Brain Recordings in Parkinson’s Patients Advance Knowledge of Disease Mechanisms

Scientists have recorded the activity of nerve cells in the brains of human patients with Parkinson’s disease in what is believed to be the first time, focusing on the brain region where neuronal loss leads to movement and cognitive symptoms typical of the condition — the striatum.

The study, “Human striatal recordings reveal abnormal discharge of projection neurons in Parkinson’s disease,” recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides a significant advancement in the understanding of how changes in this brain region contribute to Parkinson’s development.

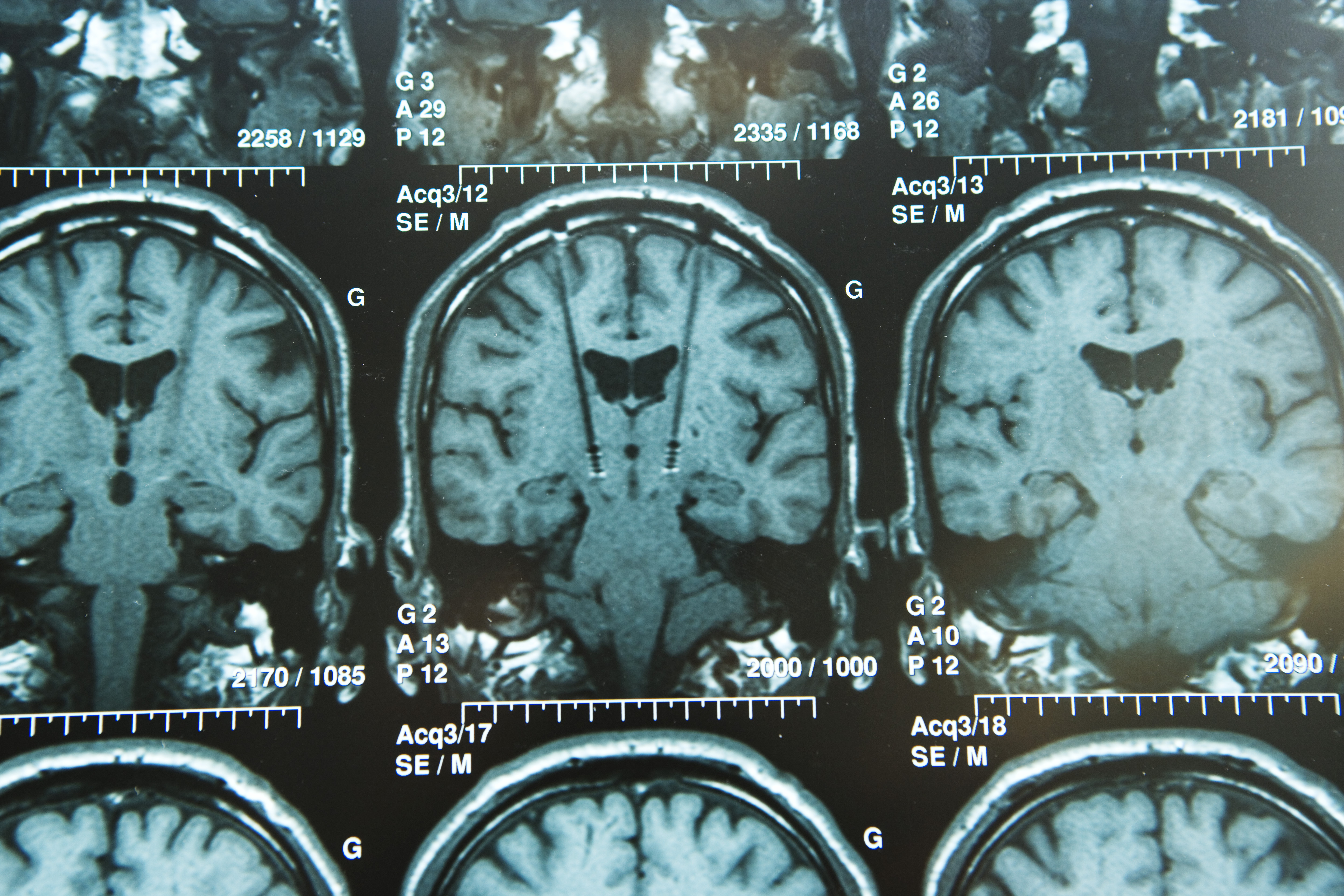

Scientists have long explained Parkinson’s disease with a model stating that the breakdown of dopamine neurons in a brain area called the striatum affects the behavior of other neurons in the region. While animal research has supported the model, it has so far been impossible to prove the changes take place in human patients. Until now, the only available method to study nerve cells has been through brain imaging, a rather blunt tool that produces conflicting results.

The research team at Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University did not hurry the study — it took them years to carefully select Parkinson’s patients, undergoing surgical deep brain stimulation treatment, to collect enough brain recordings.

The technique used by the research team has been used to study how neurons fire in the brain of animals. Since it takes an electrode to be inserted into the brain, the method has not been suitable for studying people. At least, not until Parkinson’s patients started receiving a treatment called deep brain stimulation, based on having an electrode implanted in the brain.

The team compared brain recordings from the striatum of Parkinson’s patients with those treated with deep brain stimulation for dystonia and essential tremor.

Researchers noted that striatal projection neurons — a cell type that is disrupted in animal models of Parkinson’s — fired at much higher frequency with common bursts of nerve cell activity in Parkinson’s compared to the other patients. Researchers also saw the same differences in brain recordings from two groups of non-human primates, of which one had been treated with a toxic compound triggering Parkinson’s.

“We found profound changes in the activity of striatal projection neurons in patients with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Stella Papa, MD, senior author of the study, said in a news release, adding that researchers have been seeking this data to help understand Parkinson’s disease.

Papa and her research team are now focusing on the steps causing neurons to misbehave, which they think is key to developing new Parkinson’s treatments.