COVID-19 Infection May Raise Risk of Parkinson’s, Scientists Say

People who are infected with SARS-CoV2 — the virus that causes COVID-19 — may be at greater risk of later developing Parkinson’s disease, researchers suggest in a commentary.

In their commentary, “Is COVID-19 a perfect storm for Parkinson’s disease?” published in Trends in Neurosciences, the researchers reviewed three cases of Parkinson’s-like symptoms appearing in people within weeks of contracting COVID-19.

While these cases, and similar reports, do not prove a connection between COVID-19 and Parkinson’s, they highlight the need for detailed record-keeping to better understand whether a relationship exists and how it might form.

“As we continue to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic today, we also must consider its implications for the future,” Patrik Brundin, MD, PhD, a commentary author and Parkinson’s specialist with the Van Andel Institute in Michigan, said in a press release.

“COVID-19 is clearly a major and ongoing public health threat, but the consequences of infection may end up being with us for years and decades to come,” Brundin added.

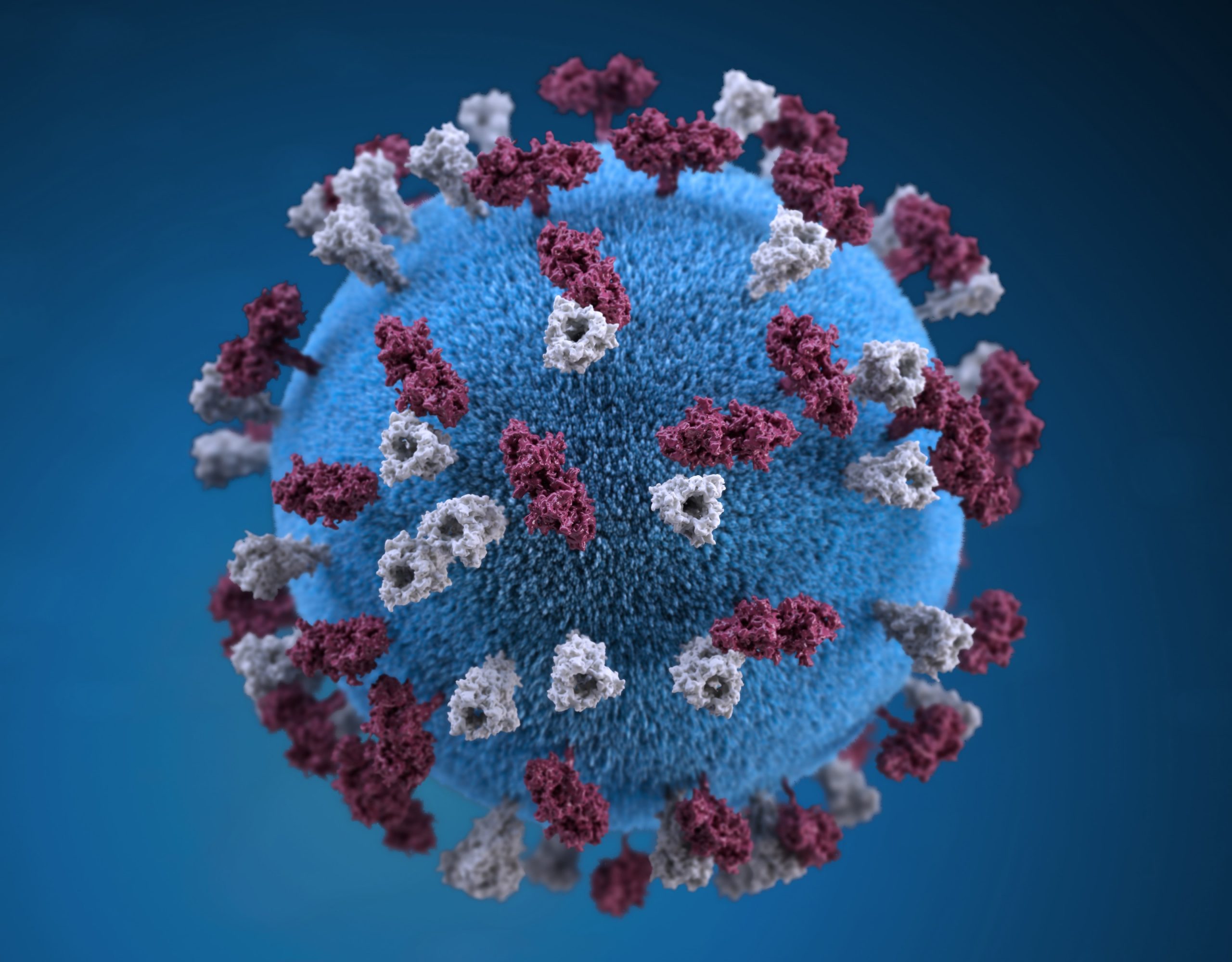

SARS-CoV2 was characterized less than a year ago, and researchers are still working to understand how this virus can affect the body, both in the short and long term.

Since the start of the pandemic, there have been three published cases of people — in Brazil, Israel, and Spain — who developed Parkinson’s-like symptoms shortly after becoming infected with SARS-CoV2. These patients, ages 35, 45 and 58, all had respiratory infection severe enough to require hospitalization.

None had a family history of Parkinson’s, or any early signs of the disease. Genetic testing performed on one patient identified no Parkinson’s-associated mutations.

In all three cases, brain imaging tests found evidence of reduced activity in a brain region where the dopamine, a chemical messenger that helps control movement, is produced — one of the hallmarks of Parkinson’s.

Two people were treated with medications that increase dopamine activity (e.g., levodopa), and responded to treatment. The remaining patient recovered without treatment.

The researchers emphasized that these individual cases cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship between COVID-19 and Parkinson’s.

“Possibly, the reported patients were destined to develop PD [Parkinson’s disease] and were on the cusp of losing the number of [dopamine-producing] neurons required for the emergence of motor symptoms, and the viral infection only accelerated an ongoing neurodegenerative process around a critical timepoint,” the researchers wrote.

“However, the rapid onset of severe motor symptoms in close temporal proximity to the viral infection is still suggestive of a causal link,” they added.

They also proposed three mechanisms by which COVID-19 might set the stage for Parkinson’s.

First, COVID-19 has been linked with blood clots and other problems with the circulatory system. It is possible that such problems may cause brain damage, possibly by affecting blood flow to certain parts of the brain. If this happens in brain regions where dopamine is produced, patients could develop symptoms similar to those of Parkinson’s.

Second, Parkinson’s has been associated with increased brain inflammation. Conceivably, the acute inflammation that results from viral infection could lead to brain inflammation similar to what occurs in the context of Parkinson’s.

“Evidence is mounting that the side effects of COVID-19 infection, such as inflammation and damage to the vascular system, could lay the foundation for development of Parkinson’s disease,” Brundin said.

Third, SARS-CoV2 may infect brain cells, and be a neurotropic virus. This hypothesis is backed up by studies reporting the virus has been detected in the brains of some people who died from COVID-19; other studies show dopamine-producing neurons contain high levels of the protein receptor that SARS-CoV2 uses to infect cells.

“SARS-CoV-2 is considered a respiratory virus, however, its virulence and pathogenic [disease-causing] potential particularly for neurological complications continues to surprise us. Some patients can develop severe neurological manifestations despite mild respiratory symptoms,” said Avindra Nath, MD, a co-author and infections specialist with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

It is possible that a brain infection could raise levels of the Parkinson’s-related protein alpha-synuclein, as has been observed in other viral brain infections, such as those caused by the West Nile virus.

“While acute parkinsonism in conjunction with COVID-19 appears to be rare, spread of SARS-CoV-2 widely in society might lead to a high proportion of people being predisposed to developing PD later in life,” the researchers concluded. “Therefore, it is important to carefully follow large cohorts of people affected by COVID-19, and monitor them for manifestations of PD.”