Gut Bacteria May Cause Constipation Associated With Levodopa in Parkinson’s Patients

Written by |

Scientists found a species of bacteria living in the small intestine, called Clostridium sporogenes, that is able to convert a fraction of unabsorbed levodopa — a medication commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease — into a chemical that lowers gastrointestinal mobility.

According to authors, this process may worsen constipation, one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms seen in patients with Parkinson’s. They also noted that understanding how C. sporogenes accomplishes this task should make it easier to find ways to prevent it.

Their findings were reported in the study “Gut bacterial deamination of residual levodopa medication for Parkinson’s disease,” published in the journal BMC Biology.

Levodopa is one of the main medications used to treat tremors, stiffness, and slowness of movement in patients with Parkinson’s. It is absorbed in the small intestine; from there it travels to the brain where it is converted to dopamine, the brain chemical that is progressively lost over the course of the disease.

However, not all levodopa reaches the brain. Previous studies indicated that 8–10% of the medication that is not absorbed right away may travel farther to a lower portion of the intestine. Once there, these levodopa residues may come into contact with certain species of bacteria that can process and convert them into other chemicals.

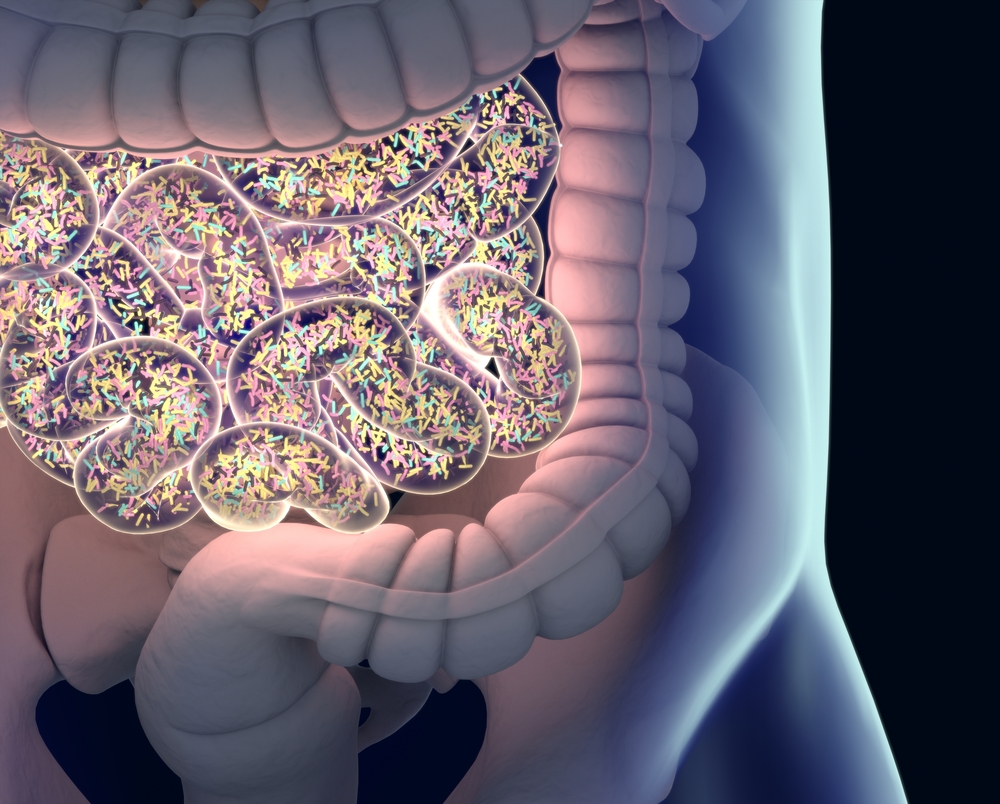

Researchers from the University of Groningen, Netherlands, and their colleagues wondered if these bacteria could explain why gut transit is slower in patients with Parkinson’s compared with healthy individuals. They wondered if levodopa was being broken down — metabolized — by these bacteria into certain compounds that slowed intestinal mobility.

To explore this idea, they placed a culture of C. sporogenes — a bacteria of the small intestine known to metabolize compounds similar to levodopa through a process called deamination (removal of an amino group from a molecule) — in contact with levodopa for 48 hours.

They observed bacteria were able to fully metabolize levodopa within a period of 24 hours, converting it into a compound called DHPPA.

The team then performed a series of experiments to identify the enzyme responsible for the first step of the deamination process. Their findings suggested this was mediated by an aminotransferase, or transaminase enzyme, called EDU38870.

“This process involves four steps, three of which were already known. However, we uncovered the initial step, which is mediated by a transaminase enzyme,” Sahar El Aidy, PhD, the study’s senior author, said in a press release.

The team’s next goal was to test whether DHPPA could affect intestinal mobility and gut transit.

To answer this question, they made small portions of mouse small intestine contract by putting them in contact with the neurotransmitter (brain signal messenger) acetylcholine. They then exposed these intestinal sections to either levodopa or DHPPA.

Intestinal contractions slowed down only in the sections that had been exposed to DHPPA. In this scenario, contractions decreased by 69% within five minutes and by 73% after 10–15 minutes.

To assess the relevance of these findings to patients with Parkinson’s, researchers compared the levels of DHPPA found in patient stool samples and in those of healthy people who were on a similar diet.

“Because [DHPPA] is also produced as a breakdown product of coffee and fruits, we compared samples from patients with those from healthy controls with a comparable diet,” El Aidy said.

Analyses showed that stool samples from patients with Parkinson’s who were actively taking levodopa contained higher levels of DHPPA compared with those from healthy controls. Additional experiments also showed bacteria found in patient stool samples were able to metabolize levodopa into DHPPA, confirming the high levels of DHPPA seen in these samples were a direct result of this process.

“Overall, this study underpins the importance of the metabolic pathways of the gut microbiome involved in drug metabolism not only to preserve drug effectiveness, but also to avoid potential side effects of bacterial breakdown products of the unabsorbed residue of medication,” investigators wrote.

According to El Aidy, the fact that a patient’s own gut bacteria can metabolize levodopa into a substance that potentially worsens constipation, one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms associated with the disease, is unfortunate.

“However, now that we know this, it is possible to look for inhibitors of the enzymes in the deamination pathway identified in our study,” she said.