Lowering Level of Protein Could Prevent Mutation From Triggering Parkinson’s, Study Suggests

Written by |

Lowering the level of a certain protein can prevent PINK1 gene mutations from triggering an inherited type of Parkinson’s disease (PD), according to a study.

The research may provide new insights into the role of fat molecules in neurons — particularly those inside energy-creating mitochondria — in Parkinson’s. The disease is a progressive disorder of the nervous system that affects movement.

Since treatments targeting the FASN (fatty acid synthase) protein are already being developed in the lab for cancer and other diseases, Parkinson’s applications could be possible as well, researchers said.

The study, “Cardiolipin promotes electron transport between ubiquinone and complex I to rescue PINK1 deficiency,” was published in the Journal of Cell Biology.

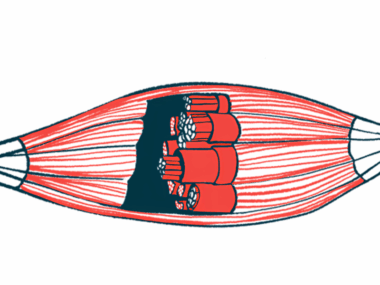

PINK1 mutations cause early-onset Parkinson’s disease by decreasing levels of a fat molecule called cardiolipin in mitochondria, cells that produce energy. Lack of cardiolipin disrupts mitochondria processes, leading to cell death.

Researchers at the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology — VIB in Belgium did a large genetic screening showing that lowering FASN levels prevented abnormalities triggered by the mutations.

The team tested their discovery in fruit flies, mouse cells, skin cells taken from patients, and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopamine neurons. Although FASN is not located in mitochondria, researchers found that lowering its levels increases levels of cardiolipin in mitochondria.

“Several drugs that block FASN already exist, as this protein is also important to cancer research and treatment,” Patrik Verstreken, a professor at VIB and the study’s senior investigator, said in a press release. “Many of them have already been used in clinical trials. Thanks to this research, we can now test them in the context of Parkinson’s disease.”

The research team is now focusing on projects that help them better understand the relationship between specific types of lipids, or fats, in nerve cells and Parkinson’s disease.

“Some questions need to be answered before new therapies can be developed, such as ‘is there a link between early onset Parkinson’s prevalence and progression with lipid content?’ And while we successfully demonstrated that cardiolipin can improve the function of mitochondria in flies, mouse models and in human cells, we need to explore its effects in actual patients,” Verstreken said.