MRI Scans That Capture Parkinson’s Progression May Aid in Research

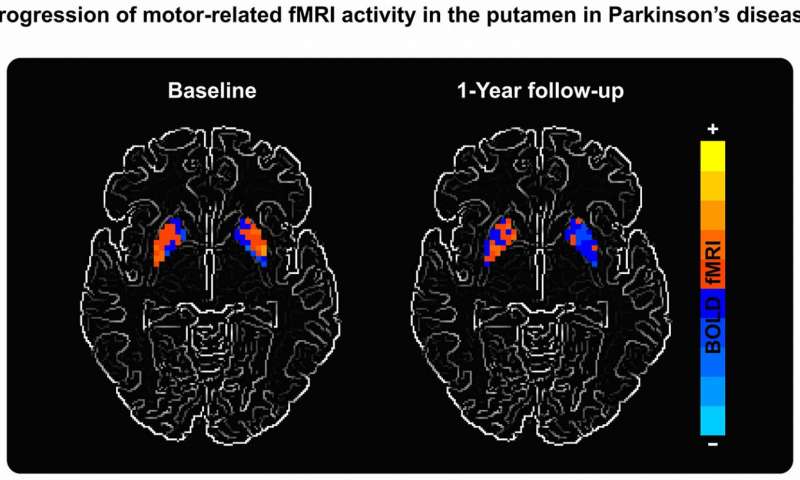

A scan of Parkinson's patient and UF study participant, with high activity areas (orange) at baseline, and low-activity (blue) one year later. (Credit: David Vaillancourt, UF)

Researchers at the University of Florida have developed a non-invasive way of following disease progression in Parkinson’s, and its related conditions, that uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The method is expected to soon be used in a clinical trial, and appears to be a way of evaluating the efficacy of experimental treatments to slow or halt disease progression in patients.

Their study, “Functional MRI of disease progression in Parkinson disease and atypical parkinsonian syndromes,” published in Neurology.

To facilitate the development of therapies that may slow Parkinson’s progression, researchers need to understand functional changes taking place in the brain. Previous studies have used drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier to assess neurological changes in patients. Now, researchers led by David Vaillancourt, PhD, a professor in UF’s Department of Applied Physiology and Kinesiology, have come up with a way of using a functional MRI scan to track disease progression.

“Our technique does not rely upon the injection of a drug. Not only is it non-invasive, it’s much less expensive,” said Vaillancourt in a press release.

The study enrolled 46 Parkinson’s patients, 13 people with multiple system atrophy (MSA), 19 with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and 34 healthy controls. Researchers asked participants to engage into specific motor tasks while they used functional MRI to examine five brain areas critical for movement and balance. All participants were evaluated at the study’s start (baseline) and one year later.

Results showed that while healthy controls had no changes in brain activity, patients with Parkinson’s had evidence of deterioration in two examined areas at the one-year mark. Those with MSA had deterioration in three areas, and PSP patients showed deterioration in all five areas.

“For decades, the field has been searching for an effective biomarker for Parkinson’s disease,” said Debra Babcock, MD, PhD, program director at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “This study is an example of how brain imaging biomarkers can be used to monitor the progression of Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders.”

An NIH-funded study set to begin in November will use this approach, along with a biomarker identified by the research team in 2015 that uses MRI to detect increases in unconstrained fluid — a mark of disease progression — in the substania nigra of the brain. The study will test whether a drug approved for symptom relief in Parkinson’s can slow neurological degeneration.

Identifying biomarkers is “an essential part of moving towards the development of treatments that impact the causes, and not just the symptoms, of Parkinson’s disease,” said Katrina Gwinn, MD, also a program director at the NIH institute.