Device lets Parkinson’s patients track their own motor symptoms

Finger taps provide data doctors can use between 'infrequent' visits

Written by |

Stanford University researchers developed a simple, portable device that allows Parkinson’s disease patients to monitor their motor symptoms remotely, in real time, providing their doctors with updated information that can be used to guide treatment decisions.

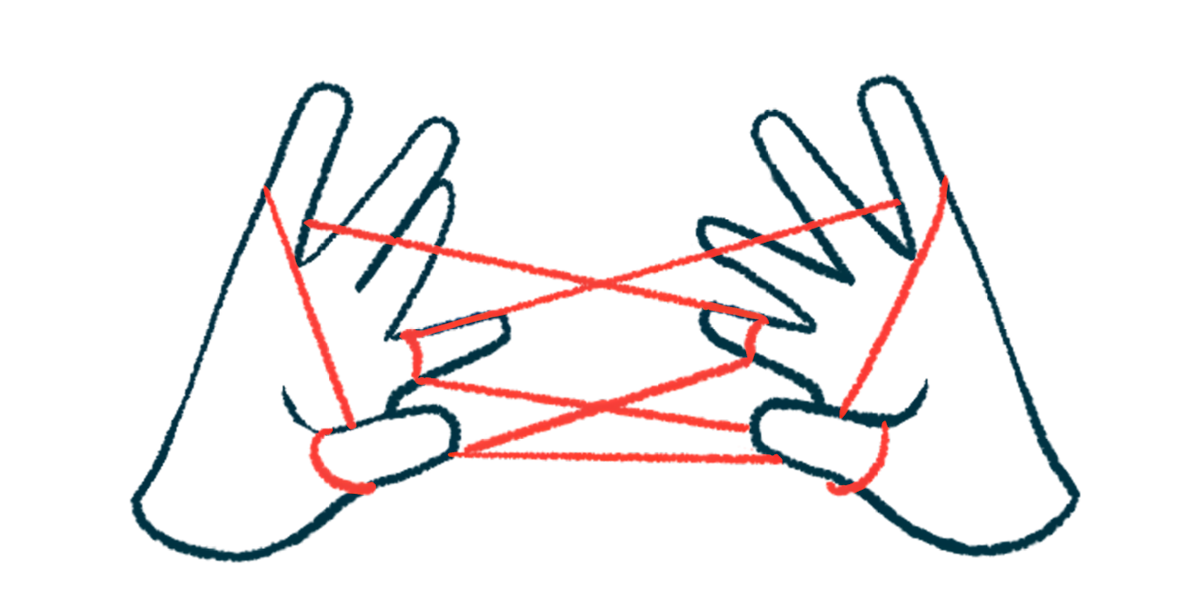

Patients tap alternating fingers for 30 seconds on the two-lever device, called KeyDuo, which pairs with a smartphone-connected platform to translate high-resolution details into data that clinicians can use.

The researchers described the device in a study, “Remote real time digital monitoring fills a critical gap in the management of Parkinson’s disease,” published in npj Parkinson’s Disease.

KeyDuo “allows a physician to better manage patients between infrequent in-person visits — and it creates a rich set of data points for a physician to assess motor outcomes and potential trends,” Helen Bronte-Stewart, MD, the study’s senior author and a professor at Stanford Medicine, said in a university news story. “Patients suddenly have more frequent interactions with their provider by using this tool remotely.”

Patients ‘fend for themselves’ between appointments

In Parkinson’s, certain brain cells gradually die off, giving rise to a characteristic set of motor symptoms: slowed movements, rigidity, and tremor.

People with Parkinson’s are usually assessed in person every three to six months. But as the disease progresses, a treatment plan provided by the neurologist at one visit may be insufficient by the next.

“We know that only about 40% of patients with Parkinson’s ever see a neurologist, and many of those go months between appointments,” Bronte-Stewart said. “It is desperately difficult for people to get care, and they are often left to fend for themselves and manage their own medications.”

The number of neurologists trained to administer the standard Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) to evaluate symptom changes is limited, and “the supply of physicians who feel comfortable managing the condition is very small,” Bronte-Stewart said.

KeyDuo measures the force of a patient’s taps on the levers, the speed at which the lever moves, and the extent of its downward movement. The results are transmitted to clinicians in real time.

To assess KeyDuo’s feasibility and clinical relevance, the team recruited 30 adult Parkinson’s patients with varying lengths of disease duration, from those with suspected Parkinson’s to patients who had had the disease for 20 years. Participants’ symptoms were well controlled with Parkinson’s medications and/or deep brain stimulation.

Most of the patients with established disease (84.2%) said they didn’t have a monitoring method for their symptoms, and either didn’t track their symptoms or tracked them mentally. About half (52.6%) said they were assessed by their neurologist for motor symptoms using the MDS-UPDRS no more than twice a year, with 15.8% seeing their neurologist no more than once a year.

Participants were first trained on the system. Starting with the right hand, then followed by the left, they were told to fully press and release the levers with their index and middle fingers in an alternating fashion, tapping as fast as possible.

A total of 25 people competed the 30-day study. Participants demonstrated excellent compliance with remote testing, with 96.2% completing one test per day and 82.2% two tests per day, the researchers said.

KeyDuo mobility scores significantly correlated with results from the MDS-UPDRS part 2, a standard assessment that measures motor experiences of daily living.

A recent study by Bronte-Stewart and colleagues showed that both the timing and strength of lever pushes on the device could identify Parkinson’s-related tremors with an accuracy of 98%. “This is something that has been incredibly hard to capture in the past, even in clinical exams,” Bronte-Stewart said.

In the current study, the team found that KeyDuo revealed progression from early symptoms affecting one side of the body to severe deficits affecting both sides of the body.

Recorded progressive disease events included freezing, irregular movements, lower tapping strength and frequency, and differing performances between the two fingers.

KeyDuo was also able to detect effects of small, patient-initiated increases or decreases in the dose of Parkinson’s medications during remote monitoring.

“The results with this [device] are objective and validated,” Bronte-Stewart said. “It will allow people to manage their medicines more carefully and allow health care providers to look after people between these rare visits.”

KeyDuo can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of investigational Parkinson’s medications in clinical trials, Bronte-Stewart said. “You’ll be able to get data for an early-stage therapeutic in much less time, with fewer participants and at reduced cost,” she said.