‘On Chip’ Blood-Brain Barrier Model Paves Way for Personalized Therapy, Study Suggests

Written by |

Shutterstock

Using stem cells, researchers have recreated the complexity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) — a critical protective brain structure — in a chip roughly the size of an AA battery.

This personalized BBB experimental model, which combines stem cell research with Emulate’s Organ-Chip technology, will allow scientists to better understand how the barrier works while also providing a novel way to investigate several human neurological diseases. By recreating true-to-life biology in a chip, researchers at Cedars-Sinai can assess tailored strategies for people affected by progressive brain disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.

The model was described in the study, “Human iPSC-Derived Blood-Brain Barrier Chips Enable Disease Modeling and Personalized Medicine Applications,” published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

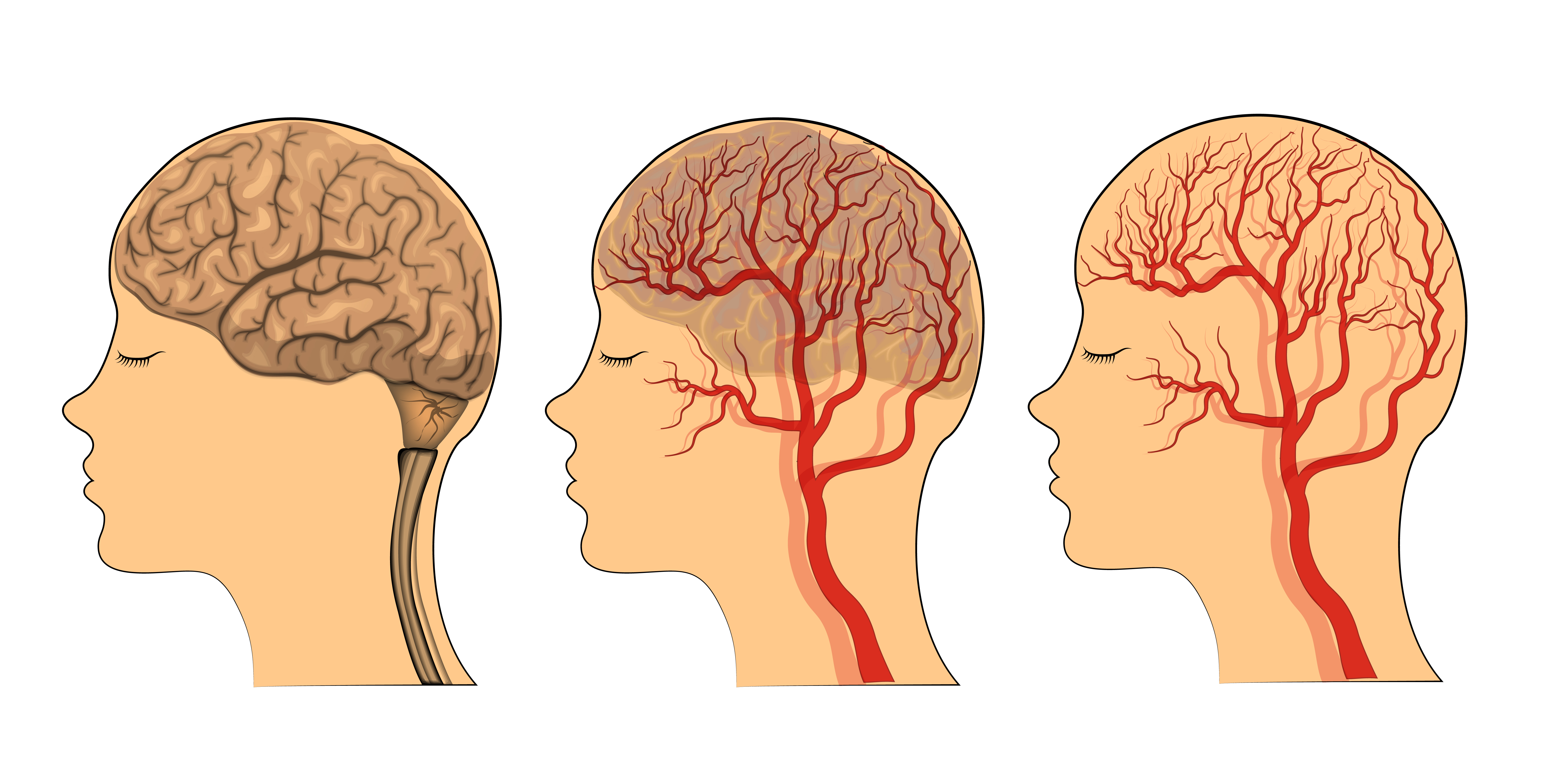

The BBB is a semipermeable membrane, made of a complex network of blood vessels, that works as a natural filter that selects what reaches the brain. It blocks toxins and other foreign substances that are in the bloodstream from entering brain tissue, and potentially damaging it.

However, the BBB also can prevent “good” chemical agents from entering and targeting the brain, creating a major barrier for the efficient delivery of therapeutics that need to reach the brain and central nervous system to work.

Given the BBB’s complexities, transposing it represents an important step for the development and efficacy of therapies targeting neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease.

Indeed, some studies have suggested that several human neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s, are linked to defects in the BBB that may prevent healthy and necessary natural molecules from reaching the brain. That, in turn, supports the progression of the disease, this research suggests.

To date, it remains very difficult to study and fully understand how the BBB works, and to address the extent of its involvement in neurological diseases.

Cedars-Sinai researchers developed an “on chip” model of the BBB that specifically mimics the behavior of the barrier’s blood vessels and their interaction with brain cells.

The team used inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from three healthy donors and one patient with Huntington’s disease to test their new experimental model. iPSCs are derived from either skin or blood cells that have been reprogrammed back into a stem cell-like state, which allows for the development of an unlimited source of any type of human cell needed for therapeutic purposes.

Using specific chemical stimulus, the researchers were able to transform iPSCs into mature BBB blood vessel cells or brain cells. The cells were then cultured on Emulate’s chip slide, which allowed a platform for cells to reconstitute the complex microenvironment of the brain and BBB.

The recreated BBB model was able to selectively allow the transport of some molecules from the BBB side across to the brain cells, confirming that it was working as as it naturally does in the body.

The model formed a functioning unit of a blood-brain barrier that mimicked what occurs in the body — including blocking the entry of certain drugs.

Researchers then created a model derived from cells from Huntington’s patients and people with Allan-Herndon-Dudley syndrome, a rare congenital neurological disorder. That barrier showed a different permeability pattern compared with the BBB model derived from healthy volunteers.

“Altogether, these results suggest that patient-specific iPSC-based BBB-Chips may be used to predict inter-patient variability in BBB functions,” the researcher said. They said the models also may help “predict human central nervous system drug penetrability.”

This BBB-chip model paves the way for a promising avenue for precision medicine, the investigators said.

“The possibility of using a patient-specific, multicellular model of a blood-brain barrier on a chip represents a new standard for developing predictive, personalized medicine,” Clive Svendsen, PhD, director of the Cedars-Sinai Board of Governors Regenerative Medicine Institute, and the study’s senior author, said in a press release.