Subtle Changes in Natural Oil of Skin May Mark Parkinson’s Onset

Written by |

Subtle changes in an oil naturally produced to protect the skin may announce whether or not you have Parkinson’s disease, according to a study in patients and other adults.

Scientists at the University of Manchester, building on previous work, discovered differences in the composition of sebum — the oily substance produced by sebaceous glands under the skin — between people with Parkinson’s and those without it.

If these findings are validated and further developed in future studies, sebum could provide a simple and non-invasive way to detect Parkinson’s in early stages, and possibly help in monitoring its progression.

The study, “Metabolomics of sebum reveals lipid dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease,” was published in Nature Communications.

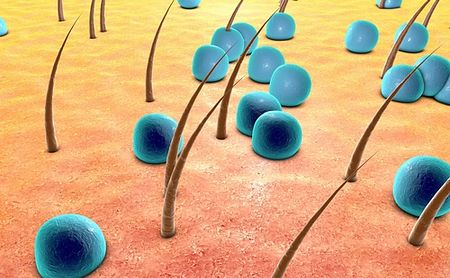

Sebum is a complex fat-rich substance that serves to protect the skin by, among other things, helping to regulate its temperature and mitigate damage from sun exposure.

But it’s produced in excess in Parkinson’s patients, and is the cause of their “oily skin,” and the itchy and scaly rash called seborrheic dermatitis that occurs in up to 60% of these people.

While sebum is often studied in dermatology, it has rarely been used for diagnosing a disease.

The Manchester team had previously identified several chemicals in sebum from Parkinson’s patients that one member described as smelling similar to Parkinson’s.

This member, a retired nurse named Joy Milne, is a known Parkinson’s “super smeller.” Years earlier, she had reported noticing changes in her husband’s smell some time before he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at age 45.

Milne’s description of a Parkinson’s aroma and the discovery of chemical differences in Parkinson’s-related sebum led Perdita Barran, PhD, and her associates to take a closer look at the biochemistry of skin oil.

“If we can define what is behind this Parkinson’s scent, perhaps we can develop objective tests to diagnose the disease earlier,” said Barran, in a press release from The Michael J. Fox Foundation, which with Parkinson’s UK supported the study.

“Measuring Parkinson’s disease with such an easy-to-obtain sample, a swab of skin secretions, would also allow for more widespread screening,” she added.

The researchers recruited 274 people to their study: 138 Parkinson’s patients taking disease-relevant medications, 80 “drug naïve” patients (no such medications), and 56 healthy adults as a control group. Sebum samples were collected through gauze swabbing of the skin of participants’ upper back.

Patients showed several marked differences in sebum composition relative to controls. But little difference was seen between patients based on their treatment status.

This suggested that the chemicals found in sebum were representative of the disorder itself, and not associated with dopaminergic medication.

Researchers noted that there was not enough clinical data “to hypothesise on the ability of a sebum analysis to help stratify disease progression, although it should be included in further studies.”

The greatest differences occurred in fat metabolism related to the carnitine shuttle, sphingolipids, arachidonic acid, and fatty acid biosynthesis.

The carnitine shuttle is a pathway for transporting long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) to mitochondria in cells, where they are converted to energy. Poorer mitochondrial metabolism of LCFAs is seen as a potential Parkinson’s biomarker, and dysregulation of the carnitine shuttle has been documented in frail, elderly people.

Disruptions to sphingolipid biology are implicated in defects in mitochondrial and lysosomal metabolism, both of which play roles in Parkinson’s. Higher alpha-synuclein levels, a hallmark of Parkinson’s, is also known to alter sphingolipid metabolism.

Ceramides, a type of sphingolipid, are directly linked to cholesterol production. Cholesterol, in turn, feeds into the steroid hormone production pathway, which is the most significantly altered pathway among medicated Parkinson’s patients.

Overall, the study succeeded in identifying differences between people with and without Parkinson’s using a simple skin swab. Although the team did not find enough data to support the use of this test in tracking disease progression, they wrote that this should be investigated in future studies.

“This study,” the researchers concluded, “shows sebum can be used to identify potential biomarkers for [Parkinson’s].”