Dopamine Therapy for Parkinson’s May Be Possible Using Neurons Transplants with On and Off Switches

Written by |

Therapies intending to increase dopamine levels in the brains of Parkinson’s patients have struggled to adequately regulate signaling. But researchers have now engineered transplant dopamine neurons that might be switched on or off using designer drugs — suggesting these transplants might be a viable way of treating Parkinson’s via dopamine release after all.

Attempts to improve the dopamine deficit in Parkinson’s using both drug approaches and, more recently, transplanted dopamine neurons made from stem cells, have one thing in common — all have failed to trigger just the right amount of dopamine release, leading either to lingering symptoms or intolerable side effects. Dopamine, a brain chemical, is essential for coordinated movement.

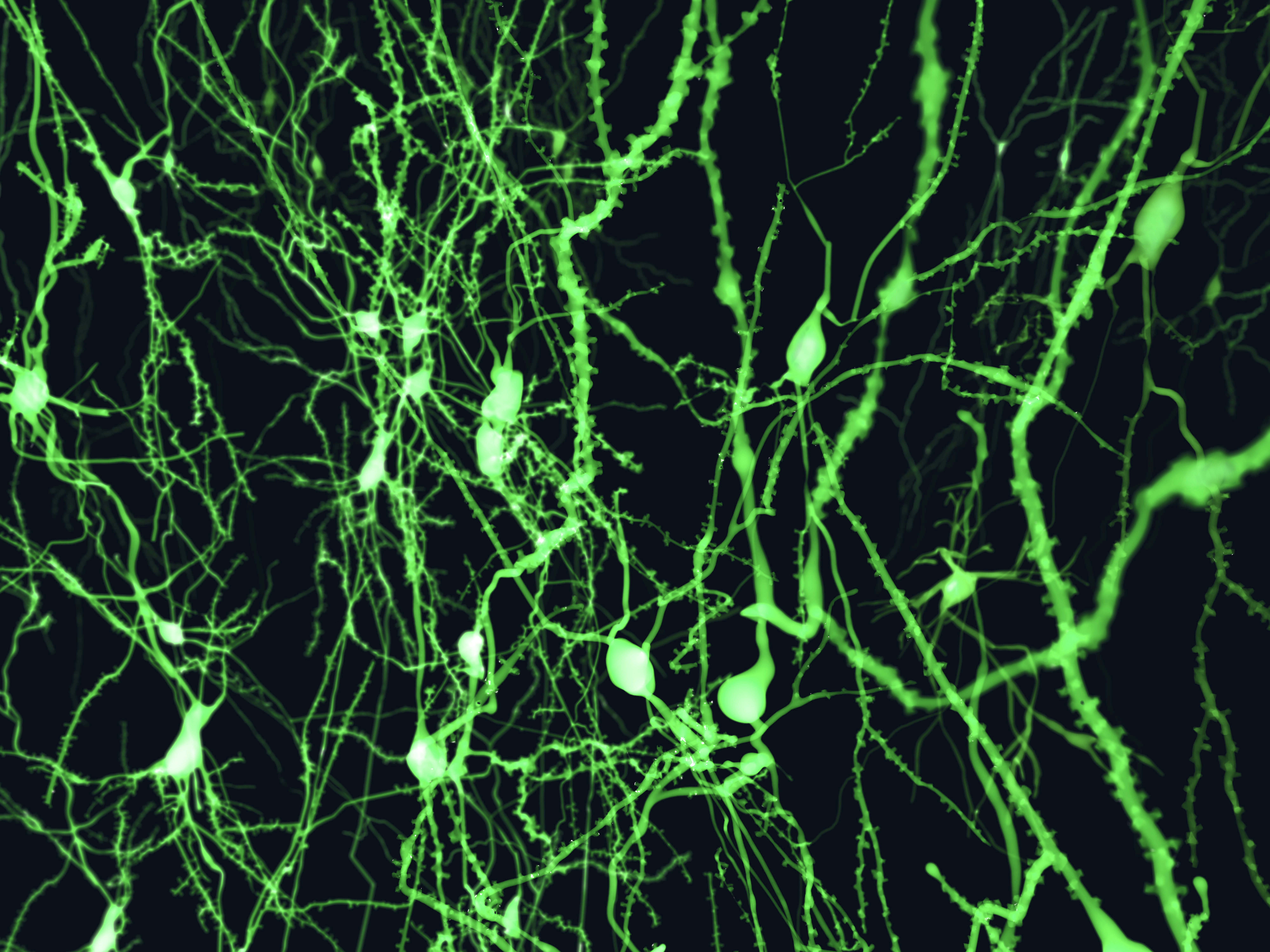

In an effort to solve this problem, researchers at University of Wisconsin at Madison Waisman Center used embryonal stem cells to produce two types of dopamine neurons in the lab. The study, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, showed that the cells differed in one important aspect from previous ones — they held receptors for two types of drugs that can either turn on or off dopamine release.

Testing the cells in mice, researchers found that the drug-induced switches seemed to work as intended. “I’m a neuro guy, and the Parkinson’s disease model is very well established in mice – you can measure the outcome in their behavior. If the animal recovers, it must be due to the secretion of dopamine from the transplanted cell,” Su-Chun Zhang, the paper’s senior author, said in a press release.

The study, “Chemical Control of Grafted Human PSC-Derived Neurons in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease,” might have wider applications, according to Zhang, a professor of neuroscience at the Waisman Center who once pioneered the development of neurons from embryonic stem cells. “This is the first proof of principle, using Parkinson’s disease as the model, but it may apply to many other diseases, and not just neurological diseases,” he said.

The engineering of the cells employed what is known as the CRISPR gene editing technique, able to cut DNA, and insert new genes, in a more precise manner than was previously possible.

Earlier attempts to transplant cells that produced dopamine could not be regulated adequately, and have not reached clinical use. “If we are going to use cell therapy, we need to know what the transplanted cell will do. If its activity is not right, we may want to activate it, or we may need to slow or stop it,” Zhang said.

Receptors used to control the cells do not exist on other cell types in the body, reducing the risk of side effects. Researchers also believe it possible to design cells holding both an ‘on’ and ‘off’ switch in the same cell. But before any clinical trials might become reality, several issues need to be resolved, such as confirmation that both cells and drugs are safe to use in humans.

It is also necessary to test the transplanted cells in primate animal models. “We need to prove that this is not just a mouse phenomenon,” Zhang says, “that this really works to alleviate the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.”