is estimated to antedate [precede] the appearance of parkinsonism by 5–15 years, however studies analyzing the rate of nigrostriatal dysfunction during this phase are scarce,” the researchers wrote. Of note, nigrostriatal refers to the pathway that connects the substantia nigra with the striatum.

“Understanding this stage and identifying potential biomarkers to track it is crucial to design clinical trials with neuroprotective [therapies] applied at early phases,” the researchers stated.

Studying asymptomatic people carrying the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 gene — the most common mutation associated with Parkinson’s — can help identify potential biomarkers or predictors of Parkinson’s development. Notably, only a proportion of LRRK2-G2019S mutation carriers will develop motor symptoms of Parkinson’s.

Now, a team of researchers in Spain evaluated whether clinical examination, olfaction testing, and striatal DaTscan at first assessment (baseline) could predict conversion to Parkinson’s after four and eight years in 32 adults, aged about 58 years, carrying the LRRK2-G2019S mutation, and not showing symptoms.

Motor function was evaluated through the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III), and sense of smell was evaluated through the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Of note, reduced smell has been investigated previously as a potential predictive biomarker in this high-risk population.

DaTscan is a type of non-invasive single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging technique that helps visualize dopamine transporter levels in the brain, which also are progressively lost in Parkinson’s.

Notably, DaTs are typically found at the outer membrane of dopaminergic neurons, helping to determine the density of healthy dopamine-producing neurons in a patient’s brain.

A total of 25 participants underwent all four-year assessments and their data were reported in a previous study. Seventeen of these adults, with a mean age of 62.5 years, completed the eight-year assessment.

No differences in age, sex distribution, and baseline UPDRS-III scores were detected between those who completed the eight-year assessment and those who did not.

Results showed that three participants developed Parkinson’s disease at four years and one participant converted to Parkinson’s between the four- and eight-year assessment, indicating that 16% of the mutation carriers followed for up to eight years developed the disease.

There was a significant increase in UPDRS-III scores from baseline to eight years, highlighting the presence of greater motor difficulties, while age-adjusted sense of smell remained largely stable over time.

Notably, those who developed Parkinson’s had fewer striatal DaTs at baseline than non-converters, suggesting that striatal DaTscan values in LRRK2-G2019S mutation carriers without symptoms may help predict conversion to Parkinson’s up to eight years before.

The levels of striatal DaTs dropped significantly over time, with a mean annual rate of 3.5%, “indicating progressive nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction,” the researchers wrote. This decline was significantly more pronounced in the first four years of follow-up than in the four- to eight-year period (mean drop of 21.3% vs. 8.3%).

While a DaTscan value below one was a good predictor of Parkinson’s development within the first four years of follow-up (three of three participants), only one out of four adults with values below one at four years converted to Parkinson’s at eight years.

“The lower slope of [DaT] decline in the 4 to 8-year period most likely prevented them from reaching a critical threshold at which the motor manifestations would have appeared,” the team wrote.

This DaTscan critical threshold was found to range between 0.5 and 0.8, as no mutation carrier showing values above this threshold developed Parkinson’s motor symptoms.

Also, while both older age and male sex were associated with fewer striatal DaTs, neither factor influenced the rate of decline in DaTscan values.

These findings “may contribute to clarify the utility and limitations of DaT-SPECT as a biomarker of the premotor stages of PD,” the researchers wrote, adding that DaTscan values appear to predict Parkinson’s conversion.

However, “the observed intra-individual variability of DaT binding decline overtime may prove to be an obstacle to its use as a biomarker or as a predictor of [Parkinson’s conversion],” the team concluded.