Low muscle mass is more common in early-stage Parkinson’s disease

Study finds higher odds of low muscle mass, especially in older men

Written by |

- Low muscle mass is common in Parkinson’s disease, especially in older men.

- It was linked to a slightly larger blood pressure drop shortly after standing.

- However, it wasn’t linked to more orthostatic symptoms like dizziness or lightheadedness.

Low muscle mass is more common in people with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease than in those without the condition, especially in older men, a study found. While it was linked to a slightly larger blood pressure drop shortly after standing, it was not linked to more orthostatic symptoms, such as dizziness or lightheadedness.

The findings come from the study, “Prevalence of low muscle mass and its association with orthostatic hypotension and related symptoms in Parkinson’s disease,” published in npj Parkinson’s Disease by researchers in South Korea.

Loss of muscle mass has been linked to problems with movement, balance, and blood pressure — issues that are common symptoms of Parkinson’s, a neurodegenerative disease caused by the loss of certain nerve cells in the brain. While muscle loss appears to be frequent in Parkinson’s, researchers are still working to understand how it relates to symptoms and day-to-day function.

Researchers examined low muscle mass rates

To estimate how common low muscle mass is, and how it relates to orthostatic hypotension, the researchers compared 409 people with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease with 2,045 people without the condition. The Parkinson’s group had an average age of 71.1 years and had lived with the disease for an average of 4.8 years. The groups were matched by age, sex, and height to help ensure the comparison wasn’t driven by body size differences or demographics.

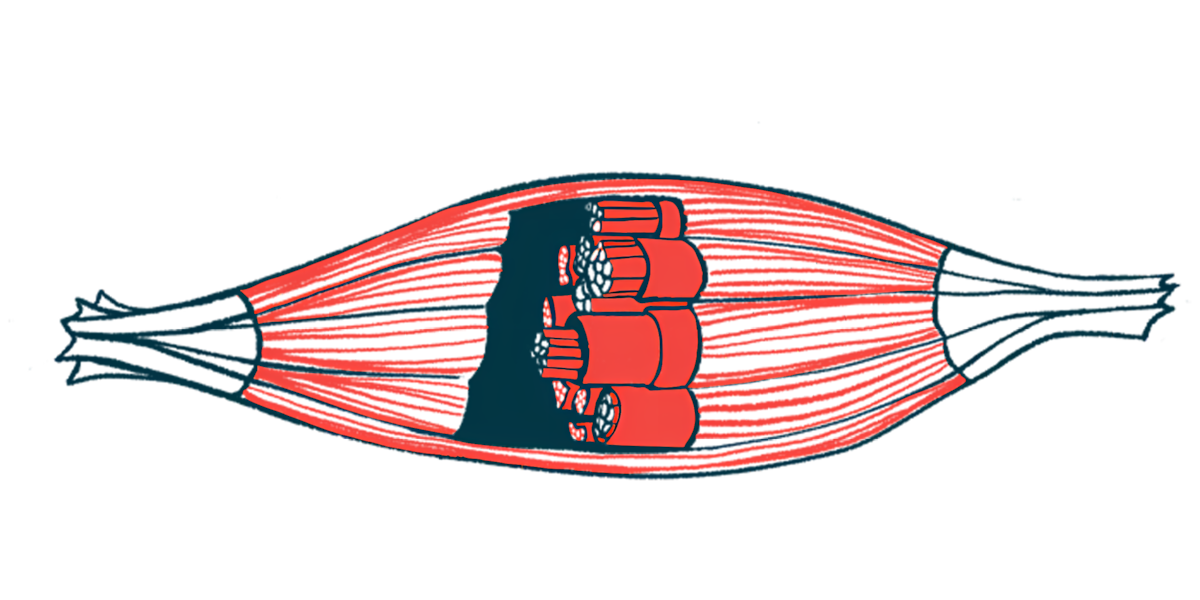

Low muscle mass was significantly more common in people with Parkinson’s than in those without the condition (35% vs. 24.8%). After accounting for age and sex, people with Parkinson’s had 62% higher odds of low muscle mass. The difference was most pronounced in men (43.9% vs. 29.6%) and in adults ages 70 years and older (45.1% vs. 29.9%) compared with younger adults (21.6% vs. 17.8%).

Low muscle mass was not linked to how long someone had Parkinson’s, symptom severity, or cognitive scores on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Researchers also found no significant difference in low muscle mass rates between women with Parkinson’s and women without the disease.

Researchers then measured blood pressure while participants were lying down and again after standing. Among 405 people with complete data, 141 had low muscle mass and 264 had normal muscle mass. Orthostatic hypotension was common in both groups (46.8% vs. 38.6%), with no significant difference between groups. The same pattern was seen when looking at both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Systolic blood pressure is measured when the heart beats and pushes blood into the arteries, and diastolic blood pressure is measured when the heart relaxes.

Low muscle mass tied to a slightly larger early BP drop after standing

However, when the researchers looked more closely at blood pressure changes over time, they found that people with low muscle mass had a slightly larger drop 30 seconds after standing, especially in diastolic blood pressure. This early change may suggest that muscle mass plays a small role in how quickly the body adjusts blood pressure after standing. Blood pressure at later time points, up to five minutes after standing, was similar between groups.

Overall, the study suggests that people with Parkinson’s disease, especially older men, are more likely to have low muscle mass. While low muscle mass was linked to a slightly larger blood pressure drop shortly after standing, it did not appear to increase orthostatic symptoms such as dizziness or lightheadedness.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine the association between muscle mass, [orthostatic hypotension], and its related symptoms in patients with [Parkinson’s],” the researchers wrote. However, “the clinical relevance of early [blood pressure] changes associated with [low muscle mass] remains uncertain,” so more studies are needed.