Genetic Factors May Contribute to Young-onset Parkinson’s, Study Suggests

Written by |

[Parameter-Settings] FileVersion = 2000 Date/Time = 0000:00:00 00:00:00 Date/Time + ms = 0000:00:00,00:00:00:000 User Name = TCS User Width = 1140 Length = 956 Bits per Sample = 8 Used Bits per Sample = 8 Samples per Pixel = 3 ScanMode = xy Series Name = 04.16.12.lei

People who develop Parkinson’s disease before the age of 50 may have been born with the defective brain cells responsible for causing the illness, a study suggests.

These results also reveal that a medicine, which is already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating pre-cancers of the skin, may be able to prevent the progress of the disease by interfering with several pathways related to Parkinson’s disease.

The study, “iPSC modeling of young-onset Parkinson’s disease reveals a molecular signature of disease and novel therapeutic candidates,” was published in the journal Nature Medicine.

In Parkinson’s disease, neurons that make dopamine — a neurotransmitter crucial for coordinating movement and regulating mood — start to die, causing a decrease in the amount of dopamine in the brain.

Often, exactly what is causing the neurons to die is not known, although the accumulation of toxic forms of the alpha-synuclein protein into clumps known as Lewy bodies is a possible culprit.

Most Parkinson’s patients get diagnosed when they are older than 60, but in 10% of cases, individuals are between 21 and 50 years old, referred to as young-onset Parkinson’s. More than 80% of these young patients do not have a family history of the disease, and none of the known Parkinson’s mutations are present in their DNA.

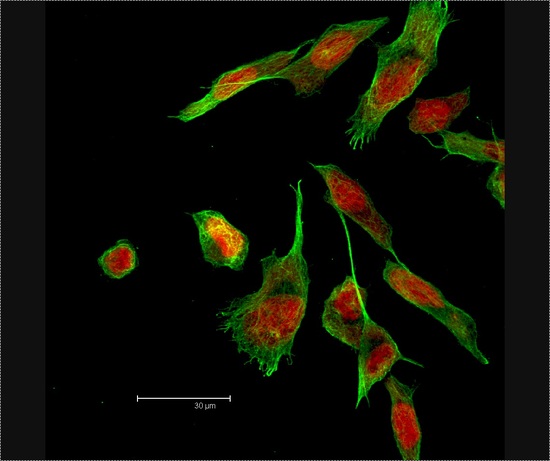

In this study, researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to study young-onset Parkinson’s disease.

iPSCs are a special type of stem cell that can be produced in the lab by using adult cells from a patient donor and reverting them back to a stem cell-like state. These cells then have the potential to develop into almost any type of cell in the body, similar to stem cells in an embryo.

The iPSC technique was used to convert blood cells from patients with young-onset Parkinson’s and no family history of the disease, as well as healthy volunteers, used as controls, into dopamine-producing neurons. Donor patients had no known Parkinson’s disease-related mutations.

“Our technique gave us a window back in time to see how well the dopamine neurons might have functioned from the very start of a patient’s life,” Clive Svendsen, PhD, a professor at Cedars-Sinai and senior author of the study, said in a press release.

The researchers noticed three key features in the iPSC-derived dopamine neurons from Parkinson’s patients that could be used to predict or diagnose new cases.

First, these nerve cells had higher levels of alpha-synuclein, a common occurrence in most forms of Parkinson’s. Second, lysosomes (structures in the cell used to capture and break down waste products) did not seem to be functioning properly, which could contribute to the buildup of alpha-synuclein. And third, levels of the protein kinase C (an enzyme that controls the function of other proteins in the cell) were higher than normal.

These findings indicate that young-onset Parkinson’s disease has a genetic contribution rather than occurring randomly as previously thought. This molecular signature had a 96% sensitivity in correctly identifying patients with early-onset disease.

Researchers hypothesized that the acute increase in alpha-synuclein does not cause dopamine neuron death in these patients. Instead, “an inability to degrade [alpha]-synuclein over many years leads to accumulation of insoluble [alpha]-synuclein in dopaminergic neurons, cellular death and Lewy body formation,” they wrote in the study.

“What we are seeing using this new model are the very first signs of young-onset Parkinson’s,” Svendsen said. “It appears that dopamine neurons in these individuals may continue to mishandle alpha-synuclein over a period of 20 or 30 years, causing Parkinson’s symptoms to emerge.”

Lysosome dysfunction could be a major contributor to Parkinson’s, according to the researchers. As such, they tested the effectiveness of different compounds known to activate lysosomes in the patient-derived dopaminergic neurons, in the hope that excess alpha-synuclein would get broken down.

A compound called PEP005, approved by the FDA for pre-cancers of the skin, was able to lower the levels of alpha-synuclein in these neurons. When injected into the brains of mice, PEP005 also significantly decreased alpha-synuclein levels.

Surprisingly, this compound reduced the levels of alpha-synuclein by activating another protein breakdown pathway, called proteasomal degradation, rather than lysosome degradation as initially expected.

PEP005 also worked by increasing the amount of tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme involved in the production of dopamine and whose deficiency has previously been linked to Parkinson’s.

Additionally, PEP005 lowered the levels of a specific type of protein kinase C. This is the first-time protein kinase C has been linked to Parkinson’s, so more research is needed to understand its exact role in this disease. The team now plans to validate protein kinase C as a marker of the disease by measuring the amount present in brain tissue sample from donor patients.

Because PEP005 is currently available as a gel that can be applied to the skin, a way to efficiently deliver it to the brain will need to be investigated to potentially develop it into a successful Parkinson’s treatment.

“Young-onset Parkinson’s is especially heartbreaking because it strikes people at the prime of life,” said study author Michele Tagliati, MD, professor in the Department of Neurology at Cedars-Sinai. “This exciting new research provides hope that one day we may be able to detect and take early action to prevent this disease in at-risk individuals.”