Transplanted Nerve Cells in Brain of Parkinson’s Patient Seen to Survive, and Thrive, for Years

Written by |

Analysis of a Parkinson’s patient has yielded the first evidence that transplanted nerve cells can survive and function in diseased human brains for almost 25 years. The finding was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), in the study, “Extensive graft-derived dopaminergic innervation is maintained 24 years after transplantation in the degenerating parkinsonian brain.”

Pioneering transplants of nerve cells into the brains of Parkinson’s disease patients were carried out in the late 1980s and the 1990s by researchers at Lund University in Sweden. A fundamental question of concern to scientists since was whether the transplanted neurons could survive and establish neural connections in the host brain over time, despite the disease’s neurodegenerative progression.

Researchers, led by Anders Björklund, Olle Lindvall, and Jia-Yi Li, demonstrated that the transplanted cells could not only survive for decades, but also restore normal production of a neurotransmitter, called dopamine, in the transplanted region of the brain.

“Our findings show that transplanted nerve cells can survive and function for many years in the diseased human brain,” Professor Lindvall, a senior study author, said in a press release. “This is the first time a patient has shown such a well-functioning transplant so many years after transplantation of nerve cells to the brain. At the same time, we have observed that the transplant’s positive effects on this patient gradually disappeared as the disease spread to more structures in the brain.”

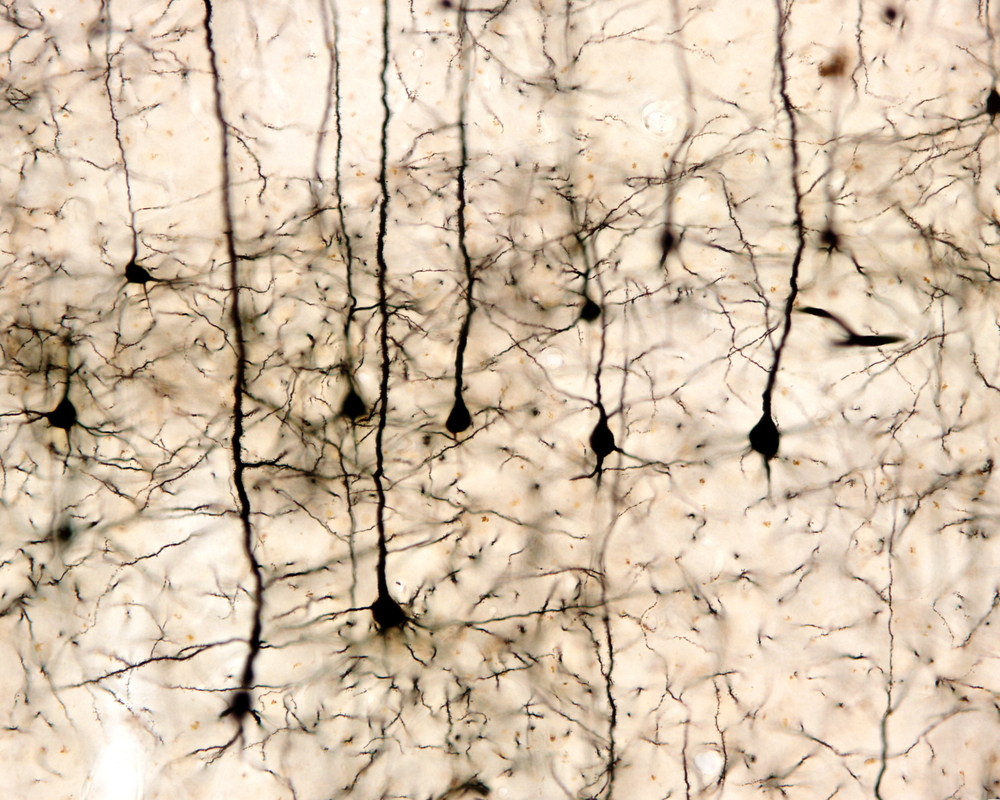

A Parkinson’s patient who underwent transplantation of dopamine-producing nerve cells 24 years prior to his death was analyzed by the research team. Three years after the transplant, the patient was already showing great improvement and no longer needed L-dopa medication. Ten years following the operation, brain-imaging technology showed a completely normal dopamine function. Now, after 24 years, analysis of the patient’s brain revealed that the dopamine-producing transplanted cells were still present and with normal neural connections.

“This study is completely unique,” said Professor Björklund. “No transplanted Parkinson’s patient has ever been followed so closely and over such a long period. The patient was also unique in the sense that the nerve cells were only transplanted to one hemisphere of the brain, which meant that the other, which did not receive any transplant, could function as a control. What we have learnt from the study of this patient will be of great value for future attempts to transplant dopamine-producing nerve cells obtained from stem cells, a new development led by researchers in Lund.”

Professor Li added, “This gives us a better understanding of how Parkinson’s disease spreads in the brain.”