Future of Parkinson’s Therapy Might Be in Unfertilized Human Egg Cells, Researchers Say

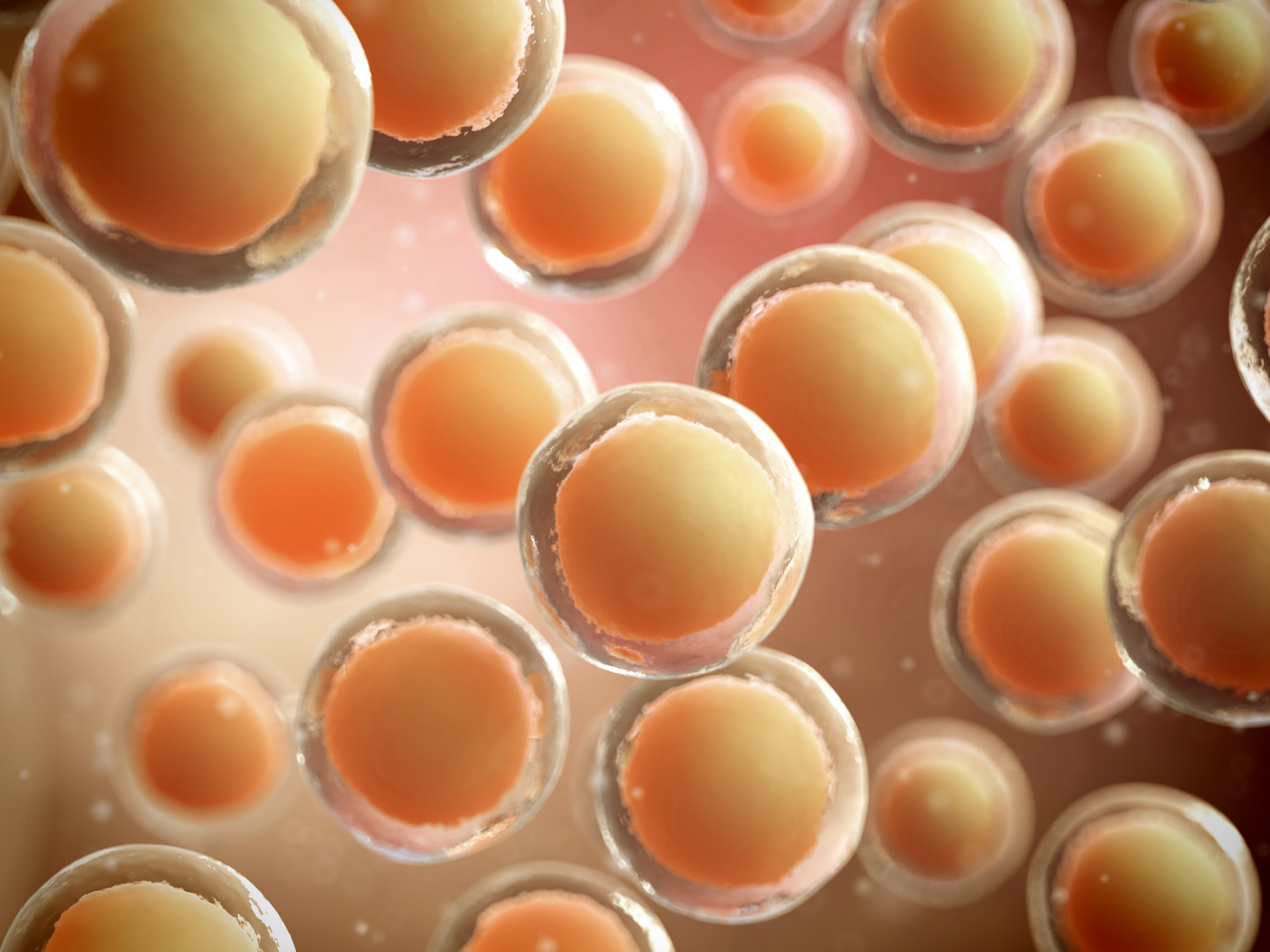

Unfertilized human egg cells can give rise to so-called parthenogenetic stem cells, having the characteristics of embryonal stem cells but without the ethically debatable use of early embryos. Now, a new study demonstrates that neural stem cells derived from parthenogenetic cells transplanted to non-human primates with Parkinson’s disease improved symptoms and increased dopamine signaling in the animals’ brains.

Parthenogenetic stem cells were developed by the International Stem Cell Corporation, which is also behind the new Parkinson’s-related study. By chemically forcing the cells to start dividing, the use of fertilized early embryos is done away with, making these cells an ethically superior option.

Another benefit of the technique is that, for female patients, stem cells can be produced from the woman’s own egg cells, producing cells that the immune system will not recognize as foreign. For those without this possibility, it is still possible to develop stem cells that are compatible with a large part of the population.

The monkeys used in the study — which was a collaboration between the International Stem Cell Corporation and a number of prominent U.S. institutions — all had moderate to severe Parkinson’s disease.

Titled “Neural Stem Cells Derived from Human Parthenogenetic Stem Cells Engraft and Promote Recovery in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Parkinson’s Disease,” the study describes the procedure of directly injecting human parthenogenetic stem cell-derived neural stem cells into the striatum and substantia nigra of the animals’ brains — two areas primarily affected by neurodegenerative changes in Parkinson’s disease.

The research team then followed the animals for 12 months, closely monitoring them for side effects of the treatment. Researchers report in the journal Cell Transplantation that the treatment was well tolerated and did not give rise to dyskinesia, tumors, formation of tissue in abnormal places, or other serious adverse events related to the transplantation. One of the 18 animals, however, died from bleeding inside the brain.

The treatment also lessened symptoms and improved behaviors related to disease, although the difference from the control animals was not statistically significant. When looking at disease trajectories, the research team observed that animals receiving low doses of stem cells had fewer symptoms at the end of the 12-month period and improved disease course.

In addition, the animals receiving a low-dose treatment had higher levels of dopamine, correlating with fewer symptoms. There were also more dopamine neurons and more connections between neurons in the low-dose treated animals.

“The use of neural stem cells derived from human parthenogenetic cells may be a new avenue for treating a variety of conditions,” said Dr. Paul Sanberg, co-editor-in-chief of Cell Transplantation and distinguished professor at the University of South Florida.

“The study showed evidence of safety in using these cells, which is an improvement upon previous stem cell therapies that have shown some lineages may result in tumor formation. A follow-up study that further assesses the clinical potential of this approach for functional improvement may prove promising in future treatments for Parkinson’s disease.”

While earlier cell therapy trials have produced variable results — with some studies showing excellent outcomes for up to 18 years and others failing to demonstrate a significant improvement or were plagued with adverse events — the current data using neural stem cells derived from unfertilized human egg cells are strong enough to support a human Phase 1/2a clinical trial, testing the safety of the cells in Parkinson’s patients.