Parkinson’s May Impair Perception of Movement in Abstract Art

Written by |

People with Parkinson’s disease have an altered perception of movement when viewing abstract art as compared with their age- and education-matched healthy peers, a study found.

These results suggest that motor responses, aesthetic appreciation, and motion are somehow linked — and that altered neurological function, such as that observed in Parkinson’s patients, can change the way that art is perceived.

“People can experience movement in abstract art, even without implied movement, like brush strokes,” Anjan Chatterjee, MD, the study’s last author and a professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, said in a university press release.

“These representations of movement systematically affect people’s aesthetic evaluations, whether they are healthy individuals or people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Chatterjee, also the director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics.

Cognitive neuroscience can “provide clues about how viewing art affects our neural systems,” the university said.

The study, “Movement in Aesthetic Experiences: What We Can Learn from Parkinson’s Disease,” was published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience.

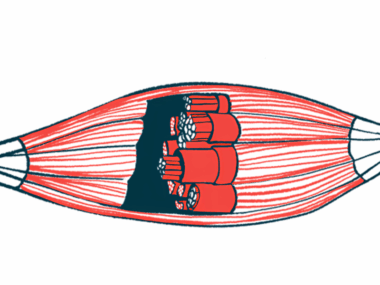

Different aesthetic experiences engage separate neural systems that represent varying types of information, such as perceptual, motor, or emotional. Visual art thus can allow researchers to study how subjective value is constructed from interactions between several neural systems.

Here, the Penn Medicine researchers assessed the aesthetic experiences of 43 patients with Parkinson’s disease.

The patients, who had a mean age of 67.8, were part of a long-term study wherein they underwent cognitive examinations regularly. They were recruited at the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center at Pennsylvania Hospital and all were allowed to keep their usual medications.

A total of 40 people without Parkinson’s, deemed cognitively fit and matched for the patients’ ages and education levels, were recruited from two elderly control research databases. These individuals were used as controls for this study, which was supported by the Smith Family Fund.

All 83 participants were randomly shown 10 high-resolution photographs of action (high-motion) paintings by the artist Jackson Pollock and neoplastic (low-motion) paintings by the artist Piet Mondrian.

Then, they were asked to rate each painting in nine categories: liking, beauty, interest, familiarity, motion, complexity, balance, color-hue, and color-saturation. These ratings were done using a 7-point Likert scale, in which a score of one meant a negative opinion and a score of seven reflected a positive opinion.

The color ratings were used as a relatively objective control.

Overall, the Parkinson’s patients preferred the paintings by Pollock while the healthy controls liked those of Mondrian. Perceptions of movement, however, were always significantly lower in Parkinson’s patients compared with the controls.

This was detected with both Pollock’s and Mondrian’s paintings, suggesting that the feeling of movement was not necessarily restricted to the strokes simulating bodily actions. Instead, according to the researchers, the findings showed that abstract visual elements in a painting can be viewed as dynamic and rhythmic.

“Our findings are particularly significant because, previously, it was posited that viewing abstract art stimulated the motor system because people could envision the gestures the artist took when painting,” said Stacey Humphries, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the neurology department and the study’s lead author.

“But our research shows that even without those representations of movement, the motor system can interpret static visual clues as movement and in turn impact the viewer’s aesthetic appreciation,” Humphries said.

No differences were seen between the two groups regarding the complexity ratings or the relationship between complexity and liking of art.

The researchers noted that the Mondrian paintings that were given the highest motion ratings in this study “contained more visual elements, overlapping lines, repetition, and many small areas of contrasting colors,” according to the press release.

The results suggest that “the brain’s motor system is involved in translating nonrepresentational information from static visual cues in the image into representations of movement,” the researchers wrote.

In addition, the findings support the idea that changes in the brain affect how art is perceived and likely valued.

Since the Parkinson’s patients were allowed to keep taking their regular medication — which most often includes dopaminergic medicines, specifically levodopa — how dopamine could affect their aesthetic experiences remains unknown.

Of note, Parkinson’s is characterized by the loss of neurons that make the neurotransmitter dopamine, a chemical messenger that allows nerve cells to communicate and, among other functions, helps regulate movement.

“Overall, we find support for hypotheses linking motion, motor responses, and aesthetic appreciation. People with Parkinson’s disease have altered art appreciation that is linked specifically to their altered ability to form movement representations from static abstract images,” the researchers concluded.