Onset of Parkinson’s Disease May Be Slowed by Metabolite in MS Drug, Mouse Study Shows

Dimethylfumarate (Tecfidera), a drug used to harness multiple sclerosis symptoms, generates a metabolite that could be used in Parkinson’s patients to improve defenses against oxidative damage. The drug acts on Nrf2, a molecule that has frequently been suggested as a target for neuroprotective drugs in Parkinson’s, as its activation is a part of our natural defense against oxidative stress and inflammation.

The multiple sclerosis drug was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2013, and its ability to activate Nrf2 is known by scientists. But some of its side effects, including flushing, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and brain dysfunction has made the drug particularly unsuitable for patients with Parkinson’s disease, who often have gastrointestinal problems caused by their disease.

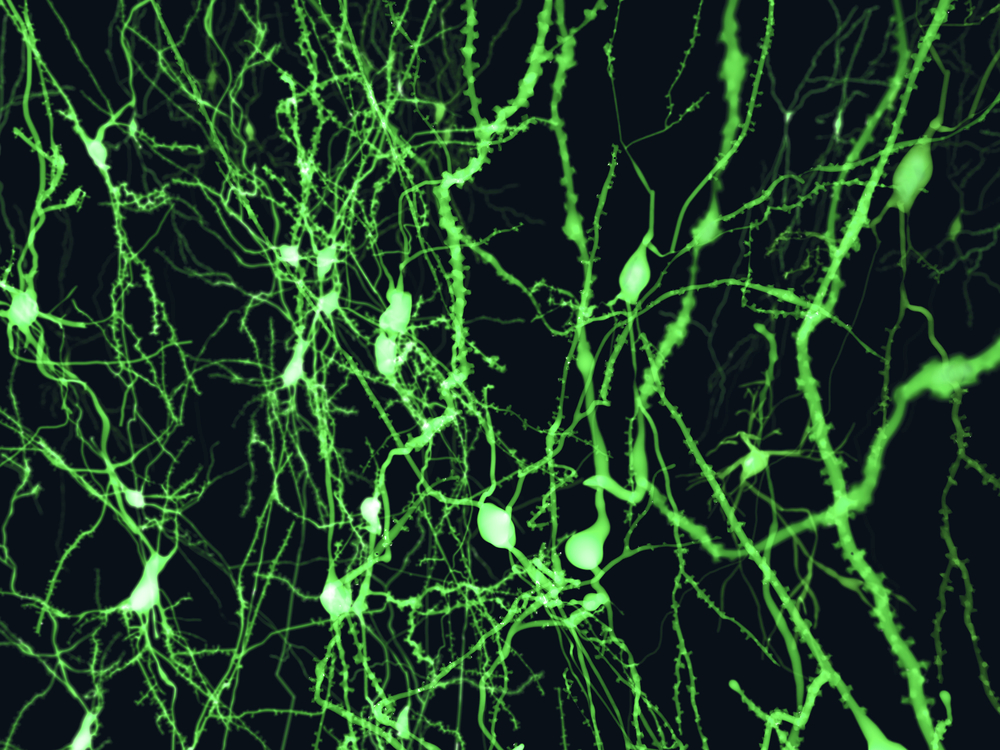

Such problems are linked to the death of dopamine neurons also in the gut, and as is the case with other movements, the lack of the neurotransmitter prevents gut motility, effectively causing constipation. The metabolite of dimethylfumarate, called monomethylfumarate, is also known to activate Nrf2, but is not as potent. It also turned out to be less toxic.

Researchers from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University decided to tease out the individual contributions of the drug and its metabolite, and discovered that both substances activated Nrf2, but in contrast to its parent drug, monomethylfumarate had a range of effects further promoting neuroprotection.

The study, “Distinct Nrf2 Signaling Mechanisms of Fumaric Acid Esters and Their Role in Neuroprotection against 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinson’s-Like Disease,” demonstrated that while dimethylfumarate depleted the anti-oxidant glutathione, decreased cell survival, and blocked the capacity of mitochondria to use oxygen and glucose to make energy, initially exposing cells to a more stressed state, its metabolite triggered the opposite changes, reversing the harmful situation the parent compound induced.

These changes were observed in cultured cells, so to study the impact of the two compounds on a living organism, the research team treated mice with a toxin called MPTP, capturing the progression of Parkinson’s disease on a short time scale. Mice exposed to the toxin lose dopamine neurons and develop symptoms within days.

The report, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, showed that mice that received either dimethylfumarate or its metabolite before they were given the toxin were largely protected against the neurodegenerative effects, also showing fewer signs of inflammation and oxidative stress. If, however, the same procedure was applied in mice lacking the Nrf2 gene, the toxin wiped out the dopamine neurons, showing that activation of Nrf2 is a key part of this neuroprotection.

While dimethylfumarate is a more potent drug, the team showed that its metabolite is good enough in protecting from neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s, activating Nrf2 in a more direct manner.

The research team now wants to bring these findings to the clinic, awaiting the formulation of monomethylfumarate and other substances mimicking its structure, for humans.

“If we can catch them early enough, maybe we can slow the disease,” co-author Dr. John Morgan, a neurologist and Parkinson’s disease specialist, said in a news release. “If it can help give five to eight more years of improved quality of life, that would be great for our patients.”